Square vs Rhombus

A rhombus and a square have the same side length, but are not congruent. Which has the smaller area?

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

18 solutions

Moderator note:

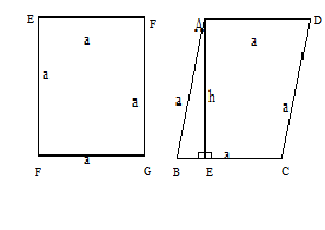

The parallelogram area formula is the height multiplied by the base length. It can be justified via a dissection as shown here.

The square area formula is also the height multipied by the base length.

So in words, the proof is essentially that if the square is tilted to become a rhombus, the height must necessarily be smaller; therefore the area of the parallelogram must also be smaller.

Very nice solution!

Very clever

Isn't a square a form of a rhombus? So the answer should be rhombus <= square... which wasn't offered, so indeterminate.

Log in to reply

The problem stated that the rhombus and the square were not congruent.

Consider a square of side length = a . If we pick opposite corners and stretch them. The resulting figure will be a rhombus with side length = a . Then shouldn't they have equal area and equal perimeter.

Log in to reply

If you "stretch" the square from opposite corners, the resulting rhombus will have longer side length than the square. This is more like holding one side and pushing the square over from one of the adjacent sides.

Screw geometry solution See inequality solution Let S be the common side length Let the two diagonals be D1 and D2 Then as the diagonals bisect at 90° ({D1}²/4)+({D2}²/4) = s^2 Apply am-gm 2{d1}×{d2} < 4s² ½{D1}×{D2} < s²........(1) But ½{D1}×{D2} = area of rhombus S² = area of square From (1) we get that Area of rhombus < Area of square

Log in to reply

I am going to be a grunt worker forever...because that seems to be the only good thing I can be successful at.

oh wow nice

I guess you need to know what congruent means...

Log in to reply

A valid point. This is mathematics, not damn literary english! ... haha.gif

Also, if you can’t work it out, you’re therefore unable to determine the right answer, so picking the last answer should be correct;-)

Log in to reply

Technically correct is always correct. Right?

Log in to reply

according to Futurama (Hermes' boss) that's the best kind

I didn't read the question and worked out the biggest area.

What convinced me of the fact that the Rhombus has smaller area is that you can draw a sequence of Rhombuses of ever smaller area, having the same length sides, until you get a Rhombus that has nearly zero area.

Let the side length for both the figures be a units.

Area of rhombus = a 2 sin θ

Area of square = a 2

One can clearly see that in case of the square, θ = 9 0 o , so rhombus has to have the smaller area.

My solution exactly.

i think it is rombus but 2 seconds later i think it is square

Ashfaq, can u elaborate on your solution please? That would be helpful

Log in to reply

sin 9 0 o = 1 , so the square will have the largest area. This formula comes from the triangle area formula using sine. Giving 2 the length of two sides of a triangle ( a and b ) and the angles formed between they ( t h e t a , the area of this triangle will be sin θ ⋅ 2 a b .

If we cut the rhombus among its diagonal, we will have two congruent triangles. Two of the sides of this triangles will be a (side of the rhombus) and the angle between they will be θ . Then the area of the rhombus can be written as \(a^2 \sin \theta).

Note that two adjacent angles in a rhombus are supplementary angles so the have the same sine. Also, the angle can only in the range \(0 < \theta < 2\pi\), and in this range the largest value for sin θ is 1, when θ is a right angle.

Exactly, but in case of θ = 9 0 o they are the same. Because there is no restriction to the angle we have a possible solution for equal area and thus it cannot be determined which is smaller.

The area of a square is ( S i d e ) 2 and the area of rhombus is B a s e × H e i g h t .

Consider the set-ups below:

Notice that A E is perpendicular to B C so, A E 2 = A B 2 − B E 2 = a 2 − B E 2 . So, definitely, E F > A E .

The rest is left to the reader.

wouldn't you have equal areas by this picture? the height in the rhombus is the same as the height of the sides in the rectangle. multiplying equal base by height or rhombus or height of rectangle is the same area. I understand the math proof with Pythagorean theorem but I am visually / geometrically confused.

