Love thy neighbor

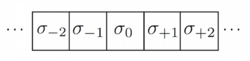

Consider a 1d array of

N

particles,

σ

i

, each in some state

∈

{

−

1

,

+

1

}

. The state can be thought of as the spin of the particle, and each particle can flip between the two states.

Consider a 1d array of

N

particles,

σ

i

, each in some state

∈

{

−

1

,

+

1

}

. The state can be thought of as the spin of the particle, and each particle can flip between the two states.

Each particle σ i interacts with each of its two next-door neighbors, σ i − 1 and σ i + 1 , and each interaction has an energy E ( σ a , σ b ) = − σ a ⋅ σ b Joules

This interaction encourages adjacent particles to have like state, and discourages adjacent particles from having unlike states.

Another energetic contribution comes from entropy. Energy states that have many possible arrangements are favored over those with few. A state with Ω arrangements has entropy S = k B lo g Ω , and has a free energy contribution − T S .

In general, at very high temperatures, entropy dominates energy and we expect each particle state to be − 1 or + 1 with probability 2 1 . At absolute zero, energy dominates entropy, and we expect the system to be in the lowest possible energy states, i.e. … , − 1 , − 1 , − 1 , … or … , + 1 , + 1 , + 1 , …

As we lower the system from high temperatures to absolute zero, we expect a transition from disorder to order at some critical temperature, T c : a battle between energy and entropy.

Suppose we have such a 1d lattice in the limit N → ∞ . As we lower T , at what temperature T c does the system first become ordered, i.e. trapped in one of the lowest energy states?

The answer is 0.0.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

2 solutions

That's exactly right. No matter how strong the interaction is between adjacent particles, the sheer number of available states for the single defect system will always win out against the energy. And obviously two defects, three defects, etc. have an increasing number of available states. By comparison, the energy of n defect systems only grows linearly in n .

What I understand is Tds is non zero finite while ds tends to infinity. So logically T has to tend to zero. Am I right?

We want to determine the temperature at which the system is first trapped into one of the ground states (shown below):

At any given temperature, we can look at the free energy, F ( T , σ ) = U ( σ ) − T S ( σ ) , as the equilibrium arrangement of the system will be the state of minimum F .

ground1

ground1

ground2

ground2

Because the energy of system goes like ∼ − i ∑ σ i ⋅ σ i + 1 it's clear that the interaction energy is minimized by the above shown states, because every σ i ⋅ σ i + 1 is 1.

On the other hand, because there are only two ground states, the entropy is minimized in the ground state. Staying in the ground states may therefore prevent the system from reaching its free energy minimum (since − T S is bounded at − k B T lo g 2 )

At the very least, we should expect the ground states to be favored at T = 0 since there will be no other way to lower the energy of the system.

Will the ground state be favored at any finite temperatures T > 0 ? Let's consider an excited state (not the first excited state), in which a single spin is flipped to point in the opposite direction.

excited

excited

The introduction of this defect raises the potential energy of the system by 2 ( − σ i − 1 ⋅ σ i and − σ i ⋅ σ i + 1 each change from -1 to ). How does it change the entropy? Let's estimate a lower bound on the entropy of this excited state.

If we only consider the number of system states in which a single spin is flipped away from the ground state, we get N since any of the N spins in the system can flip, leading to the same potential energy shift. This means that the entropy of the excited state is at least k B lo g N and the free energy is then Δ F ( N ) ≈ + 2 − k B T lo g N .

This is bad news for the ground state. While the flipped spin increases the potential energy by 2 (raising the free energy), it opens up a way to significantly increase the entropy (significantly lowering the free energy). No matter how low the temperature T is, we will always be able to find an N for which k B lo g N > 2 / T .

Because we're considering the limit of infinitely many particles in the lattice, this spells doom for the ground state. Any state is more stable than the ground state at non-zero temperature because of the dominance of entropy. That means that the first, and only, temperature at which the ground state will be stable is at T = 0 .

Consider the point when a system of N particles has only 1 particle that has not equilibrated with the rest of the system. The loss of usable energy , T Δ S , of the system when transitioning to zero particles should ideally equal the amount of potential energy gained. However, Δ S is proportional to the natural log of the number of particles in the system, while the increase in potential energy is a constant. Therefore, T c is inversely proportional to ln N , and as N tends to infinity T c tends to zero, resulting in an answer of 0 K .