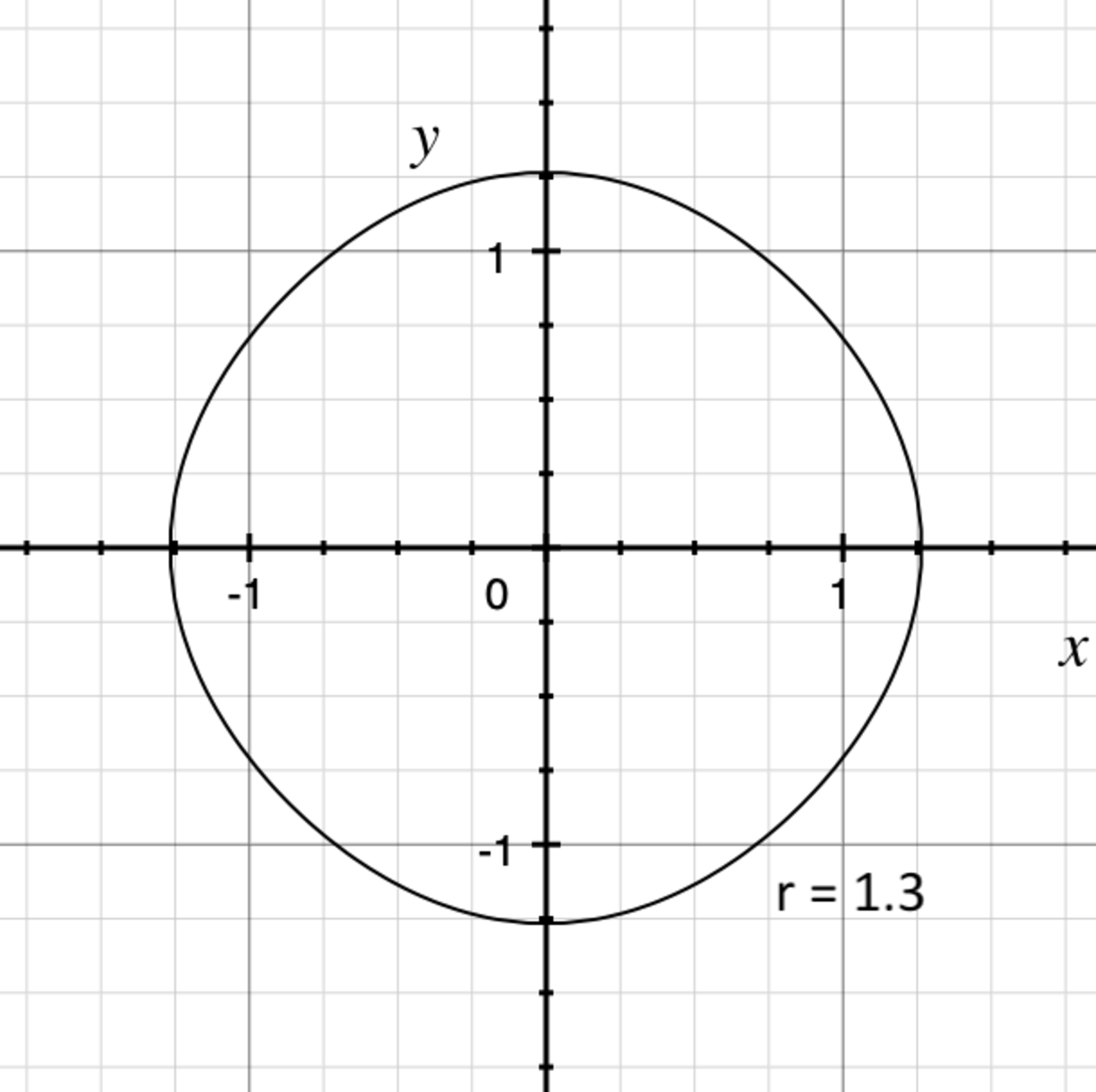

Pretty much a circle 1

Let be the area of the region in the xy-plane with and given by the equation Evaluate the following limit:

The answer is 6.2831853.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

For convenience, I'll refer to both the region and its area as A ( r ) . Let C ( r ) be the boundary of A ( r ) , ie the curve defined by cos x + cos y = r

We'll work out the limit by sandwiching A ( r ) between two circles.

Since for all θ , 1 − 2 1 θ 2 ≤ cos θ (with equality only at θ = 0 ), A ( r ) contains the region 1 − 2 1 x 2 + 1 − 2 1 y 2 ≥ r which is the interior of a circle centred at the origin with radius 4 − 2 r . Hence A ( r ) > π ( 4 − 2 r ) for all r .

Now, we'll find a region that contains A ( r ) .

Claim: the circle through the intersection points of C with the axes is always bigger than A ( r ) .

Another way to put this is that for a point P on C , the distance O P is maximised when x = 0 or y = 0 . (Slightly long-winded proof below.)

Now we have π ( 4 − 2 r ) < A ( r ) < π ( cos − 1 ( r − 1 ) ) 2

Dividing by 2 − r , this is

2 π < 2 − r A ( r ) < 2 − r π ( cos − 1 ( r − 1 ) ) 2

Two applications of L'Hôpital's rule show that as r → 2 , the expression on the right also tends to 2 π .

Hence by the squeeze theorem, in the limit, we have 2 − r A ( r ) → 2 π

I'm sure there must be a simpler proof using a clever inequality. Any ideas?

Proof of claim: we want to maximise x 2 + y 2 subject to cos x + cos y = r . We can do this with Lagrangian multipliers: define F ( x , y , L ) = x 2 + y 2 + L ( cos x + cos y − r )

The stationary points of F solve the optimisation problem. Taking partial derivatives, we need all three of the following to hold ∂ x ∂ F ∂ x ∂ F ∂ L ∂ F = 2 x − L sin x = 0 = 2 y − L sin y = 0 = cos x + cos y − r = 0

If neither x nor y is zero, we get the solutions x = ± y . In this case, x 2 + y 2 = ( cos − 1 2 r ) 2

But we can also make all three equations hold if (exactly) one of x or y is zero; we find x 2 + y 2 = ( cos − 1 ( r − 1 ) ) 2

It's (fairly) easy to show that cos − 1 2 r < cos − 1 ( r − 1 ) for 0 < r < 2 , so the first case corresponds to a minimum and the second to a maximum, and the claim is proved.