Rubber Physics (Part 1)

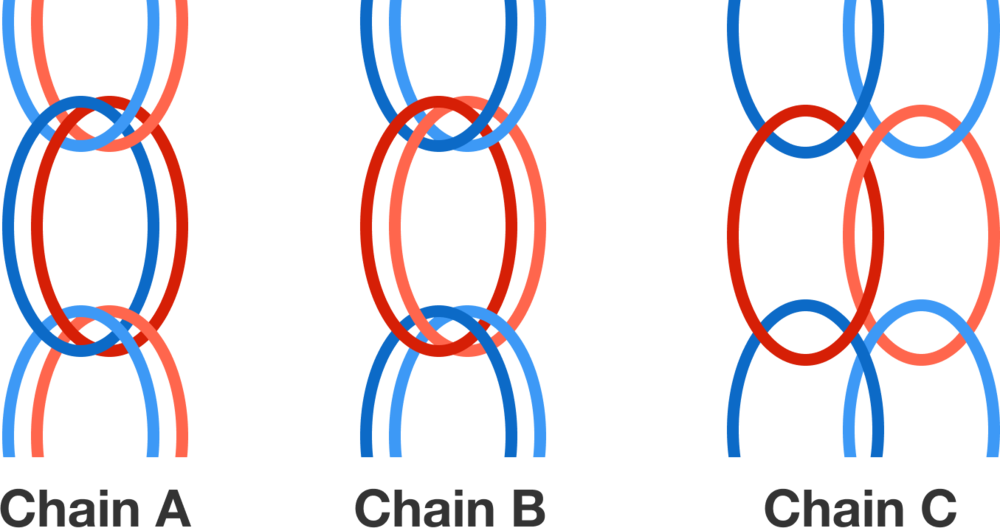

Amy makes bracelets out of colorful rubber bands. Playing around with the rubber, she notices that the red rubber bands are much stiffer than the blue ones. To get uniformly elastic bracelets, she tries to combine red and blue bands in equal parts. As a first step, she makes three different types of chains from the rubber bands outlined in the figure. However, while trying out the chains, Amy is surprised to find that one chain is much stiffer than the other two. Which rubber chain is it?

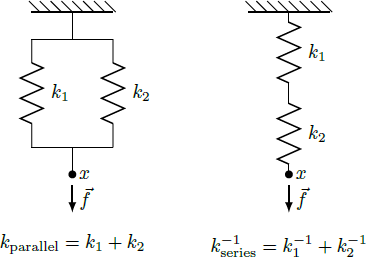

Hint: For small displacements x , a rubber band obeys Hook's law f = − k x with reversing force f and the force constant k . Figure out which force constant k results when two different rubber bands with force constants k 1 and k 2 are linked in parallel or in series. (The chaining of rubber bands resembles the parallel and series connection in an electrical circuit.)

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

7 solutions

I had this intuition and then I messed up the mathematical solution!

yeah, intuition rocks!

On my screen chain A only has one red band and two orange bands.

Log in to reply

Yes, same here! Colors should be chosen to avoid confusion.

The intuition really works on such examples. The only thing that got me really confused were the drawing errors on Chain C, as the lower blue rubbers aren't connected to any other.

I was stuck, i have no clue and sub to me on yt

I thought of it like this too. But the extra info confused me

An even simpler version: B & C are the same, and the answer is given that only one is stiffer...

If two rubber bands with force constants

k

1

and

k

2

are linked in parallel, the force

f

=

f

1

+

f

2

=

−

k

1

x

1

−

k

2

x

2

is divided between the two bands, while the displacement

x

=

x

1

=

x

2

is the same for both rubbers. Therefore, also the force constants add up:

k

parallel

=

−

x

f

=

k

1

+

k

2

However, if the two rubber bands are chained in series, on both act the same force

f

=

f

1

=

f

2

, but both bands have different displacements

x

1

and

x

2

, which add up to a net deflection

x

=

x

1

+

x

2

. The ratio of the displacements is equal the (inverse) ratio of the force constants:

