Tiling

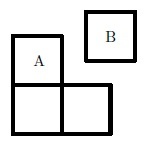

A 2 × 2 square is cut into two pieces, A , which has area 3, and B , which is a square of area 1 , as shown in the figure below.

A 2 × 8 grid is to be tiled with various pieces having shape A or B . Pieces of shape A can be rotated by 0 , 2 π , π , or 2 3 π before being placed. Subject to the condition that three pieces of shape B cannot occur on the grid in such a way that they could be replaced by a piece of shape A , how many different tilings are there of the grid?

The answer is 556.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

6 solutions

This makes it look so easy. Well done!

I normally don't comment on this, but that really is a very keen solution. You got my vote up ;-)

This was my exact solution but I accidentally pressed the back-page button whilst typing it :P well done James!

We can solve this problem using recursion. Let a n be the number of tilings of a 2 × n grid such that neither of the rightmost two squares is occupied by a piece of shape B. Let b n be the number of tilings of a 2 × n grid such that one of the rightmost two squares is occupied by a piece of shape B. Let c n be the number of tilings of a 2 × n grid such that both of the rightmost two squares are occupied by a piece of shape B.

There are 7 ways to add at least one column to a 2 × n grid. First of all, we can add a 2 × 1 rectangle made of two pieces of shape B. This rectangle can only be added to a configuration if neither of the rightmost two squares is occupied by a piece of shape B.

Secondly, we can add a 2 × 2 square made of one piece of shape A and one piece of shape B. There are four ways to orient this square. If the piece of shape B is on the left, the square can only be added if a configuration does not have both rightmost two squares pieces of shape B. If the piece of shape B is on the right, the square can always be added.

Thirdly, we can add a 2 × 3 rectangle made of two pieces of shape A. There are two ways to orient this rectangle, and it can be added to any configuration.

From this, we determine a recurrence: a n b n c n = 2 ( a n − 3 + b n − 3 + c n − 3 + a n − 2 + b n − 2 ) = 2 ( a n − 2 + b n − 2 + c n − 2 ) = a n − 1

Finally, we can form a table, where s n = a n + b n + c n : a n b n c n s n 1 0 0 1 1 2 2 2 0 4 3 2 2 2 6 4 1 0 8 2 2 0 5 1 6 1 2 1 0 3 8 6 4 8 4 0 1 6 1 0 4 7 9 6 7 6 4 8 2 2 0 8 2 5 2 2 0 8 9 6 5 5 6

The answer is s 8 = 5 5 6 .

Nice solution!

As always, I got the correct recursion but messed up in the arithmetic. -.-

Log in to reply

Yes, I always mess up on the arithmetic at least once. I triple-check before the second submission...

Consider three different forms of tiling -

One, P , in which the leftmost edge of the grid is made up of two B pieces next to each other.

Another, Q , where the leftmost edge is made up of an A and a B piece (either way round).

A final, R , with the leftmost edge made up of a single A piece (in either possible orientation).

Any tiling of the 2 × 8 grid must be exactly one of these forms, so the total number of tilings is equal to the sum of these three types.

P − B ⋯ B ⋯ Q − A B A ⋯ A ⋯ R − A A A ⋯ . ⋯

Now we set up recurrences for each of these three tilings.

For P , it is relatively simple. Starting from the left, we have two B pieces, but the restriction in the question prevents us from putting any P or Q tilings on the right of them; otherwise, there would be an A -shaped block of B s. Any R tiling is possible though, because the A and 2 B pieces can coexist happily. Therefore, P n = R n − 1 .

For Q , there are two possible starting positions, in which the A and B pieces make a square and the B piece is against the left side. To then extend either of these two positions, any of the other sorts of tilings could be appended to the right, because a flat end of an A piece is the connection. Therefore, noting that the starting position consumes two units of length, Q n = 2 ( P n − 2 + Q n − 2 + R n − 2 ) .

For R , there are now 4 possible starting positions. In two of them, the A and B pieces again make a square though with the B piece on the right, and in the others there are two A pieces making a 2 × 3 rectangle. In the former case, any adjacent tiling except a P one is acceptable, and in the latter any tiling at all is allowed. This means that R n = 2 ( Q n − 2 + R n − 2 ) + 2 ( P n − 3 + Q n − 3 + R n − 3 ) .

