Constant Integrand?

∫ − 1 3 ( arctan ( 1 + x 2 x ) + arctan ( x 1 + x 2 ) ) d x

If the above integral can be expressed as A π B , where A and B are natural numbers . Find A + B

The answer is 2.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

3 solutions

Moderator note:

Careful there, cot β = tan ( 2 π − β ) is indeed true, but so is cot β = tan ( 2 5 π − β ) . So, why can't we have α + β = 2 5 π ?

Bonus question : Can you find the fallacy in the working below?

Let y = arctan ( 1 + x 2 x ) + arctan ( x 1 + x 2 ) , then d x d y = 0 . So y is a constant. Substituting x = 1 tells us that y is a constant function and is equal to 2 π . Hence, our integral is equal to ∫ − 1 3 2 π d x = 2 π .

Response to the moderator's bonus question: arctan((1+x^2)/x) is undefined at x=0, and is therefore indifferentiable. Since it is not continuous on the interval {x|-1≤x≤3}, then sum of arctan(x/(1+x^2 )) and arctan((1+x^2)/x) is also discontinuous at x=0 (and thus in the range {x|-1≤x≤3}). The derivative of y does not give insight into the behavior of the function around x=0. Additionally, arctan(u)+arctan(1/u) = π/2 for positive u, and -π/2 for negative u.

Relevant wiki: Inverse Trigonometric Identities

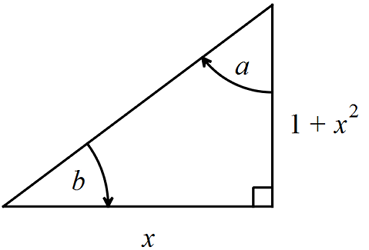

If x > 0 , then we can construct a right-angle triangle with base and height of x and 1 + x 2 .

Looking at the diagram, we have the triangles angle sum of a + b + 2 π = π , or equivalently, a + b = 2 π .

Because tan a = 1 + x 2 1 and tan b = x 1 + x 2 , then for x > 0 , ( arctan ( 1 + x 2 x ) + arctan ( x 1 + x 2 ) ) = a + b = 2 π .

Since the integrand (call it g ( x ) ) in question is an odd function , then the integral in question can be expressed as

∫ − 1 3 g ( x ) d x = = 0 ∫ − 1 1 g ( x ) d x + ∫ 1 3 g ( x ) d x = 0 + ∫ 1 3 2 π d x = ( 3 − 1 ) ( 2 π ) = π .

Hence, A = 1 , B = 1 ⇒ A + B = 2 .

Note : A common mistake for students to assume is that ( arctan ( 1 + x 2 x ) + arctan ( x 1 + x 2 ) ) is always equal to 2 π .

Moderator note:

Great setup in explaining why the integrand is, suprisingly, not always a constant!

Let's analyze the function, y = tan − 1 x 1

Substitute tan θ = x tan ( 2 π − θ ) = x 1 θ = tan − 1 x

So, y = tan − 1 [ tan ( 2 π − θ ) ]

Case 1 x ≥ 0

⇒ θ ∈ ( 0 , 2 π ) ⇒ ( 2 π − θ ) ∈ ( 0 , 2 π ) ⇒ tan − 1 [ tan ( 2 π − θ ) ] = ( 2 π − θ )

Case 2 x ≤ 0

⇒ θ ∈ ( − 2 π , 0 ) ⇒ ( 2 π − θ ) ∈ ( 2 π , π )

Remember that for ϕ ∈ ( 2 π , π ) , tan − 1 ( tan ϕ ) = ϕ − π

So, tan − 1 [ tan ( 2 π − θ ) ] = ( 2 π − θ ) − π = − 2 π − θ

∴ tan − 1 x 1 = ⎩ ⎪ ⎨ ⎪ ⎧ 2 π − tan − 1 x − 2 π − tan − 1 x for x > 0 for x < 0

So our integral, I = ∫ − 1 3 tan − 1 ( 1 + x 2 x ) + tan − 1 ( x 1 + x 2 ) d x = ∫ − 1 0 − 2 π d x + ∫ 0 3 2 π d x = π

Moderator note:

Yes. This essentially boils down to recognizing that the integrand is a piecewise function.

Let α = arctan ( 1 + x 2 x ) and β = arctan ( x 1 + x 2 ) ⟹ tan α = 1 + x 2 x and tan β = x 1 + x 2 . ⟹ tan α = tan β 1 = cot β = tan ( 2 π − β ) , ⟹ α = 2 π − β ⟹ α + β = 2 π for α > 0 and β > 0 . We note that when x < 0 , α , β < 0 , and α + β = − 2 π . Therefore, we have:

I = ∫ − 1 3 ( arctan ( 1 + x 2 x ) + arctan ( x 1 + x 2 ) ) d x = ∫ − 1 3 ( α + β ) d x = ∫ − 1 0 ( α + β ) d x + ∫ 0 3 ( α + β ) d x = ∫ − 1 0 − 2 π d x + ∫ 0 3 2 π d x = − 2 π + 2 3 π = π

⟹ A + B = 1 + 1 = 2