Why auroras happen at the poles

The charged particles from solar eruptions hit Earth mainly around the North and South poles (and cause auroras ). This is because our Earth is similar to a big magnet. The Earth generates a magnetic field and this magnetic field funnels the charged particles towards the poles. In order to see an example of this funneling, we can think of the following problem:

Consider each magnetic pole separately (so there's only one pole in the problem). The magnetic field near a single pole is B = k r / r 3 = k r ^ / r 2 where r is the radial vector point of the pole and the point of interest and r ^ = r / r is the radial unit vector. The sign of k is opposite for the North and South poles. If there's an electric charge moving in that magnetic field, its trajectory is on a surface of a cone, i.e. a big funnel. Find the vertex angle (the angle between the axis and a line on the surface of the cone) in degrees with these given initial conditions: the distance between the charge and the pole is r = 1 m and the velocity vector of the charge is v = 2 m/s perpendicular to the line connecting the pole and the charge. We will consider a north pole and so let k = 3 T ⋅ m 2 . The charge of the particle is q = 4 C and the mass is m = 5 kg .

Details and assumptions

- Hint: For anyone who has not taken electromagnetism yet, the force on the charge particle is given by the Lorentz force law: F = q v × B .

The answer is 39.81.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

4 solutions

Thank you Josh for the solution! I liked the way you have presented it without involving too much of maths. :)

Log in to reply

Thanks Pranav, I am glad I could bring some small amount of joy into your life. One day I hope to be able to submit a word-less, equation-less, image-only solution in your honor.

Actually,I can't understand THIS...😐...because I'm only in 2nd Grade...but I've already been bullied several times, so...please don't bully me😞

What would it mean if we saw an actual magnetic monopole in nature?

Log in to reply

We would have:

(a) the concept of magnetic charge,

(b) according to Dirac, the reason why electric charge is quantised,

(c) to rethink last week's Brilliant question which relied on the formula ∇ ⋅ B = 0 , which would no longer be true,

More seriously than editing a Brilliant question, we would need to rethink Maxwell's Equations. That's enough to start with!

this PROB doesn't deserve to be level 5

Josh, what software do you use to make such nice images in your solutions?

Log in to reply

I have a pretty low-tech operation going for the images. I use Apple's Keynote (the equivalent of PowerPoint) to organize everything and to draw the shapes and arrows and then I use LaTeXiT (http://www.chachatelier.fr/latexit/) to generate the mathematical symbols. I set LaTeXiT to font size 70 so that the symbols don't get pixelated in the image.

You seem to be assuming that the axis of the cone is pointing along the axis of rotation of the Earth - at least I presume so, since you have chosen a preferred z direction. This need not be the case; the direction of the axis of the cone depends on the original position and angular momentum of the particle, and finding that axis is the main problem.

Log in to reply

Hi Mark, thanks for bringing this up. I didn't mean to suggest that z ^ was the line going through the North pole and the center of the Earth. I only meant for it to be the axis of rotation that the magnetic field gives to the charged particle. As you say, the orientation of the axis is dependent on the details. I set out simply to calculate the vertex angle of the cone, leaving the angle of the axis relative to the Earth unspecified.

Perhaps it is poor form for me to calculate in spherical coordinates at the same time that I use an artifact of the cylindrical coordinate system to label the axis.

LOL.. even here I see a statement "Lorentz force is balanced by centrifugal force." What has happened to 'brilliant' guys?

Log in to reply

Please keep comments on Brilliant constructive. If you disagree with a physics point of one of the solutions, please explain why in a detailed way. This will improve discussion as everyone goes back and forth. Simply saying something is wrong, or using language like "LOL", which implies you are laughing at others on Brilliant, does not meet the standards for a valid comment. Nor is it how mathematicians and scientists work. We are required to defend our statements with logical analysis and our Brilliant members will be held to that same high standard (with some flexibility of course since most of our users are young and just learning their way in science and math).

Log in to reply

Yes.. I agree.. By the way.. we are already discussing the point in discussions.

If you work in a rotating reference frame, there is a "centrifugal force." Sometimes it is more convenient and intuitive to use it than having a centripetal acceleration. However, in general, yes, there is no true "centrifugal force."