Starting from n = 1 (we cannot start from n = 0 because P 0 , Q 0 , R 0 refer to the same empty arrangement and are no longer unique), we see by inspection that

P 1 = 1 , Q 1 = 0 , R 1 = 0 P 2 = 0 , Q 2 = 2 , R 2 = 2 P 3 = 2 , Q 3 = 2 , R 3 = 2

Then we apply the recurrence, obtaining

P 4 = 2 , Q 4 = 8 , R 4 = 1 0 P 5 = 1 0 , Q 5 = 1 2 , R 5 = 1 6 P 6 = 1 6 , Q 6 = 4 0 , R 6 = 4 8 P 7 = 4 8 , Q 7 = 7 6 , R 7 = 9 6 P 8 = 9 6 , Q 8 = 2 0 8 , R 8 = 2 5 2

Finally, the total number of ways to tile a 2 × 8 grid is equal to P 8 + Q 8 + R 8 = 5 5 6 .

your solution is extremely clear and easy to understand, thank you (:

We can solve it by obtaining a set of recurrence equations:

Let a n denote the number of ways of tiling for 2 × n grid.

Let b n indicate the number of sets ending with B on top and bottom squares (takes 2x1 space)

Let c n indicate the number of sets ending with A B and A B (takes 2x2 space)

Let d n indicate the number of sets ending with B A and B A (takes 2x2 space)

And let e n indicate the number of sets ending with A A (takes 2x3 space)

The required answer the sum: a n = b n + c n + d n + e n

The recurrences are:

b n = d n − 1 + e n − 1 ,

since ending with BB requires that previous tiles are from 'd' or 'e'

c n = 2 ⋅ ( b n − 2 + c n − 2 + d n − 2 + e n − 2 ) ,

since there are two ways of ending 'c' and the previous tiles can be from any of 'b', 'c', 'd' or 'e'.

With similar reasoning,

d n = 2 ⋅ ( c n − 2 + d n − 2 + e n − 2 )

e n = 2 ⋅ ( b n − 3 + c n − 3 + d n − 3 + e n − 3 )

Initial 3 values for n = 1,2,3 are: b 1 = 1 , b 2 = 0 , b 3 = 2

c 1 = 0 , c 2 = 2 , c 3 = 2

d 1 = 0 , d 2 = 2 , d 3 = 0

e 1 = 0 , e 2 = 0 , e 3 = 2

On calculating the recurrence, we find the first 8 values of a n to be

{ 1 , 4 , 6 , 2 0 , 3 8 , 1 0 4 , 2 2 0 , 5 5 6 }

∴ a 8 = 5 5 6

As an aside, we can also obtain from the sequence:

f n = 4 f n − 2 + 2 f n − 3 + 2 f n − 4 + 4 f n − 5 with

f 0 = 1 , f 1 = 1 , f 2 = 4 , f 3 = 6 , f 4 = 2 0

and the generating function:

G ( z ) = 1 − 4 z 2 − 2 z 3 − 2 z 4 − 4 z 5 1 + z

The generating function can be used to obtain the following asymptotic form:

a n ∼ 0 . 5 8 1 1 8 9 4 0 5 1 8 2 5 9 8 ⋅ 2 . 3 4 9 8 1 5 3 1 5 7 1 9 5 0 n

We will call the tiles of type A in various orientations different names according to roughly how it looks: L, R, 7, and J (for rotations of 0 ∘ , 9 0 ∘ , 1 8 0 ∘ , 2 7 0 ∘ clockwise respectively; the name for R comes from the lowercase r).

Let a n , b n , c n be the number of ways to tile a 2 × n board such that the first column contains respectively two, one, zero squares covered by a tile of type A. Note that the total number of ways to tile a 2 × n board is then a n + b n + c n . We begin by initializing as follows:

- a 1 = b 1 = 0 ; there's not enough space to extend any tile of type A there.

