Three's a crowd

How many ways can we arrange 10 identical black balls and 10 identical red balls in a line, such that no more than 2 balls of the same color ever appear in a row?

The answer is 8196.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

4 solutions

Moderator note:

Generalizing the problem to m black balls and n red balls allowed us to easily set up the recurrence relation, compared to considering just m = n black/red balls. This trick of relaxing a constraint is useful when we feel that it is overly / unnecessarily restrictive, and relaxing it could lead to more flexibility.

Once we have a workable recurrence relation, we can they try and for the closed form (Mark), or evaluate sufficient terms to get the numerical answer (Laurent).

Terrific solutions! Thank you for posting them. The second "blocking" solution was how I was proceeding, and you've formalized it in a much cleaner way than I could have. (Having seen your solutions in the past I was actually hoping you were going to post one for this problem. :) )

Log in to reply

If you want a concrete formula for the number of ways of putting 2 n balls in a line, n of each, try 2 k = 0 ∑ 2 u = 0 ∑ ⌊ 2 1 n ⌋ − k b = 0 ∑ m i n ( u , n − 2 k − 2 u ) b ! ( b + k ) ! ( u − b ) ! ( n − b − 2 u − 2 k ) ! ( n − u − k ) ! Try putting together a number of dominoes of different shapes: B R B B R B R R B B R R possibly followed by up to 2 dominoes of the shape B Count how many of each type you need to get the right total length 2 n and equal numbers of R and B, and add up the associated multinomials. Then times by 2 , since you could have started with R instead of B. In the above sum, k is the number of B dominoes, b is the number of BBR dominoes, and u is the number of BBR and BBRR dominoes together.

On the other hand, simply generalising the blocking argument gives the simpler formula: C n = 2 m = ⌈ 2 1 n ⌉ ∑ n ( n − m m ) 2 + 2 m = ⌈ 2 1 n ⌉ ∑ n − 1 ( n − m m ) ( n − m − 1 m + 1 )

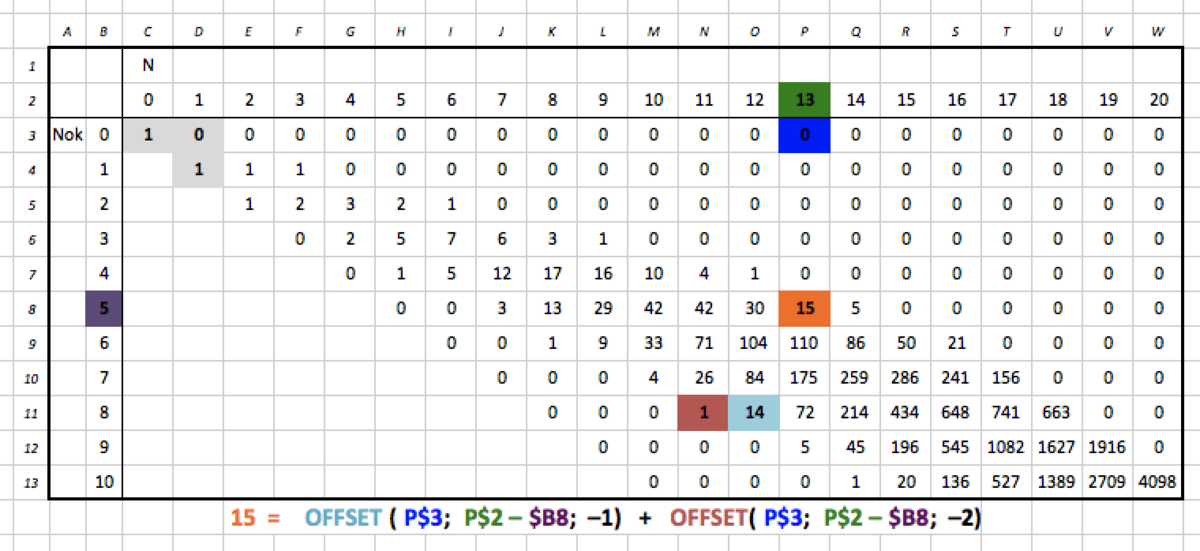

Using same notation as Mark Hennings, and as we have R m , n = B n , m by symmetry, we can make a unique function S t ( x ) = B x , t − x = R t − x , x that gives the number of sequences of t balls that begins with a color present x times. And thus we have the relation: S t ( x ) = S t − 1 ( t − x ) + S t − 2 ( t − x ) .