I agree with the spirit of a campaign like this (to demand correct solutions) but in this case I don't see the point. Yes, a centrifugal force is an artifact of rotating reference frames, but guess what! If we move to a rotating reference frame, the "centrifugal force" is just as useful as if we'd insisted on the more puritanical program of identifying the central force as giving rise to a circular motion. No wonder then that in performing calculations for a physics and math puzzle site, one might resort to calculating devices that end in the same place as the orthodox analysis! Xkcd has made the point:

Xkcd

Xkcd

And here is Lubos making the same point: Lubos Motl discussing rotating reference frames

I would kindly ask you to identify a situation whereupon making a transformation into a rotating reference frame, and inserting the required fictitious forces, one goes awry in their analysis? Reference frames, inertial and non-inertial are used all over physics to calculate and there's no harm in using them.

@David Mattingly sir,why is the gravitational acceleration being not taken into consideration here,I considered that and the angle turns out to be much lesser than 40°,kindly elucidate

Log in to reply

Well, if we assume that the pole is at the centre of the earth, so that the full equation of motion is m r ¨ = r 3 q k r ˙ ∧ r − r 3 G M m r then, since the key quantity to calculate is r ∧ r ¨ (see my aged proof) we see that the gravitational attraction term cancels out when we take the vector product, and hence the same vector p is still constant, and we still have r ⋅ p = q k r . Thus p still defines the axis of the cone, and the semivertical angle is unchanged. Of course, the gravitational term will affect the trajectory of the particle on the surface of the cone, but...

Of course, in reality, the pole is not located at the centre of the earth, and so the gravitational pull will not act radially to the pole. This will make the equations very unpleasant to solve, and anyway the question does not give us information about the location of the poles within the earth!

For that matter, the real charged particles forming auroras have very small mass (unlike the test particle in this problem), and so I suspect that gravitational forces can be regarded as negligible in the real-world case.

Love this question

Hi, quick question: why is it that Fc cos theta = Fb and not Fb cos theta = Fc? If I were to look at it in the lab frame, shouldn't the argument be that the Lorentz force provides the centripetal force required for circular motion? After all, isn't the Lorentz force the one both resulting in circular motion and causing it to move in a cone?

Let the monopole be at the origin ( 0 , 0 , 0 ) , the charge at ( 0 , r , 0 ) with a velocity of ( v , 0 , 0 ) at the start. The force is ( 0 , 0 , ( q v k ) / r 2 ) , and hence acceleration is ( 0 , 0 , ( q v k ) / ( m r 2 ) ) . At time = dt, the velocity of the charge will be ( v , 0 , ( q v k d t ) / ( m r 2 ) ) and the average velocity of the charge in this time will be ( v , 0 , ( q v k d t ) / ( 2 m r 2 ) ) . Hence the position at time = dt will be ( v d t , r , ( q v k d t 2 ) / ( 2 m r 2 ) ) . The distance from the origin approximates to r + v 2 d t 2 / 2 .

Hence points B : ( v d t , r , ( q v k d t 2 ) / ( 2 m r 2 ) ) and A : ( 0 , r + v 2 d t 2 / 2 , 0 ) are both on the cone the charge moves on and equidistant from the origin. By symmetry, C : ( − v d t , r , ( q v k d t 2 ) / ( 2 m r 2 ) ) is also on the cone and equidistant from the origin.

The circumradius of isosceles triangle A B C is given by R = A B 2 / ( 4 A B 2 − B C 2 ) 0 . 5 . This is easily provable using similar triangles which I shall not show here due to a lack of diagrams. Using Pythagoras theorem, A B 2 = v 2 d t 2 + ( ( q v k d t 2 ) / ( 2 m r 2 ) ) 2 B C 2 = 4 v 2 d t 2 . Substituting the above into the equation for R , we have R = 1 / ( 1 + ( ( q k ) / ( m v r 2 ) ) 2 ) 0 . 5 . The angle of the cone is a r c s i n ( R / ( r + v 2 d t 2 / 2 ) ≈ a r c s i n ( R / r ) = 3 9 . 8 d e g r e e s .

We have: m d v = F d t = q v × B d t = q d r × B

Therefore, r × d v = m q r × ( d r × B ) .

Since B = r 3 k r , we have:

r × d v = m r 3 q k r × ( d r × r )

= m r 3 q k [ ( r . r ) d r − ( r . d r ) r ) ] .