Log in to reply

This is only a 2D representation of a 3D Reflection. For a square solid piece with equal sides to become a rombus with thoes same dimensions. The only solution in the 3D dimension, to set any one side of the square parallel to an axis(eg, x-axis), and rotate across the line of axi's ~ Axis... Now for the object to become a rombus the viewing point of image matter. For Different viewing points you get a unique representation of the object. The viewing point/plane for this problem would ideally be initially parallel to the face of the square...some y-distancd away.., then rotate that plane aproximately 33° or 45°(Aproximate Haven't actually calculated these..) on the xy plane. And then from that viewing plane when looking at the Square object; with one of its side having a Vector of (1,0,0) If (x,y,z); start rotating on the zy Plane in the positive y direction. From the viewing point the image of the Solid Square rotating to about 45° in the positive y-direction would form into and image(2d representation) of a rhombus. And the math proves this problem has a 3D solution by having mathematical proof that the height is different. This is true because the angle of the rotating Square is crearting a circle on the ZY ( A plane perpendicular to the ZY plane ). And the square was at PI/2 radians but at radians between (0,pi/2) the y-component is smaller. Therefore the height of the rhombhs is equivalent to the y-component when on the Image. This proves that a rombus is just a 2D representstion of a flat Square viewed from its front and angled down towards the ground. And math is the way humans understand the fabric of the symmetric vast yet beautiful universes.

The square has greater area the given answer is sure wrong.

A very neat solution, well done :)

Yes. This makes sense now.

I drew both the rhombus and the square on a piece of blank paper then measured them, it seemed like they had an equal area. I think I should have just figured it out because the rhombus DID look a lot smaller than the square. I would rate this problem a 1 because now that I understand it, it seems fairly easy.

Formulas explain this much better... even more so when simply stated as in your first sentence. Thanks for this (whole) explanation!

if the formula for square and rhombus both could be shown as 1/2 d1 d2 (similar to 1/2*d^2 for square) and they have similar side length... ugh, quite complicated for me =)

Great use of applying Pythagorean theorem in the last step! +1

Best explanation

Nailed it.

Your square is rectangle?

Consider an extreme case - a rhombus that is incredibly skinny yet still has the same side length as a square. In other words, the acute angle between two adjacent sides of the rhombus is very small. Clearly, the area of the rhombus is much smaller than the area of the square, so that is our answer.

Split the Rhombus into two triangles. The area is base * height. The new base is the length of the dividing line and is always less than the length of any side. and the new height is always always less than the length of any side therefore the product of two reduced numbers cannot sum up to side*side

-

Let's recall that─ a square is an special case of rhombus. A rhombus whose one angle (consequently, each angle) is a right angle is a square.

-

The area of a rhombus with side length s and one angle θ is s 2 sin θ . How? Let me provide a hint: the area of a triangle, whose one angle is θ , and a and b are the two adjacent sides of the angle, is 2 1 a b sin θ .

-

Now, as 0 ∘ < θ < 1 8 0 ∘ , the maximum area of a rhombus with side length s occurs at θ = 9 0 ∘ , that is when the rhombus is also a s q u a r e .

-

So, if the square and the rhombus are not congruent, but have equal side length, then the rhombus has smaller area .

Solve this by looking at an extreme case. If the rhombus is completely flattened it will have zero volume. So the rhombus has less area than the square.

