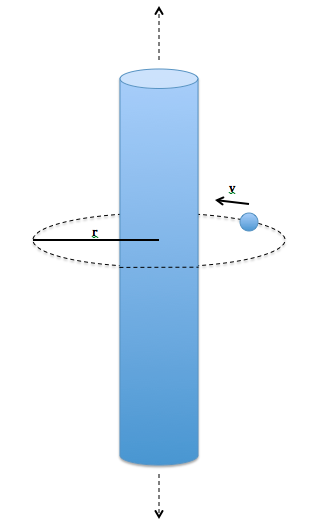

Orbiting cylinderworld

In your interstellar voyages, you have discovered a strange new planet! Instead of the traditional geoid shape, this planet is a nearly infinite cylinder!

In your interstellar voyages, you have discovered a strange new planet! Instead of the traditional geoid shape, this planet is a nearly infinite cylinder!

In order to safely enter orbit, you need to understand the nature of orbital mechanics near this strange planet. If you are in a circular orbit around this planet, and you wish to enter a larger circular orbit, will your speed in the larger circular orbit be higher, lower, or the same as your speed in the smaller circular orbit ?

Notes:

- The question asks about the speed in a larger orbit relative to the speed in a smaller orbit - not the speed needed to change orbits.

- You should treat this situation classically with Newtonian gravity; no special or general relativity.

- You may assume the planet's mass is distributed uniformly along the length of the cylinder

- You may assume that the length of the cylinder is effectively infinite (much larger than the radius of the orbits).

- You may assume other complicating factors like atmospheric drag or the dimensions of the spacecraft itself are negligibly small.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

The force of gravity near an infinite cylinder can be found using Gauss's law:

∬ S g ⋅ A = − 4 π G M

If the linear mass density is λ , then for a coaxial Gaussian cylinder of radius r and height h, Gauss's law becomes

2 π r h g = − 4 π G λ h r ^

(there is no contribution from the top or bottom of the Gaussian cylinder). Solving for g ,

g = − r 2 G λ r ^

In order for a mass m to move in a circular orbit, the gravitational force must provide the centripetal acceleration:

a c = g

r v 2 = r 2 G λ

Solving for v :

v ( r ) = 2 G λ .

From this last expression, we can see that the speed is dependent only on constants, not the radius of the orbit! Therefore the speed must be the same for any orbit, large or small.