Since r . r = r 2 and r . d r = d ( r 2 ) = d ( r 2 ) = r d r , we have:

r × d v = m r 3 q k ( r 2 d r − r d r r )

= m q k ( r d r − r 2 d r r )

= m q k d ( r r ) .

We also have: d ( r × v ) = d r × v + r × d v

= d t v × v + r × d v = r × d v .

Therefore, m q k d ( r r ) = d ( r × v ) .

Therefore, m q k r r = r × v + C where C is a constant vector, as in the figure below.

image

image

We know that the magnitude of vectors m q k r r and C is constant and m q k r r ⊥ r × v . Therefore, the magnitude of vector r × v is constant and the shape of the "triangle vector" is constant.

Therefore, angle θ between r and C is constant. This implies that the trajectory of the charge is on a cone with tan θ = q k m ∣ r × v ∣ = q k m r 0 v 0 .

Therefore, θ ≈ 3 9 . 8 1 ∘ .

Dinh, can you please explain why you take the cross product of r and d v ? Sorry if there is a obvious reason behind this but I honestly don't see it.

Thank you.

Log in to reply

Thanks for your comment.

First, when I see the prompt from the problem that the charge's trajectory is on a surface of a cone, I know that r or r r must have a connection with a constant vector along the axis of the cone as the angle between them is constant. Since the derivation of any constant vector will be 0 , I take the derivation of r r , which is r 3 r 2 d r − r d r r . The numerator can be notice as r × ( d r × r ) , so I try calculating the cross product of r and d v , which in turn leads to r × ( d r × r ) .

Sorry because the sequence in my solution is not the same as that in my thinking, but I thought the sequence in my solution would be more spontaneous

Another way to look at it is to write τ = r × F = d t d L instead of F = m a .

Great solution! ⌣ ¨

Note that d t d r ^ = = = d t d ( r − 1 r ) = r − 1 r ˙ − r − 2 r ˙ r r − 1 r ˙ − r − 3 ( r ⋅ r ˙ ) r = r − 3 [ ( r ⋅ r ) r ˙ − ( r ⋅ r ˙ ) r ] r − 3 r ∧ ( r ˙ ∧ r ) Since the equation of motion for the charged particle is m r ¨ = q r ˙ ∧ B = r 3 q k r ˙ ∧ r we deduce that q k d t d r ^ = m r ∧ r ¨ = m d t d ( r ∧ r ˙ ) and so the vector p = q k r ^ − m r ∧ r ˙ is constant, and since p ⋅ r = q k r we deduce that the particle moves on a cone with axis pointing in the direction of the vector p , and with semi-vertical angle α , where q k = p cos α .

Since the initial velocity is perpendicular to the initial radial vector, we deduce that cos α = q 2 k 2 + m 2 r 0 2 v 0 2 q k where r 0 is the initial radial distance and v 0 is the initial speed. In our case, this gives α = 3 9 . 8 ∘ .

