Is there enough information?

a , b , and c are real constants such that there exists exactly one square whose four vertices lie on the cubic curve y = x 3 + a x 2 + b x + c .

What is the area of this square (to 3 decimal places)?

The answer is 8.485.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

3 solutions

This solution is almost isomorphic to my solution over here . I didn't finish mine though. :P

You have shown that if we have an inscribed square, p ( x ) has roots at − r , − s , 0 , s , r , but how do you know that p ( x ) will have only these roots? In other words, if we had 2 sets of 4 roots (plus a root at 0), how would that imply that there were 2 inscribed squares?

Using symmetry around origin the cubic curve is taken as

y=x^3-gx, where g is to be found?

The coordinates of four vertices of inscribed square are assumed as (a,b), (b,-a),(-a,-b) and (b,-a). The area of square as 2(a^2+b^2) is to be answered?

Substituting vertices values in cubic curve equation and carrying out algebra for finding unique square, we get the following results:

g=√8,. b=√c, a=-b^3+gb,

Where, c is given by :

c^4-(3g)c^3+3(g^2)c^2-g(g^2+1)c+(g^2+1)=0, solving get,

c=(1/2)(3√2+√6) and

area of square = 2(a^2+b^2)=6√2,

Answer=6√2=8.48528

improve more

Here's a very classical and formal approach... and also much more brutish.

First, all cubic curves have a centre of symmetry, in this case it is ( − 3 a , 2 7 2 a 3 − 3 a c + c ) . Let's center the curve on the origin: f ( x ) : = x 3 + a x 2 + b x + c becomes g ( x ) = x 3 + p x with g ( x ) : = f ( x − 3 a ) + C , where C and p are real constants.

Second, let's prove the square we're looking for is centered on the centre of symmetry of the curve, i.e. the origin. If it weren't, using central symmetry, there would be another square of same size and orientation, centered on the point opposed to the first center. Therefore, to ensure uniqueness, the square must be centered on the origin.

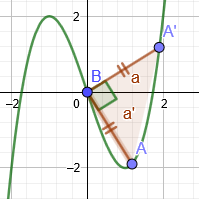

This makes the work much simpler, since we're now looking for a pair points on the curve which are 90° away from each other and equally distant from the origin.

Moreover, since the square is centered on the origin, each one of its vertices occupies a different quadrant. Therefore p < 0 (else g would be an increasing function and since g ( 0 ) = 0 , its curve would never reach the lower right nor the upper left quadrants).

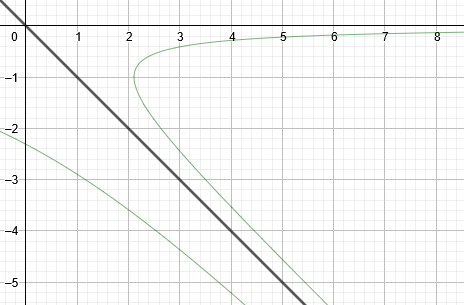

The following graph sums up the simplified problem.

Warning: heavy algebra/calculus below.

Let's call ( x 1 , y 1 ) the coordinates of point A , first corner of the square and likewise, x 2 , y 2 for point A ′ . A 90° rotation centered on the origin applied to A yields ( x 2 , y 2 ) = ( − y 1 , x 1 ) and since both A and A ′ are on the curve of equation y = g ( x ) , { x 2 = − x 1 3 − p x 1 x 1 = x 2 3 + p x 2 Substituting x 2 in the second line yields x 1 + ( x 1 3 + p x 1 ) 3 + p ( x 1 3 + p x 1 ) = 0 and after expanding and rearranging terms, the main equation is x 1 ( x 1 8 + 3 p x 1 6 + 3 p 2 x 1 4 + p ( p 2 + 1 ) x 1 2 + p 2 + 1 ) = 0 ( 1 )

Now let be ϕ ( t ) : = t 4 + 3 p t 3 + 3 p 2 t 2 + p ( p 2 + 1 ) t + p 2 + 1 ϕ ′ ( t ) = 4 t 3 + 9 p t 2 + 6 p 2 t + p ( p 2 + 1 ) ϕ ′ ′ ( t ) = 1 2 t 2 + 1 8 p t + 6 p 2