- c 1 = 1 for obvious reasons.

- a 2 = 2 and b 2 = 2 can be brute-forced.

- c 2 = 0 ; if the first column doesn't have any tile of type A, the second column is forced not to have any tile of type A either and so violates the condition that no three tiles of type B can be replaced by a tile of type A.

- a 3 = 2 . After putting an L-tile on the first column, the remaining space needs to be filled with a 7-tile (not tiles of type B because they can be replaced); similarly, after putting an R-tile on the first column, the remaining space needs to be filled with a J-tile.

- b 3 = 2 . After putting a 7-tile, the remaining space is not enough of any tiles of type A. Similar for a J-tile.

- c 3 = 2 . After putting two tiles of type B on the first column, both squares in the second column needs to be filled with a tile of type A, so only an L-tile or an R-tile works.

Now we begin the recursion.

Sequence a : WLOG put an L-tile on the first column; later we will multiply the result by two to count where the first column has an R-tile instead. Now there are two cases:

- Case 1: The second column's empty space is filled with a tile of type A.

Then it must be a 7-tile, filling the second and third columns. The rest is a free 2 × ( n − 3 ) board, so there are a n − 3 + b n − 3 + c n − 3 ways to fill the rest.

- Case 2: The second column's empty space is filled with a tile of type B.

Then the third column cannot be tiled with two squares of type B. But in all other cases, the third column is free. So there are a n − 2 + b n − 2 ways to fill the rest (either one or two squares in the third column are of type A, so it's the sum of b n − 2 and a n − 2 ).

In total, a n = 2 ( a n − 3 + b n − 3 + c n − 3 + a n − 2 + b n − 2 ) .

Sequence b : WLOG put a 7-tile on the first column; later we will multiply the result by two to count where the first column has a J-tile instead. It's obvious that the rest is a free 2 × ( n − 2 ) board, so b n = 2 ( a n − 2 + b n − 2 + c n − 2 ) .

Sequence c : The second column cannot have any tile of type B, so the remaining 2 × ( n − 1 ) board must be tiled with two squares of type A in its first column; aka c n = a n − 1 .

Just solve the resulting system of recursions to get a 8 = 2 5 2 , b 8 = 2 0 8 , c 8 = 9 6 , and so the number of ways to tile a 2 × 8 board is a 8 + b 8 + c 8 = 5 5 6 .

Consider ways to tile a 2 × n grid under the problem's restrictions where (a) none of the rightmost two squares are tiled with B; (b) one is; or (c) both are. Let there be a n , b n , c n ways respectively.

For each configuration for n ≥ 4 , find its rightmost "fault line", i.e. a vertical line along which we can cut the configuration into a smaller configuration plus a few blocks. We'll list all the possibilities to arrive at a set of three recurrences.

(a)-type configurations must end in piece A with its missing corner facing inward, but that piece A could form a 2 × 2 block with another B or a 2 × 3 block with another A block. In either case, the fault line is immediately next to the blocks, and the added pieces can be flipped vertically in 2 orientations. The first case yields 2 ( a n − 2 + b n − 2 ) possibilities, since we can't extend a smaller (c) configuration or our B block would form an L-shape with the smaller configuration's B squares, while the second case yields 2 ( a n − 3 + b n − 3 + c n − 3 ) possibilities, since the smaller configuration touches two square of an A-block and no banned L-shapes can arise.

(b)-type configurations must have a piece A with its missing corner facing outward, filled with a piece B; again no banned L-shapes can arise with the smaller configuration to its left, so this can be tacked onto any smaller configuration, and again the added pieces can be flipped vertically for two configurations.

(c)-type configurations just end in two pieces B. They cannot touch any B-pieces, so the smaller configuration can only be type (a), and there is only one orientation.

