Real world Birthday Paradox

Birthday problem : What is the smallest value of such that out of randomly selected people, the probability that at least two of them share the same birthday exceeds 50%?

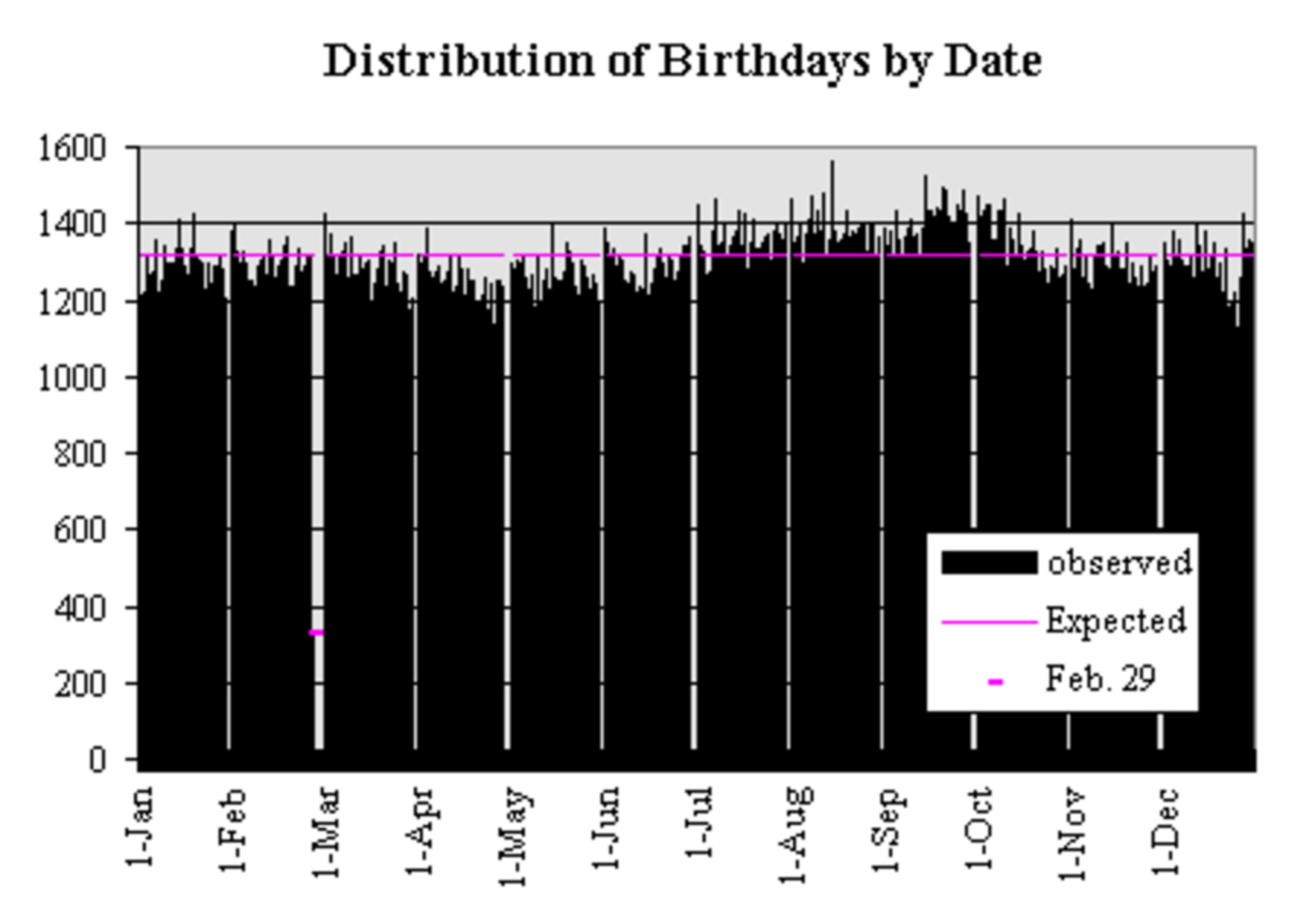

Making the assumption that birthdays are equally distributed, we conclude that the answer is 23. In reality, birthdays are unevenly distributed, and are more frequent in the summer months of July, August, September and October.

Distribution of birthday by date, sample population in United States

Distribution of birthday by date, sample population in United States

Given that the distribution isn't uniform, how would this impact the final analysis?

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

The more calender-concentrated the birthdays are, the more likely two of the randomly chosen people will have the same birthday. Taking a somewhat extreme case for purposes of demonstration, suppose a l l people in general are born in the four months listed. Assuming an even distribution within this 123-day time period, we would be looking for the minimum value of n such that

1 − 1 2 3 n 1 2 3 ∗ 1 2 2 ∗ 1 2 1 ∗ . . . . ∗ ( 1 2 3 − ( n − 1 ) ) ≥ 0 . 5 ,

which turns out to be n = 1 4 . Any peaks in the distribution, even if they aren't concentrated in one continuous period but occur in more than one peak, will have the same effect.