consider a square made of frames put that frame on ground

now give some bearings to lower two vertices and give it a push

after some time the whole frame collapses and has zero area

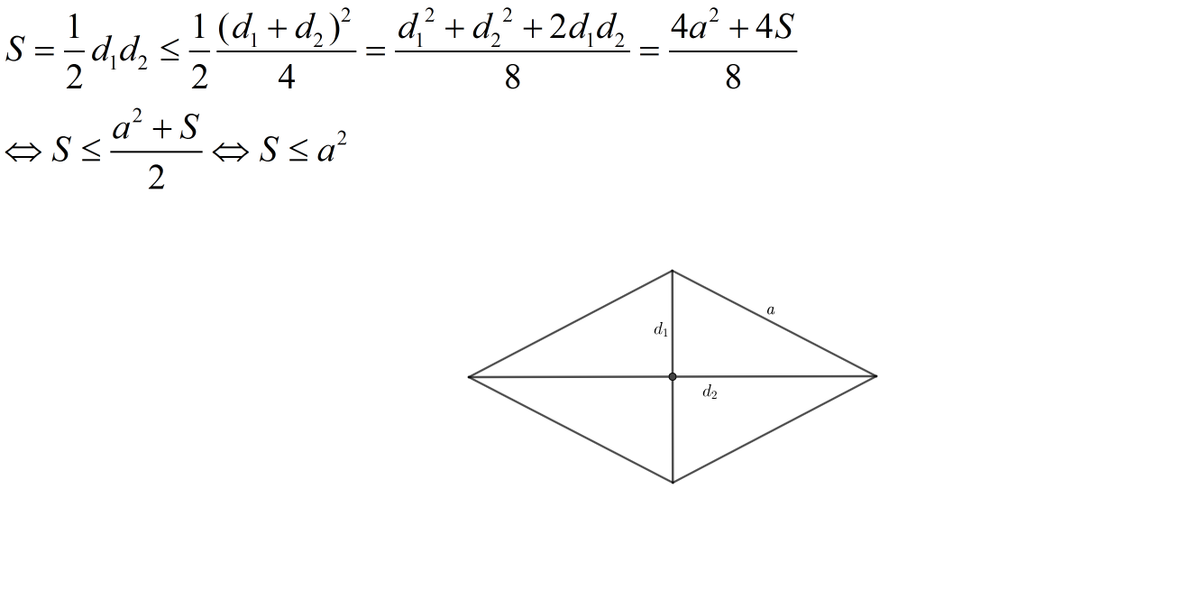

Let the rhombus area is S and d1, d2 are its diagonal.

We have:

And: a^2 is the quare area.

So the rhombus has to have the smaller area.

And: a^2 is the quare area.

So the rhombus has to have the smaller area.

The area of a square or rhimbus is given by a² sinA. Where a is it's an arm and A is angle between two adjacent arms. For square A=90° and for rhombus A= lesser or greater than 90°. Since sin90°=1 and for other angles between 0° to 180° it is less than 1. That's why rhombus has smaller area.

Extend the folding of the square to the limit and it reaches zero area. So the area diminishes the moment the square starts to fold!

Intuitively, if you allow the rhombus to deform further it becomes flatter until the area must become zero. Therefore, the area of any rhombus that is not a square must be less than that of the square.

The rhombus can be made be squeezing opposite corners of the square. As it is squeezed its area decreases to zero - it never increases.

Let the length be 2 cm:

Then the area of the square is 4 c m 2

The area of rhombus is 2 4 3 .

∴ The area of rhombus is less than the area of the square

I found the area of the rhombus by dividing it into 4 right-angled triangles as we know that a rhombus is made of 2 equilateral triangles

Those are isosceles triangles... We get two equilateral ∆s only when one of the angles of rhombus is 60°

Imagine "pulling" from two corners of the square in order to get a rhombus, and you continued until it folds into a straight line which has zero area. So the area has to go from l^2 to 0 and the area of the rhombus is in between

A Rhombus always has four equal sides; a square always has four equal sides. A square always has four 90 degree angles. The angles of a rhombus can be any measure (each pair of opposite angles will be equal, and all four will always add up to 360). A square can also be defined as a parallelogram with equal diagonals that bisect the angles. If a figure is both a rectangle (right angles) and a rhombus (equal edge lengths), then it is a square. ... A square has a larger area than any other quadrilateral with the same perimeter.

The area of a square is (side)^2 or a^2 (Considering side length = a) and the area of rhombus is Base*Height or a^2 sinϴ. the acute angle between two adjacent sides of the rhombus is very small. Clearly, the area of the rhombus is much smaller than the area of the square, so that is our answer.

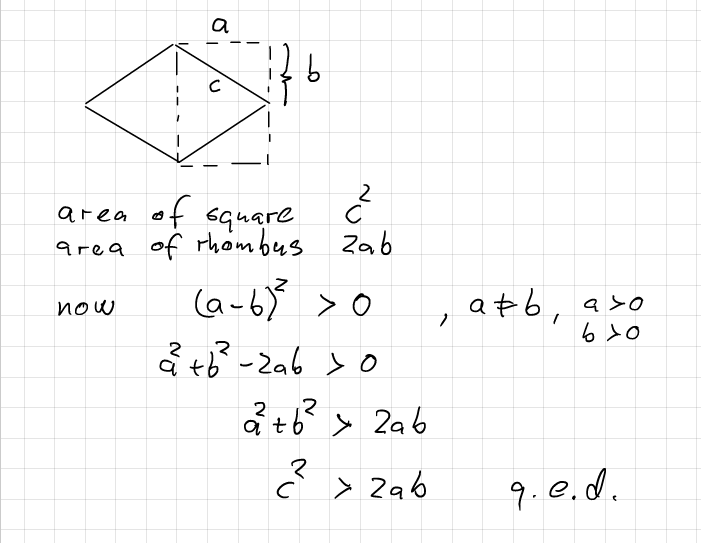

There is a nice, geometrical solution to the question.