This analysis gives us these recurrences:

a n = 2 ( a n − 2 + b n − 2 + a n − 3 + b n − 3 + c n − 3 )

b n = 2 ( a n − 2 + b n − 2 + c n − 2 )

c n = a n − 1

Obviously we can get rid of all the c n simply by substituting. Getting rid of b n is a bit trickier, but doable: from smaller recurrences we get

2 b n − 2 = 4 ( a n − 4 + b n − 4 + a n − 5 )

2 b n − 3 = 4 ( a n − 5 + b n − 5 + a n − 6 )

2 a n − 2 = 4 ( a n − 4 + b n − 4 + a n − 5 + b n − 5 + a n − 6

and when we substitute these into a n 's original recurrence, all the b i terms cancel; we get a n = 4 a n − 2 + 2 a n − 3 + 2 a n − 4 + 4 a n − 5 .

To deal with this recurrence, of course we want to derive a closed-form expression a n = k 1 r 1 n + k 2 r 2 n + k 3 r 3 n + k 4 r 4 n + k 5 r 5 n , where the r i are distinct roots of the polynomial x 5 − 4 x 3 − 2 x 2 − 2 x + 4 . Unfortunately this polynomial, being a quintic with no rational roots, is probably not going to be solvable by radicals. Oh well, we can do it numerically and hope that the error won't be too large, since we're only looking for terms up to around n = 8 .

So, we solve for roots numerically and find approximate values:

r 1 ≈ − 1 . 5 9 6 5 8 2 4 0 4 6 7 2 2 0

r 2 ≈ − 1 . 2 1 3 9 3 3 8 0 7 9 5 8 8 4

r 3 ≈ 2 . 3 4 9 8 1 5 3 1 5 7 1 9 5 1

r 4 ≈ 0 . 2 3 0 3 5 0 4 4 8 4 5 5 7 6 8 − 0 . 9 0 8 4 2 3 1 7 8 1 5 3 1 8 5 i

r 5 ≈ 0 . 2 3 0 3 5 0 4 4 8 4 5 5 7 6 8 + 0 . 9 0 8 4 2 3 1 7 8 1 5 3 1 8 5 i .

Solving for the recurrence coefficients with the first few terms yields

k 1 ≈ 0 . 2 2 2 6 4 6 5 5 8 5 4 0 9 2 2

k 2 ≈ 0 . 1 9 5 3 8 8 5 1 2 0 0 5 8 5 6

k 3 ≈ 0 . 2 6 0 0 2 0 1 8 8 2 8 7 6 6 9

k 4 ≈ 0 . 1 6 0 9 7 2 3 7 0 5 8 2 7 7 6 − 0 . 0 5 0 9 1 0 8 7 5 1 9 9 2 6 8 8 i

k 5 ≈ 0 . 1 6 0 9 7 2 3 7 0 5 8 2 7 7 6 + 0 . 0 5 0 9 1 0 8 7 5 1 9 9 2 6 8 8 i

So now we can evaluate a n = k 1 r 1 n + k 2 r 2 n + k 3 r 3 n + k 4 r 4 n + k 5 r 5 n very easily. To finish, we need to express b n and c n in terms of a i s. After more algebra we get b n = 2 a n − 2 a n − 1 − 2 a n − 2 + 2 a n − 3 − 4 a n − 4 . Of course, our original recurrence for c n works just fine.

Our final answer is therefore a 8 + b 8 + c 8 = 3 a 8 − a 7 − 2 a 6 + 2 a 5 − 4 a 4 . Evaluating our closed-form approximation for these a n yields 555.999999999998. Obviously the actual answer is an integer (in fact, even since reflecting a solution about its long axis is an involution with no fixed points), so the answer is very likely to be 5 5 6 .

Let f ( n ) be the number of ways to tile a 2 × n grid and let g ( n ) be the number of ways to tile a 2 × ( n + 1 ) grid without one of its corners.

It is then not hard to come up with the recursions

f ( n ) = 2 f ( n − 2 ) + 2 g ( n − 2 ) + 2 g ( n − 3 ) and g ( n ) = f ( n − 1 ) + 2 f ( n − 2 ) + 2 g ( n − 2 ) .

It is easy to calculate that f ( 0 ) = 1 , f ( 1 ) = 1 , f ( 2 ) = 4 and g ( 0 ) = 1 , g ( 1 ) = 1 , g ( 2 ) = 5 , and from there it is easy to compute that f ( 8 ) = 5 5 6 .