Starting point is S t ( x ) = 0 if x < 0 or x > t , S 0 ( 0 ) = 1 , S 1 ( 0 ) = 0 , S 1 ( 1 ) = 1 .

We're looking for S 2 0 ( 1 0 ) = 4 , 0 9 8 . As the sequences can begin with a red or a black ball, we multiply by 2: 2 ⋅ 4 0 9 8 = 8 1 9 6 .

A python program:

def S(t,x):

if x < 0 or x > t:

return 0

if t == 0:

return 1

if t == 1:

return x

return S(t-1,t-x) + S(t-2,t-x)

print 2*S(20,10)

An Excel formula:

* Not a solution, just an entry so that others can comment on the problem *

This scenario is analogous to a grid path from ( 0 , 0 ) to ( 1 0 , 1 0 ) avoiding any 3 or more consecutive steps either to the right or up. The OEIS entry is here . I used the grid path approach up to n = 5 and then accessed OEIS to find the rest of the pattern, but more formally we can use the method outlined here . Any more elegant solutions are welcome.

[Edit: As pointed out by Mark, this comment is not valid because I didn't add the condition of equal balls.]

The approach that I would consider is to set up a recurrence relation for the number of suitable arrangements conditional on the color of the last 2 balls. IE Let A n be the number of arrangments of n balls that end with B B , and B n , C n D n defined for B R , R B , R R respectively. Then we have A n + 1 = C n and similar equations, while we want to find ∑ A n .

We have a one-step linear recurrence, and can verify that the matrix is diagonalizable with eigenvalues 2 1 ( 1 ± 5 ) , 2 1 ( − 1 ± 3 i ) .

Log in to reply

But how does this take account of the need for an equal number of red and black balls? The expression A n + B n + C n + D n is the number of sequences of length n that contain no more than two red or black balls in a row, but such a sequence of length 2 0 does not necessarily have 1 0 red and 1 0 black balls.

Log in to reply

Ah true. I didn't account for that condition.

The answer is the coefficient of b 1 0 r 1 0 in 2 ( ∑ i = 5 1 0 ( b + b 2 ) i ( r + r 2 ) i + ∑ i = 6 1 0 ( b + b 2 ) i ( r + r 2 ) ( i − 1 ) ) .

Once this is granted a computer algebra package can do the work to find the answer 8 1 9 6 .

Explanation.

My idea was to extend the formula for restricted compositions in what I hope is an obvious way (at least for those who understand why the restricted partition formula works!). For the restricted compositions formula see the end of this article

Here are some pointers to help explain the connection.

An acceptable line consists of sections of alternating colour, with one or two balls in each section. There must be no fewer than ten sections (with two balls in each section) and no more than twenty sections (with one ball in each section). This explains the limits in the sums.

The sums inside the large parenthesis refer to lines starting with a black ball, which is why the initial factor of two is needed to find the answer for lines staring with either colour.

The first sum refers to lines with an even number of sections, the second sum to lines with an odd number of sections.

Wow, great approach! I liked how you translated all the conditions in the problem into a polynomial. If we changed the limits of the sums to ∑ i = 1 ∞ , then the coefficient of b m w n would give us the number of arrangements with m black balls and n red balls for any m , n .

Thanks for your comments Pranshu.

I particularly liked your observation that my solution is easily generalised by pushing the limits down to 1 and up to ∞ . The answer can be generalised in another direction as well. If, for instance, each black section can contain two or three balls, and each red section can contain one or four balls, then the brackets in the sums become ( b 2 + b 3 ) and ( r + r 4 ) .

