Congruency grows complex

If you consider the Gaussian integers Z [ i ] modulo 2 + i , how many congruency classes are there?

Clarifications :

-

Gaussian integers are of the form a + b i where a and b are integers.

-

z 1 ≡ z 2 ( m o d 2 + i ) means that z 1 − z 2 = ( 2 + i ) w for some Gaussian integer w .

Bonus Question : How many of the congruency classes are units, meaning that they have a multiplicative inverse?

The answer is 5.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

3 solutions

Moderator note:

Great explanation! Most people think that the conjugacy classes are up to z 1 − z 2 = a ( 2 + i ) .

Nice method. The Pick's Theorem argument is a bit harder when a , b are not coprime. If the fundamental square has B edge vertices (in Pick's sense), then we need precisely 1 + 2 1 ( B − 4 ) = 2 1 B − 1 of them to get all congruence classes (exactly one of the four corners of the square, and precisely half the others). So with I internal vertices, we have I + 2 1 B − 1 = A = a 2 + b 2 congruence classes.

Since N ( 2 + i ) = ∣ 2 + i ∣ 2 = 5 is prime, 2 + i is an irreducible element in the Euclidean domain Z [ i ] . Thus the ideal ⟨ 2 + i ⟩ is a prime, so maximal, ideal in Z [ i ] , and hence the quotient ring Z [ i ] / ⟨ 2 + i ⟩ is a field.

Since a + b i = ( a − 2 b ) + b ( 2 + i ) for any a , b ∈ Z , we deduce that every Gaussian integer is congruent to a real integer in this field, so that Z [ i ] / ⟨ 2 + i ⟩ = { a + ⟨ 2 + i ⟩ ∣ ∣ a ∈ Z } . Since, moreover, 5 = ( 2 + i ) ( 2 − i ) , we see that 5 ≡ 0 , and hence that Z [ i ] / ⟨ 2 + i ⟩ = { a + ⟨ 2 + i ⟩ ∣ ∣ a = 0 , 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 } . If 0 ≤ a ≤ b ≤ 4 were such that a ≡ b , then b − a = ( 2 + i ) w for some Gaussian integer w , and hence ( b − a ) 2 = N ( b − a ) = 5 N ( w ) is an ordinary multiple of 5 . Since 1 2 , 2 2 , 3 2 , 4 2 are not multiples of 5 , we deduce that a = b . Thus the congruence classes a + ⟨ 2 + i ⟩ , for a = 0 , 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , are distinct, and hence the field Z [ i ] / ⟨ 2 + i ⟩ contains 5 elements.

Since Z [ i ] / ⟨ 2 + i ⟩ is a field, all but one (namely 4 ) of the congruence classes are units. The congruence classes of 2 and 3 are mutual inverses, and the congruence classes of 1 and 4 are self-inverse.

Another careful solution! (+1)

