78 of 100: Visualizing Algebra

What equation does this image correspond to?

The same setup can also be used to give a general formula using n .

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

14 solutions

I didn't understand the question but thanks to your answer I do now.

Venkatachalam, how did you construct this solution/these pictures? It is a very neat and simple way to explain it. :-)

Same here, I wasn't sure what the question meant..thanks

Wow Very simple and good Clap Clap Clap Clap

If the given image makes you trouble , first thing you may want to do is check the correctitude of the given equations.(A wrong equation can't be represented by using a shape like the given one.) well, 1st equation is false because the exponents are different,2nd equation must be checked and the 3rd is the only one that is true for every n. Well, the 3rd ecuation is matching the given shape.

This is how I solved it, but I don't get the image at all. It's just confusing to me :(

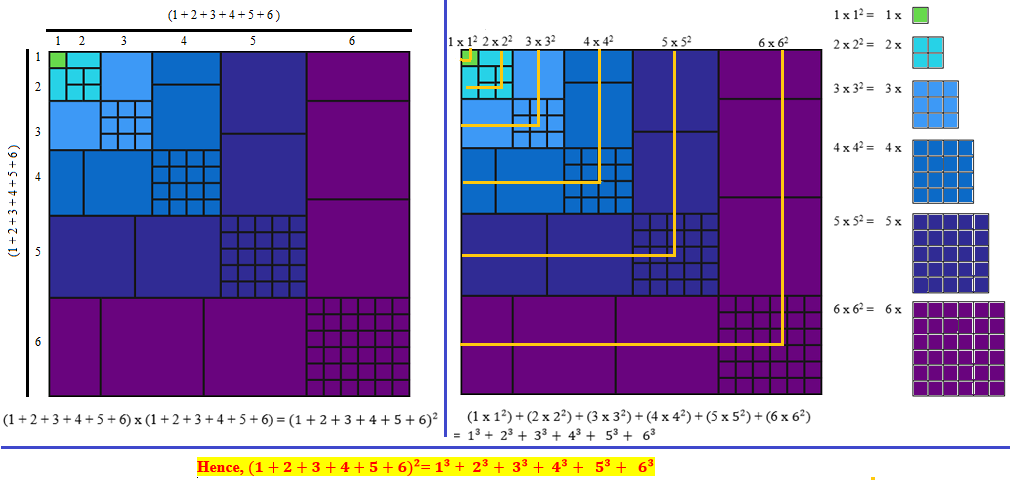

Look at each color: if you put together the pieces, you can create 1 square of side 1 (=1^3), 2 squares of side 2 (=2x2^2=2^3), 3 squares of side 3 (=3^3), 4 squares of side 4 (=4^3) and so on, where between the brackets I pointed out the area of that shape. The sum of all those squares makes one big square of side 1+2+3+4+5+6, thus proving that 1^3+2^3+3^3+4^3+5^3+6^3 = (1+2+3+4+5+6)^3. You can add squares of side 7,8,9,10... to the figure and demonstrate this property for a generic n

This is how I solved it. The first equation is obviously wrong because x^3 > x^2 for x >1. The second equation is slightly less obviously wrong. But clearly if you expand the exponentiation, you'll get the x^3 terms as well as a bunch of terms that look like x^2*y or xyz, so that's also not an equality. That leaves only one equation that could possibly be true.

We know that the square can be written as a sum of cubes 1 3 + 2 3 + 3 3 + 4 3 + 5 3 + 6 3 .

However, we see that these cubes also form a square, with sides 1 to 6. Thus, we know that 1 3 + 2 3 + 3 3 + 4 3 + 5 3 + 6 3 = ( 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 ) 2

Or, we could see that the first and second choices are obviously wrong: 1 ) The squares can never add up to the cubes of 1 through 6 ( 1 2 = 1 3 , but from 2 − 6 , the number cubed is larger than the square.) And 2 ): ( 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 = 2 1 ) 3 , is obviously larger than the cubes.

If you're having trouble seeing how this picture represents the two sides of the equation, the following two more detailed images may help: (1) Animated , (2) Non-animated

If you have Lego or snap cubes available, with a little practice, you can go from the square-of-sum layout to a sum-of-cubes in just a few seconds - as in the animated image. I recommend doing only five terms at most, though. Six is a little unwieldy.