Let B m , n be the number of acceptable sequences containing m black balls and n red balls, where the first ball is black, and let R m , n be the number of acceptable sequences containing m black balls and n red balls, where the first ball is red. Then we have B m , 0 B 0 , n B 1 , n = = = { 1 0 0 ≤ m ≤ 2 m ≥ 3 δ n , 0 R 0 , n R 0 , n R m , 0 R m , 1 = = = { 1 0 0 ≤ n ≤ 2 n ≥ 3 δ m , 0 B m , 0 Moreover we have B m , n R m , n = = R m − 1 , n + R m − 2 , n B m , n − 1 + B m , n − 2 m ≥ 2 , n ≥ 0 m ≥ 0 , n ≥ 2 Consider the generating functions B ( x , y ) = m , n ≥ 0 ∑ B m , n x m y n R ( x , y ) = m , n ≥ 0 ∑ R m , n x m y n Then ( y + y 2 ) B ( x , y ) = m , n ≥ 0 ∑ B m , n ( x m y n + 1 + x m y n + 2 ) = m ≥ 0 , n ≥ 1 ∑ B m , n − 1 x m y n + m ≥ 0 , n ≥ 2 ∑ B m , n − 2 x m y n = m ≥ 0 , n ≥ 2 ∑ R m , n x m y n + m ≥ 0 ∑ B m , 0 x m y = R ( x , y ) − m ≥ 0 , 0 ≤ n ≤ 1 ∑ R m , n x m y n + ( 1 + x + x 2 ) y = R ( x , y ) − 1 − ( 1 + x + x 2 ) y + ( 1 + x + x 2 ) y = R ( x , y ) − 1 and, similarly, ( x + x 2 ) R ( x , y ) = B ( x , y ) − 1 Thus we obtain B ( x , y ) = 1 − ( x + x 2 ) ( y + y 2 ) 1 + x + x 2 R ( x , y ) = 1 − ( x + x 2 ) ( y + y 2 ) 1 + y + y 2 If Z m , n = B m , n + R m , n is the number of acceptable sequences containing m black balls and n red balls (starting with either colour), then Z m , n is the coefficient of x m y n in the series B ( x , y ) + R ( x , y ) = 1 − ( x + x 2 ) ( y + y 2 ) 2 + x + x 2 + y + y 2 Expanding this series (initially as a double series in x + x 2 and y + y 2 , and then getting our hands dirty), we can evaluate the coefficient of x 1 0 y 1 0 as 8 1 9 6 .

An alternative approach is to note that the black balls must occur in N blocks, where 5 ≤ N ≤ 1 0 , and that the red balls must occur in M blocks, where 5 ≤ M ≤ 1 0 . The numbers N , M of blocks of black and red balls must be compatible with each other, in that ∣ M − N ∣ ≤ 1 . Thus the set of possible pairs ( M , N ) of block counts is S = { ( 5 , 5 ) , ( 5 , 6 ) , ( 6 , 5 ) , ( 6 , 6 ) , ( 6 , 7 ) , ( 7 , 6 ) , ( 7 , 7 ) , ( 7 , 8 ) , ( 8 , 7 ) , ( 8 , 8 ) , ( 8 , 9 ) , ( 9 , 8 ) , ( 9 , 9 ) , ( 9 , 1 0 ) , ( 1 0 , 9 ) , ( 1 0 , 1 0 ) } The number of acceptable sequences containing N black blocks and M red blocks is X N , M = ⎩ ⎨ ⎧ ( 1 0 − N N ) ( 1 0 − M M ) 2 ( 1 0 − N N ) ( 1 0 − M M ) N = M N = M To see this, put 1 black ball in each of the N blocks, and then choose which 1 0 − N of these N blocks will contain a second black ball. A similar argument applies to the red blocks. When N = M , the colour with the larger number of blocks must come first, and it is clear that the number of acceptable sequences is X N , M = ( 1 0 − N N ) ( 1 0 − M M ) . If N = M then either colour could occur first, and so we need to double this expression to determine X N , M .

Elementary computation now tells us that ( N , M ) ∈ S ∑ X N , M = 8 1 9 6