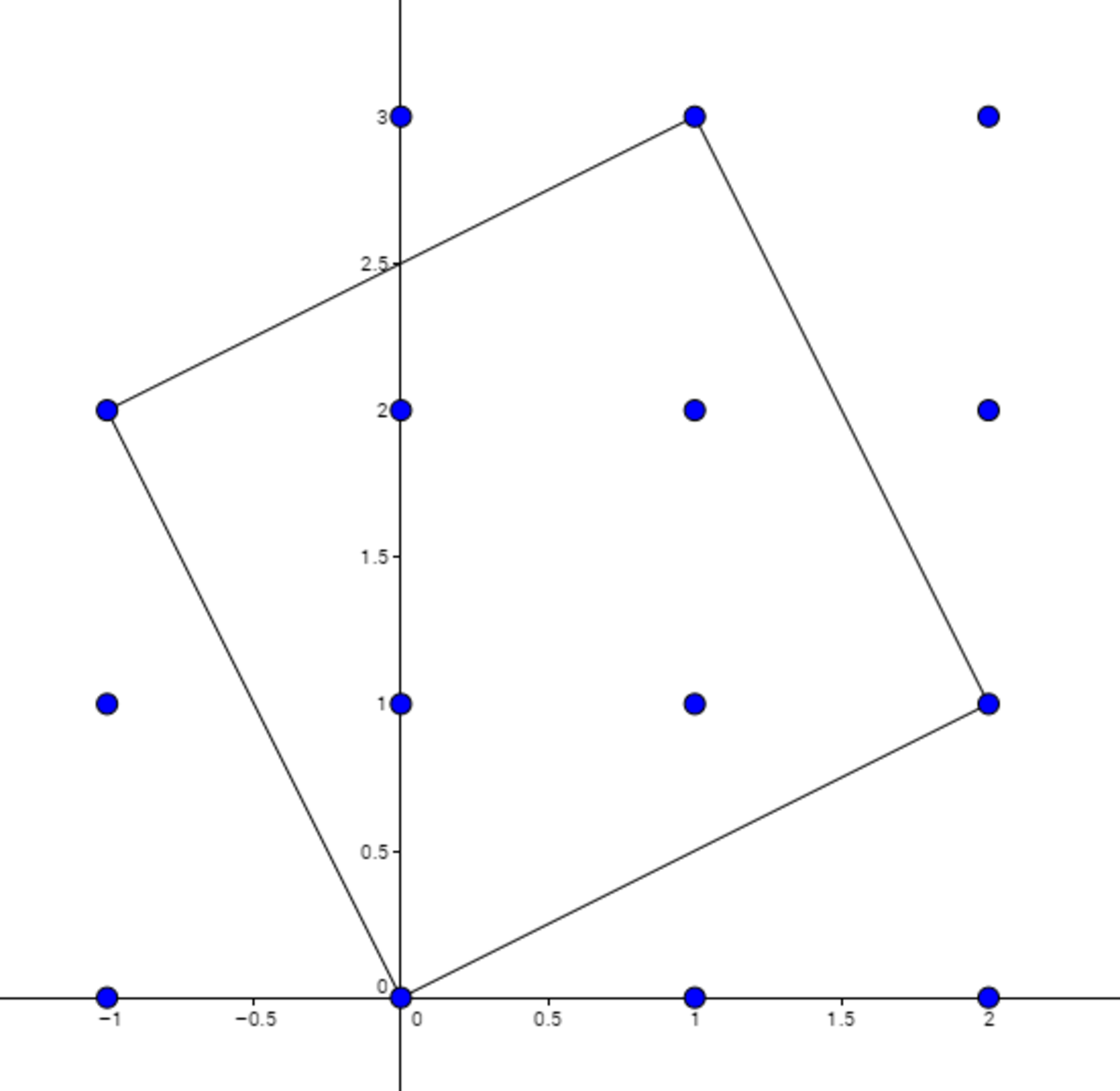

My approach is graphical:

First I think of a line passing

0

and

2

+

i

Then I remember that

i

, which is a Gaussian Integer, somehow 'represents' a rotation of

9

0

degrees.

So I draw a line passing

0

and

−

1

+

2

i

Then I finish the square:

So there are

5

congruency classes: the

4

points inside, and

1

vertex of the square.

Yes, this is a great illustration to the solution, showing a fundamental domain. (+1) I'm taking the liberty of referring to your solution in mine.

We observe that z 1 ≡ z 2 ( m o d 2 + i ) if z 1 − z 2 = ( 2 + i ) ( a + b i ) = a ( 2 + i ) + b ( − 1 + 2 i ) , meaning that z 1 − z 2 is an integer linear combination of 2 + i and − 1 + 2 i . Consider the lattice spanned by 2 + i and − 1 + 2 i ; as a fundamental domain, choose the square with its vertices at 0 , 2 + i , − 1 + 2 i , and 1 + 3 i . As representatives of our congruency classes, we can choose the four points in this fundamental domain, i , 2 i , 1 + i and 1 + 2 i and add one of the vertices of the square, 0, say, for a total of 5 classes.

See the excellent figure in 展豪 張's solution.

(We could use Pick's Theorem to count the points in the fundamental domain without actually finding them.)

This approach shows, more generally, that there are a 2 + b 2 congruency classes modulo a + b i .