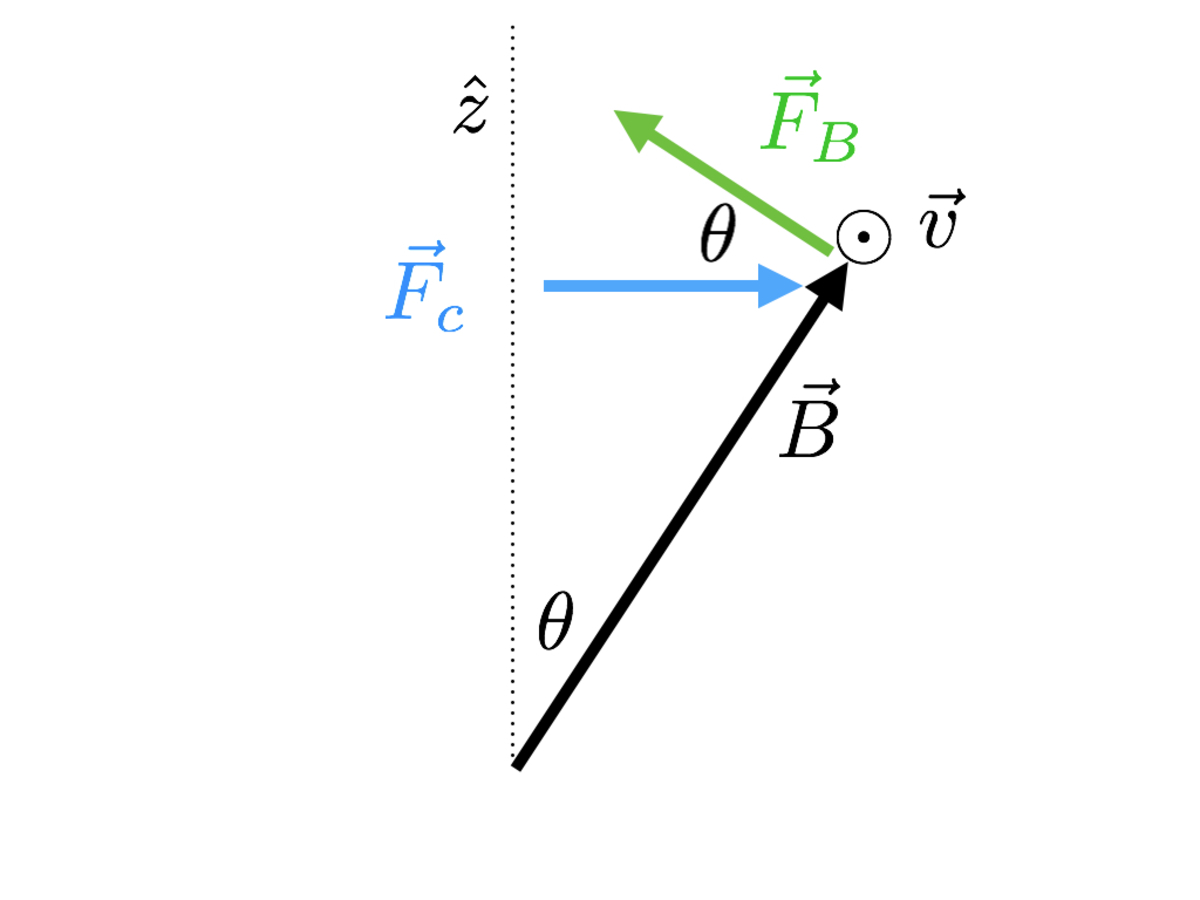

A magnetic field can rotate the direction of the velocity of an isolated charged particle but cannot alter the magnitude. This is because the magnetic field can only apply force that is perpendicular to the path of the particle. It follows that a magnetic field can do no work on an isolated charge. We can see this in our case by applying the right hand rule:

With the velocity v coming out of the page, and the magnetic field pointing along the radial vector, their cross product makes a vector that points up and towards the z -axis, as indicated by the green vector in the diagram above. In effect, the field at the North pole cannot move the charged particle from the line that's generated by extending the radial vector because such a movement would change r without changing the velocity, leading to an increase in the energy of the system, meaning that the magnetic field performed some work on the particle. The particle must therefore stay on the surface of the cone, that's generated by revolving the radial vector about the z -axis, as the problem claims.

Rotating in a curved path gives rise to a centrifugal acceleration, shown as the blue arrow in the diagram below:

Were the magnetic field in this problem a vertical one, the centrifugal force could be balanced perfectly by the Lorentz force, leading to a circular path. However we've shown that the magnetic field at the pole keeps the charged particle on the conical surface, therefore the Lorentz force only balances the component of the centrifugal force that's projected along the direction of the Lorentz force:

Putting this in concrete terms, the component of the centrifugal acceleration vector F c along the direction of the Lorentz force is F c cos θ .

The centrifugal acceleration is given by the usual form r ′ v 2 .

However, we're given the straight line distance from the particle to the pole, not the perpendicular distance, therefore r ′ = r sin θ and the centrifugal acceleration is a c = m F c = r sin θ v 2 .

Altogether, the component of the centrifugal acceleration that's along the direction of the Lorentz force is given by a c cos θ = r v 2 sin θ cos θ .

Now, the Lorentz acceleration is given by m F B = m q v × B = m r 2 q v k .

Equating this with the component of the centrifugal acceleration perpendicular to the surface, we have:

r v 2 sin θ cos θ tan θ = m r 2 q v k = k q m r v

or

θ = tan − 1 ( k q m r v )

Using the parameters provided, we have θ = tan − 1 3 × 4 5 × 1 × 2 = tan − 1 6 5 ≈ 4 0 ∘ .