Pierino and the Riddle of the Three Squares

Pierino is back!

Upon successfully solving the Riddle of the Papyrus , Pierino is adamant in impressing his math teacher again, with a new puzzle.

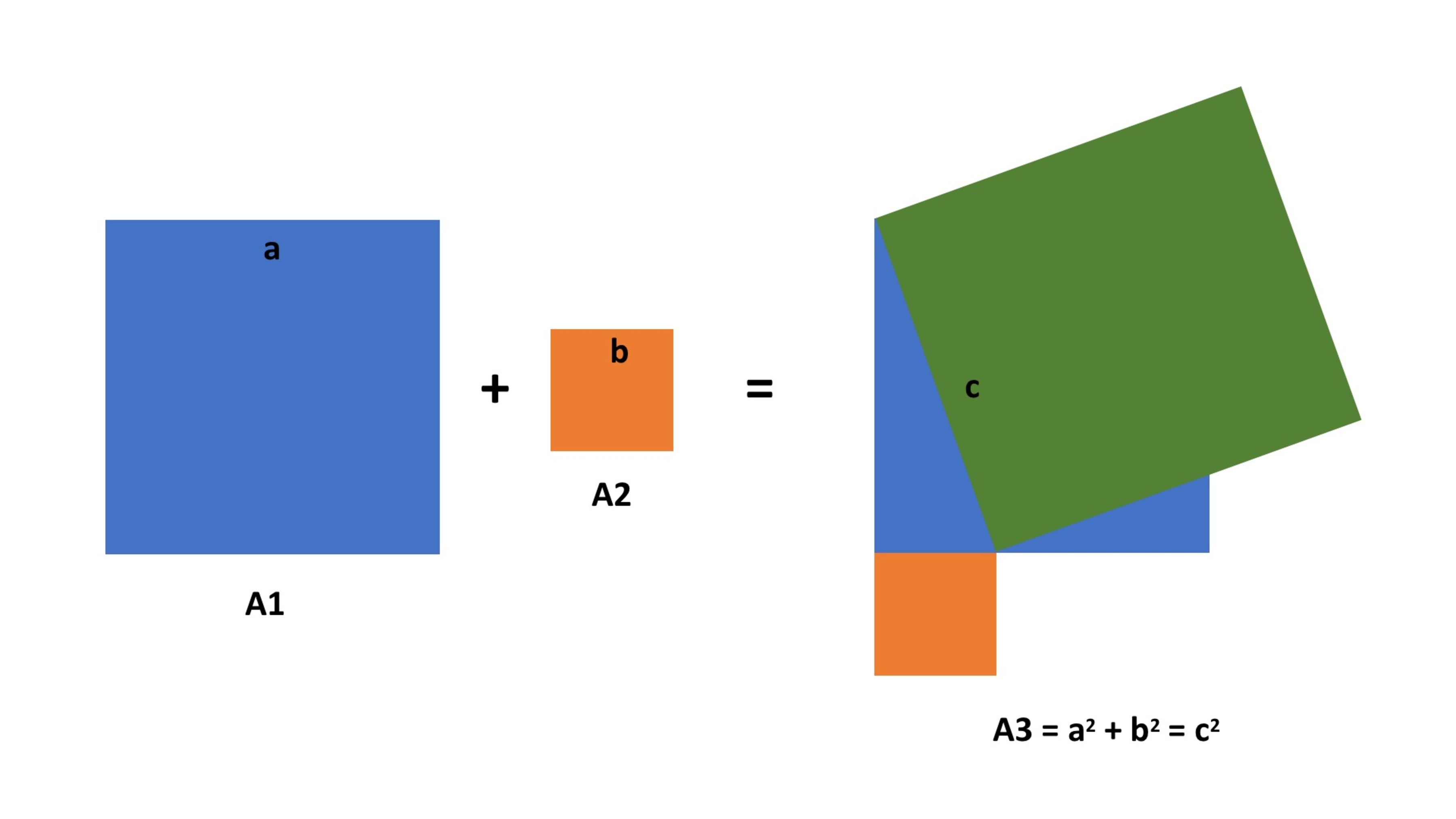

According to his book of History of Mathematics, Vedic people wrote appendices to the Vedas which give rules for constructing altars; such appendices are called

Sulbasutras

(800 BCE – 200 CE). One of the most famous among them describes how to find a square (A3) whose area is equal to the sum of two given squares (A1 and A2):