To generalize, we could, for example, think of the dimensions of the purple square as n × n . Its area is, obviously, n 2 . Now we look at the dimensions of the two purple rectangular strips adjacent to the purple square. Their width is obviously n , and their length is equal to the sum of the first n − 1 integers, which is 2 n ( n − 1 ) , or 2 n 2 − n . The area of each rectangular strip is thus 2 n ( n 2 − n ) , or 2 n 3 − n 2 . Since there are two strips, their total area is n 3 − n 2 , so that when we add the area of the square, the area of the whole purple L-shaped region is exactly n 3 . This method could be used for any of the L-shaped regions, so we can see that they represent the successive integer cubes. The side of the entire square is obviously equal to the sum of the first n integers, or 1 + 2 + . . . + n − 1 + n , and its area is thus equal to ( 1 + 2 + . . . + n − 1 + n ) 2 This shows that ( 1 + 2 + . . . + n − 1 + n ) 2 = 1 3 + 2 3 + . . . + ( n − 1 ) 3 + n 3

Just consider the truthiness of each statement. 1 can’t be true, since the higher exponent means RHS > LHS. 2 also is not true as RHS > LHS. This is because the expansion of the RHS would contain all terms in the LHS, as well as many more other positive terms. Thus, equation 3 is the only valid equation.

Honestly, I just looked at the right to see which equation made sense, as that would be the answer.

Only the last one was correct, so there we go.

The image for this task is fascinating. It certainly can inspire great thinking.

To support this image in a multiple choice task, I would use ( 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 ) 2 as the common distractor expression because it is easier to discern in the image. Finding its equivalent 1 3 + 2 3 + 3 3 + 4 3 + 5 3 + 6 3 would be more compelling to me ...

My proof of the equivalence in this task uses the binomial square formula: ( a + b ) 2 = a 2 + 2 a b + b 2 and the trivial identity 1 n = 1 .

Eq. 1) First, it is obvious that 1 2 = 1 3 .

Eq.2) Now, consider ( 1 + 2 ) 2 = 1 2 + 2 ⋅ 1 ⋅ 2 + 2 2 .

Since 1 2 = 1 3 , the right-hand side of equation 2 is equivalent to 1 3 + 2 ⋅ 2 2 which is equivalent to 1 3 + 2 3 .

2 2 is evident (along the diagonal) in the task image and 2 ⋅ 1 ⋅ 2 may be sussed out from the image as the rectangles adjacent to 2 2 .

Eq. 3) Next consider ( 1 + 2 + 3 ) 2 = ( ( 1 + 2 ) + 3 ) 2 = ( 1 + 2 ) 2 + 2 ⋅ ( 1 + 2 ) ⋅ 3 + 3 2 .

In the right-hand side of equation 3, we've already seen the equivalence ( 1 + 2 ) 2 = 1 3 + 2 3 .

What's new here is 2 ⋅ ( 1 + 2 ) ⋅ 3 + 3 2 or 2 ⋅ 3 ⋅ 3 + 3 2 , which is 2 ⋅ 3 2 + 3 2 = 3 ⋅ 3 2 = 3 3 .

3 2 is evident (along the diagonal) in the task image and 2 ⋅ 3 ⋅ 3 may be sussed out as the two squares adjacent to 3 2 .

Eq. 4) Next consider ( 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 ) 2 = ( ( 1 + 2 + 3 ) + 4 ) 2 = ( 1 + 2 + 3 ) 2 + 2 ⋅ ( 1 + 2 + 3 ) ⋅ 4 + 4 2 .

In the right-hand side of equation 4, we've already seen the equivalence ( 1 + 2 + 3 ) 2 = 1 3 + 2 3 + 3 3 .

What's new here is 2 ⋅ ( 1 + 2 + 3 ) ⋅ 4 + 4 2 .

A few equivalences are needed here to show that what's new in equation 4 is 4 3 .