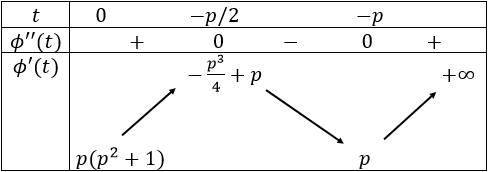

We're looking for a specific value of p such that there are exactly two solutions (they can't be equal as they're also abscissae of points on a curve of a function) to the equation ϕ ( t ) = 0 , since both correspond to the square of a corner's abscissa. A little basic analysis grants the following table of signs and variations. We're only studying ϕ and its derivatives over R + as ( 1 ) ⟺ x 1 ϕ ( x 1 2 ) = 0 .

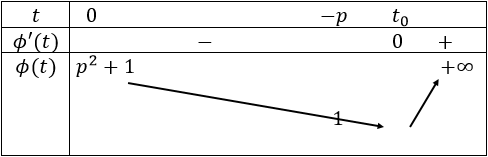

There are now two cases. If − 4 p 3 + p ≤ 0 i.e. p ≥ − 2 (reminder: p < 0 ), then calling t 0 the unique zero of ϕ ′ ,

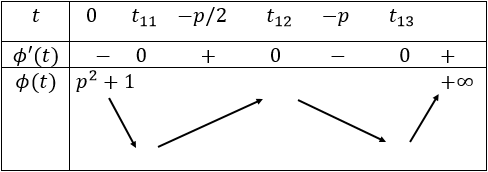

Else, p < − 2 and, calling 0 < t 1 1 < t 1 2 < t 1 3 the zeros of ϕ ′ ,

To determine the values of ϕ (or at least their sign) at the zeros of its derivative, let's interpolate it. We know, since t 1 (equally referring to any zero of ϕ ′ ) that ϕ ′ ( t 1 ) = 4 t 1 3 + 9 p t 1 2 + 6 p 2 t 1 + p ( p 2 + 1 ) = 0 ( 2 ) Substracting 4 t 1 ⋅ ( 2 ) and then 4 p ⋅ ( 2 ) to 1 6 ϕ ( t 1 ) yields 1 6 ϕ ( t 1 ) = 1 6 t 1 4 + 4 8 p t 1 3 + 4 8 p 2 t 1 2 + 1 6 ( p 3 + p ) t 1 + 1 6 ( p 2 + 1 ) = 1 2 p t 1 3 + 2 4 p 2 t 1 2 + 1 2 ( p 3 + p ) t 1 + 1 6 ( p 2 + 1 ) = − 3 p 2 t 1 2 + 6 ( − p 3 + 2 p ) t 1 + ( 1 6 − 3 p 2 ) ( p 2 + 1 )

Let be ψ ( s ) = − 3 p 2 s 2 + 6 ( − p 3 + 2 p ) s + ( 1 6 − 3 p 2 ) ( p 2 + 1 ) our interpolating function. It is a parabola whose abscissa of symmetry is − 2 ( − 3 p 2 ) 6 ( − p 3 + 2 p ) = p 2 − p .

Note: from this point, the solution isn't correct anymore, I am currently working on it

- If p < − 2 ,in order to have a unique zero of ϕ over R + , ϕ ( t 1 3 ) > 0 and ϕ ( t 1 1 ) = 0 , or, ϕ ( t 1 1 ) > 0 and ϕ ( t 1 3 ) = 0 .

- Else, the only possibility for a unique zero of ϕ over R + is ϕ ( t 0 ) = 0 , but we'll see later this impossible case.

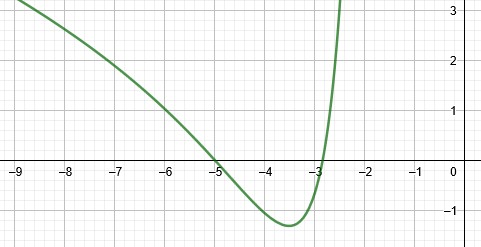

Solving zeros for ψ is much more easier than for ϕ , and at this point I started using CAS software. Plotting the curve defined by ψ ( s ) = 0 , with s as abscissa and p as ordinate gives (the black straight line has equation s = − p )

ψ has two zeros, their values are − p + p 2 ( 1 ± 3 p 2 + 3 8 ) , and both are on a different side of the s = − p curve.