Upon reading about

Sulbasutras

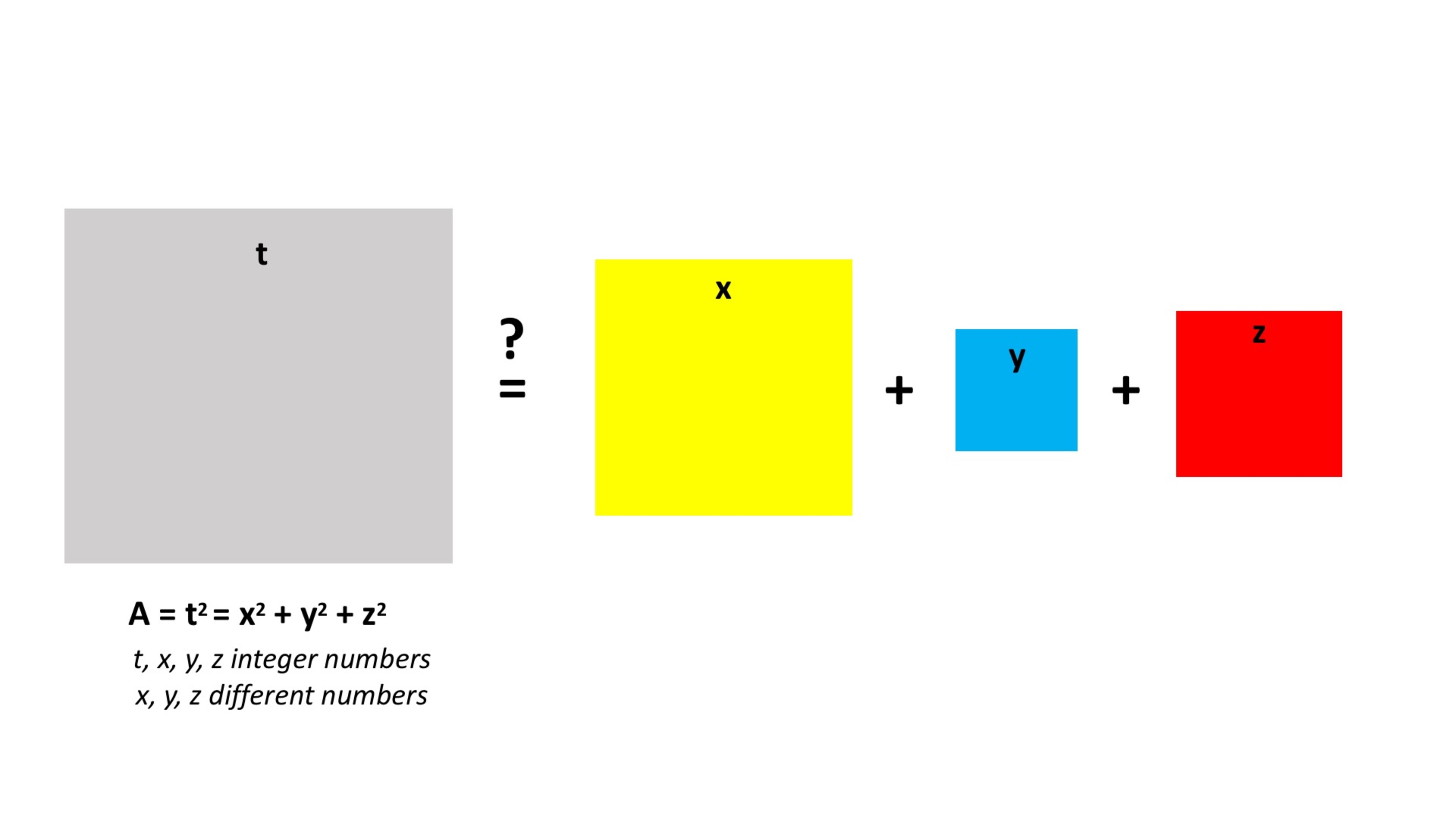

and the genius of the ancient Vedic mathematicians, Pierino got excited and decided to solve a riddle which is somehow related to the opposite situation: given a square with a certain area, find three

different

squares the sum of whose areas totals the initial square.

As Pierino does not feel comfortable with rational and irrational numbers, he is only considering

squares with integer sides

.

Upon reading about

Sulbasutras

and the genius of the ancient Vedic mathematicians, Pierino got excited and decided to solve a riddle which is somehow related to the opposite situation: given a square with a certain area, find three

different

squares the sum of whose areas totals the initial square.

As Pierino does not feel comfortable with rational and irrational numbers, he is only considering

squares with integer sides

.

In other words, is the following assertion true?

There exists a t -sided square (where t is an integer), whose area can be expressed as the sum of areas of 3 distinct squares.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

3 solutions

Let’s consider the equation

t 2 = x 2 + y 2 + z 2 with t , x , y , z ∈ N and x , y , z different.

We can consider

t = a + b

Then

( a + b ) 2 = x 2 + y 2 + z 2 = a 2 + b 2 + 2 a b

Therefore we can write that

x = a

y = b

z 2 = 2 a b

The three squares must have different sides, therefore

x 2 = z 2 ⇒ a 2 = 2 a b ⇒ a = 2 b

y 2 = z 2 ⇒ b 2 = 2 a b ⇒ b = 2 a

x = y ⇒ a = b

z 2 must be the perfect square of an integer number z , but it must also be the product of three factors ( 2ab ), therefore we can think of writing it as

z 2 = p 2 q 2

We can now arbitrarily assign factors a and b to p and q:

2 a = p 2 (1)

b = q 2 (1)

In this way, if a solution exists, it will have the shape that was imposed. If we do not find a solution, that will NOT be enough to say that no solution exists at all, but only that no solution exists of that shape. On the contrary, if we find a solution, that solution will have the shape given by the previous assumptions.