Mathematically, 2 ⋅ ( 1 + 2 + 3 ) ⋅ 4 + 4 2 = 2 ⋅ ( ( 1 + 2 ) + 3 ) ⋅ 4 + 4 2 = 2 ⋅ ( 3 + 3 ) ⋅ 4 + 4 2 = 2 ⋅ ( 2 ⋅ 3 ) ⋅ 4 + 4 2 = 3 ⋅ 4 2 + 4 2 = 4 ⋅ 4 2 = 4 3 .

Other equivalences will show that what's new in equation 4 is shown in the task image as squares and rectangles adjacent to 4 2 .

2 ⋅ ( 1 + 2 + 3 ) ⋅ 4 + 4 2 = 2 ⋅ ( 2 + 4 ) ⋅ 4 + 4 2 = 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 4 + 2 ⋅ 4 ⋅ 4 + 4 2 .

4 2 is evident (along the diagonal) in the task image and 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 4 + 2 ⋅ 4 ⋅ 4 may be sussed out as the rectangles and squares adjacent to 4 2 .

Expansion of ( 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + . . . + n ) 2 , as I've shown above, will result in two types of formulae:

For odd n, ( 1 + 2 + . . . + n ) 2 = 1 3 + 2 3 + . . . + ( n − 1 ) ⋅ n 2 + n 2 , where the n-terms are equivalent to n 3 .

For even n, ( 1 + 2 + 3 + . . . + n ) 2 = 1 3 + 2 3 + 3 3 + . . . + ( n − 2 ) ⋅ n 2 + 2 ⋅ 2 n ⋅ n + n 2 , where the n-terms are equivalent to n 3 .

You do not even have to look at the image. Check the validity of each of the equations, and choose the one which is a true equation.

!^3 + 2^3 + ........ + n^3 = [n(n + 1/2]^2 = (1 + 2 + 3 + ..... + n)^2, so the correct answer is the third one.

The first two "equations" are actually, and fairly obviously, false. One wonders what sort of legitimate picture can be rendered for them? That only leaves the third which happens to be the summation formula for the sum of cubes of consecutive integers starting from 1. That formula has the charming and curious property of being the square of the sum of positive integers (exponent of 1) as depicted in the diagram. We see in the picture that each successive large square has side length equal to the sum of the preceding integers. Consequently its area will be the square of that sum, the sum of the cubes of the same integers, and each added area is equal to the cube of the corresponding integer.

Since the first two equations cannot hold, the third equation is the only option. Checking both hand sides shows this equation is the only one that holds.

1 3 + 2 3 + 3 3 + 4 3 + 5 3 + 6 3 = 1 2 + 2 2 + 3 2 + 4 2 + 5 2 + 6 2 is obviously false. If you think about for a single second, you know that this equation is false.

1 3 + 2 3 + 3 3 + 4 3 + 5 3 + 6 3 = ( 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 ) 3 is also false. This is because ( a + b ) 3 is NOT equal to a 3 + b 3 . ( a + b ) 3 = a 3 + 3 a 2 b + 3 a b 2 + b 3

1 3 + 2 3 + 3 3 + 4 3 + 5 3 + 6 3 = ( 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 ) 2 is the only one left, and by process of elimination it is true.

I know that this didn't really explain what the picture meant, but it sure is a way to get the solution!

I too did it in the same way but I think the picture has a lot to do with that formula.

The expression on the left corresponds to 1 + [2 * 2 + 2 * (2 * 1)] + 3 * (3 * 3) + [ 3 * (4 * 4) + 2 * (4 * 2) ] + 5 * (5 * 5) + [5 * (6 * 6) + 2 * (6 * 3)]

= 1^3 + 2^3 +.......6^3

Note : For every odd integer say m, there are m squares of m * m and for every even integer say n, there are (n-1) squares of n * n and 2 squares of (n*n/2)

It is evident from the above figure, that the top of the rectangle is made up of segments of increasing length from 1 to 6

The area of the square = (1+2+...6)^2 which is the expression on the RHS

But from the figure, it is clear that this is equal to the LHS

This corresponds to the following identity :

1^3 + 2^3 +........n^3 = (n * (n + 1/2))^2 where n * ( n + 1) / 2 = 1 + 2 +................n

Another way of simplifying the diagram would be to think of the nth square (n=2/4/6 ) as being divided into 2 parts with one part being positioned vertically and the other horizontally