- If ϕ ( t 1 1 ) = 0 , then also ψ ( t 1 1 ) =0, and then t 1 1 = − p + p 2 ( 1 + 3 p 2 + 3 8 ) since t 1 1 < − p / 2 < − p . Putting it back into ϕ , we get ϕ ( t 1 1 ) = − 2 7 p 4 ( 6 p 4 − 1 6 8 p 2 + 9 6 0 ) 3 ( p 2 + 2 8 ) − 3 0 p 4 + 1 3 4 4 p 2 − 8 8 3 2 = 0

Putting it back into ϕ , we get ϕ ( t 1 3 ) = 2 7 p 4 ( 6 p 4 − 1 6 8 p 2 + 9 6 0 ) 3 ( p 2 + 2 8 ) + 3 0 p 4 − 1 3 4 4 p 2 + 8 8 3 2 = 0

and the only solution for real negative p is p = − 2 2 . Thanks Wolfram Alpha, but don't you dare tell me the way!.

Now, numerically solving for p shows two solutions, − 2 2 and − 4 3 2 + 7 .

From the disjunction on the value of p , the variable t 1 3 could have been replaced by t 0 without changing any calculation. Therefore, the case p ≥ − 2 is impossible, leaving only p < − 2 valid. However, this won't be useful later on.

- If p = − 2 2 then the area of the square is through the Pythagorean theorem 2 ( x 1 2 + g ( x 1 ) 2 ) = 2 ( x 1 6 + 2 p x 1 4 + ( 1 + p 2 ) x 1 2 ) = 6 2 .

- Else, p = − 4 3 2 + 7 , and we lose t 1 3 > − p since t 1 3 = 3 ( 2 + 7 ) and t 1 3 + p = − 3 3 ( 2 + 7 ) < 0 .

Finally, p = − 2 2 and the answer is 6 2 ≈ 8 . 4 8 5 2 8 .

Congratulations if you thoroughly read this!

Suppose w.l.o.g that the centre of the square is at the origin. This means that if we rotate the curve by 9 0 ∘ or 1 8 0 ∘ , it will still pass through all four points of the square.

We denote the graph y = f ( x ) = x 3 + a x 2 + b x + c by γ and the vertices of the square A , B , C , D in that order.

Rotating this graph 1 8 0 ∘ we get the new graph γ which is y = x 3 − a x 2 + b x − c (this can be found from the equation − y = f ( − x ) ). Clearly, both graphs pass through A , B , C , D .

Then 2 a x 2 + 2 c = 0 has at least four different roots, implying that a = c = 0 . Now, when x = 0 , f ( x ) = 0 so the graph γ also passes through the origin. Since the curve must intersect all quadrants, we have b < 0 .

Now we rotate the graph γ by 9 0 ∘ , which gives rise to a graph with equation − x = f ( y ) . Call this graph γ ′ .

Then the intersection points of the two curves γ and γ ′ are determined by − x = f ( f ( x ) ) , and so are the roots to the polynomial p ( x ) = f ( f ( x ) ) + x . This polynomial has a degree of nine, since we are cubing a cubic expression.

It is easy to see, after a little experimentation, that these cubic graphs generally cross each other an even number of times in each quadrant. Since A B C D is the only square lying on the intersection of γ and γ ′ , the intersection points A , B , C , D must be double. Therefore, we can write p ( x ) as x [ ( x − r ) ( x + r ) ( x − s ) ( x + s ) ] 2 , where r and s are the x-coordinates of A and B . Since p ( x ) can also be written as ( x 3 + b x ) 3 + b ( x 3 + b x ) + x , we can equate coefficients to give the following equations-

3 b = − 2 ( r 2 + s 2 ) 3 b 2 = ( r 2 + s 2 ) 2 + 2 r 2 s 2 b ( b 2 + 1 ) = − 2 r 2 s 2 ( r 2 + s 2 ) b 2 + 1 = r 4 s 4

Solving these equations gives r 2 + s 2 = 1 8 . Since this is the square of half the length of the diagonal of A B C D , the area of the square is 2 × 1 8 = 7 2 . (this can easily be shown using a little algebra).