Zap, I feel smarter!

Electricity and Magnetism

Level

1

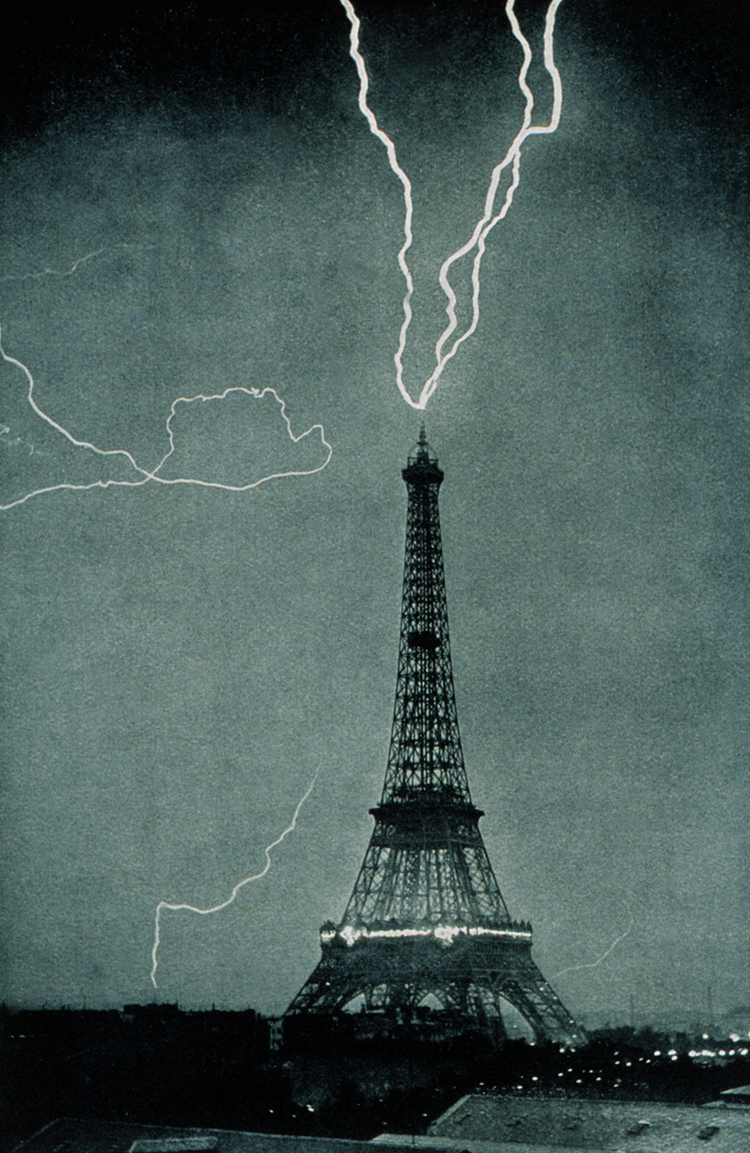

This lightning strike provides evidence that

This lightning strike provides evidence that

Air is always a perfect insulator.

Iron is an excellent conductor.

The earth is a bad conductor.

Hot weather is required for lightning.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

First of all, lightning doesn't only strike the Eiffel Tower. Here is a .gif of Paris during a lightning storm, demonstrating that lightning does hit all over the city.

In any case, the Eiffel Tower, and many other modern buildings are equipped with lightning rods, which are iron rods placed on top of buildings, and have a low resistance conducting path to the Earth. When lightning discharges from cloud to ground, and approaches the vicinity of a lightning rod, the strong electric field from the cloud and bolt induce a rush of positive charge into and out from the lightning rod. This forms an induced bolt called a positive streamer which rushes up toward the bolt.

In general, many such streamers can form, and whichever intercepts the incoming bolt will form a conducting path to the ground. If the streamer from the lightning rod is the one to connect, the massive charge from the bolt can be safely discharged through the low resistance rod, instead of through buildings, trees, or living creatures. The idea with lightning rods is to place them as high as possible above nearby structures, so that their streamer is most likely to intercept the lightning. They should also be made from good conductors.

That the lightning bolt hits the Eiffel tower at the top (at one of its lightning rods) demonstrates that iron (Fe) is an excellent conducting material.