⇒

⇒

⇒

⇒

f

=

−

k

1

x

1

x

1

x

2

x

f

k

series

=

−

k

2

x

2

=

k

2

k

1

=

x

1

+

x

2

=

(

1

+

k

2

k

1

)

x

1

=

−

k

1

x

1

=

−

1

+

k

2

k

1

k

1

x

=

−

k

1

+

k

2

k

1

k

2

x

=

k

1

+

k

2

k

1

k

2

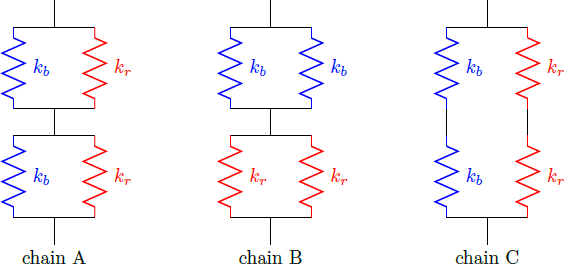

We can represent the different rubber chains A, B and C by combining parallel and series connection:

In applying the rules derived above, we get the following force constants for the sketched chain elements: ⇒ k A k B k C k B k A = k C k A = ( k 1 + k 2 ) + ( k 1 + k 2 ) ( k 1 + k 2 ) ( k 1 + k 2 ) = 2 k 1 + k 2 = ( k 1 + k 1 ) + ( k 2 + k 2 ) ( k 1 + k 1 ) ( k 2 + k 2 ) = 2 k 1 + k 2 k 1 k 2 = ( k 1 + k 2 k 1 k 2 ) + ( k 1 + k 2 k 1 k 2 ) = 2 k 1 + k 2 k 1 k 2 = 4 k 1 k 2 ( k 1 + k 2 ) 2 > 1 for k 1 = k 2 This inequality in the last calculation step follows from ⇒ ⇒ ( k 1 − k 2 ) 2 = k 1 2 + k 2 2 − 2 k 1 k 2 ( k 1 + k 2 ) 2 = k 1 2 + k 2 2 + 2 k 1 k 2 4 k 1 k 2 ( k 1 + k 2 ) 2 > 0 > 4 k 1 k 2 > 1

why is the squiggly model for c like that though it doesn't look like the reds and blues are in parallel construction with eachother in the prompt

Log in to reply

In the case c the rubber chain has cross connections between parallel elements, which are not taken into account in the equivalent circuit diagram. These cross connections do not change the result, since the parallel rubber bands each undergo the same displacement. (Transferring to an electrical circuit would mean that I have omitted a short between two points that have the same electrical potential anyway)

Maybe I should change the equivalent circuit anyway, so that it corresponds more to the drawing. However, that makes it a bit more complicated.

I think you have your Chain A and Chain B diagrams switched.

The solution presented by Markus Michelmann is excellent. However, the graphical representation of chain C is incorrect. The figure, Parallel[Series(Kb,Kb),Series(Kr,Kr)] should be replaced by Parallel[Series(Kb,Kr),Series(Kb,Kr)].

Chains B and C are not essentially different. This alone suggests that A is the answer.

In the limit where a red link is infinitely stiff, chain A cannot stretch at all, while in chain B and C the blue sections will stretch.

Either way, we see that the answer is A .

There is the distinct difference, that the blue bands on the bottom of C are not actually connected to the rest of the chain.

Look at the edge case of red not stretching at all and blue stretching with no effort. The blue links can essentially be removed. The only one that would still be held together is A, and it would be held together with no stretching at all.

Intuitively, a chain can only be as strong as its weakest link must extend to “a chain can only be a flexible as its most flexible link”. So chain A will be the least flexible.

Chain B and chain C are effectively identical: therefore chain A is the "odd one out".

Without all the numbers and math it appears that chain "A" is the only one that pairs the rubber bands such that each red band cancels out the flexibility of the blue ones. On a practical note how does Amy get the rubber bands linked? They're just regular circle type bands, right ?

There is a simple intuitive solution which is hinted at by the information that the red band are much stiffer than the blue ones.

Imagine that the links with only blue bands stretch really easily, and any link with a red band (even if it also has a blue band in parallel) is so stiff it hardly stretches at all.

Then it is easy to see that chains B and C will stretch a lot when a force is applied because they have weak blue links. Chain A, which has a red band in every link will hardly stretch at all.