From (1) we can say that:

• a contains an odd number of factors “2”

• b is either an odd number or it contains an even number of factors “2”

Therefore, we can factorize a and b as:

a = 2 a 1 a 2 a 3 . . . a n 4 f

b = b 1 b 2 b 3 . . . b m 4 g

where f , g ∈ N

Thus:

2 a b = 2 ∏ i = 1 n 2 a i 4 f ∏ j = 1 m b j 4 g = z 2

2 a b = 4 f + g + 1 ∏ i = 1 n 1 a i 2 h i ∏ j = 1 n 2 b j 2 h j ∏ r 1 = 1 s 1 a r 1 2 h r 1 + 1 ∏ r 2 = 1 s 2 b r 2 2 h r 2 + 1 = z 2

with n 1 < n , n 2 < m .

The first two products correspond to the factors raised to an even power, while the latter two products correspond to the factors raised to an odd power.

If the expression

2 a b = 4 f + g + 1 ∏ i = 1 n 1 a i 2 h i ∏ j = 1 n 2 b j 2 h j ∏ r 1 = 1 s 1 a r 1 2 h r 1 + 1 ∏ r 2 = 1 s 2 b r 2 2 h r 2 + 1

has to be equal to a perfect square z 2 , then s 1 = s 2 = s , r 1 = r 2 = r , a r = b r ∀ r = 1 . . . s

We have obtained a description, in terms of factorization, of a and b :

• For both a AND b , odd factors should be raised to an even power;

• For both a AND b , if an odd factor is raised to an odd power, then the same factor must be present in the other number ( b or a ), raised to an odd power, so that the sum of the two powers is an even number;

• For a OR b , factor “2” must be raised to an odd power, and for the other number ( b or a ) factor “2” must be raised to an even power

Therefore, there are infinite sets of numbers t , x , y , z ∈ N and x , y , z different, that solve the equation

t 2 = x 2 + y 2 + z 2

where

t = a + b

x = a

y = b

z 2 = 2 a b

and where a and b can be represented as follows:

a = 2 ∗ 4 f ∏ i = 1 n 1 a i 2 h i ∏ r = 1 s a r 2 h r a + 1

b = 4 g ∏ j = 1 n 2 b j 2 h j ∏ r = 1 s b r 2 h r b + 1

where

a r = b r ∀ r = 1 . . . s

h r a , h r b ∈ N , ∀ r = 1 . . . s

Examples:

a = 2 , b = 9 ⇒ 2 2 + 9 2 + 2 ∗ 2 ∗ 9 = 4 + 8 1 + 3 6 = 1 2 1 = 1 1 2 = 2 2 + 9 2 + 6 2

a = 2 ∗ 3 2 = 1 8 , b = 5 2 = 2 5 ⇒ 1 8 2 + 2 5 2 + 2 ∗ 1 8 ∗ 2 5 = 3 2 4 + 6 2 5 + 9 0 0 = 1 8 4 9 = 4 3 2 = 1 8 2 + 2 5 2 + 3 0 2

One last note: a = 2 , b = 1 is not a solution because

a = 2 b

b = 2 a

a = b

Let ( a , b , c ) be a primitive Pythagorean triple (so a 2 + b 2 = c 2 ). Set x = a 2 , y = a b and z = b c . Then x 2 + y 2 + z 2 = ( a 2 ) 2 + ( a b ) 2 + ( b c ) 2 = a 2 ( a 2 + b 2 ) + b 2 c 2 = a 2 c 2 + b 2 c 2 = c 2 ( a 2 + b 2 ) = ( c 2 ) 2 Since ( a , b , c ) is primitive, a 2 , a b and b c are distinct. Thus, t = c 2 is a solution when c is the hypotenuse of any primitive Pythagorean triple.

As an example, taking the primitive Pythagorean triple 3 , 4 , 5 yields ( x , y , z , t ) = ( 9 , 1 2 , 2 0 , 2 5 ) . It is indeed true that 9 2 + 1 2 2 + 2 0 2 8 1 + 1 4 4 + 4 0 0 6 2 5 = 2 5 2 = 6 2 5 = 6 2 5

For other ways of generating ( x , y , z , t ) , read about Pythagorean quadruples .

One infinite set of solutions includes x = n , y = 4 n , z = 8 n , and t = 9 n for any positive integer n , since n 2 + ( 4 n ) 2 + ( 8 n ) 2 = ( 9 n ) 2 .