Area of a Circle Part 2

In the first part, we divided a circle into infinitely many rings to attempt to find the area. We now have many lines of increasingly smaller length. But how can we answer the question of turning these lengths into an area?

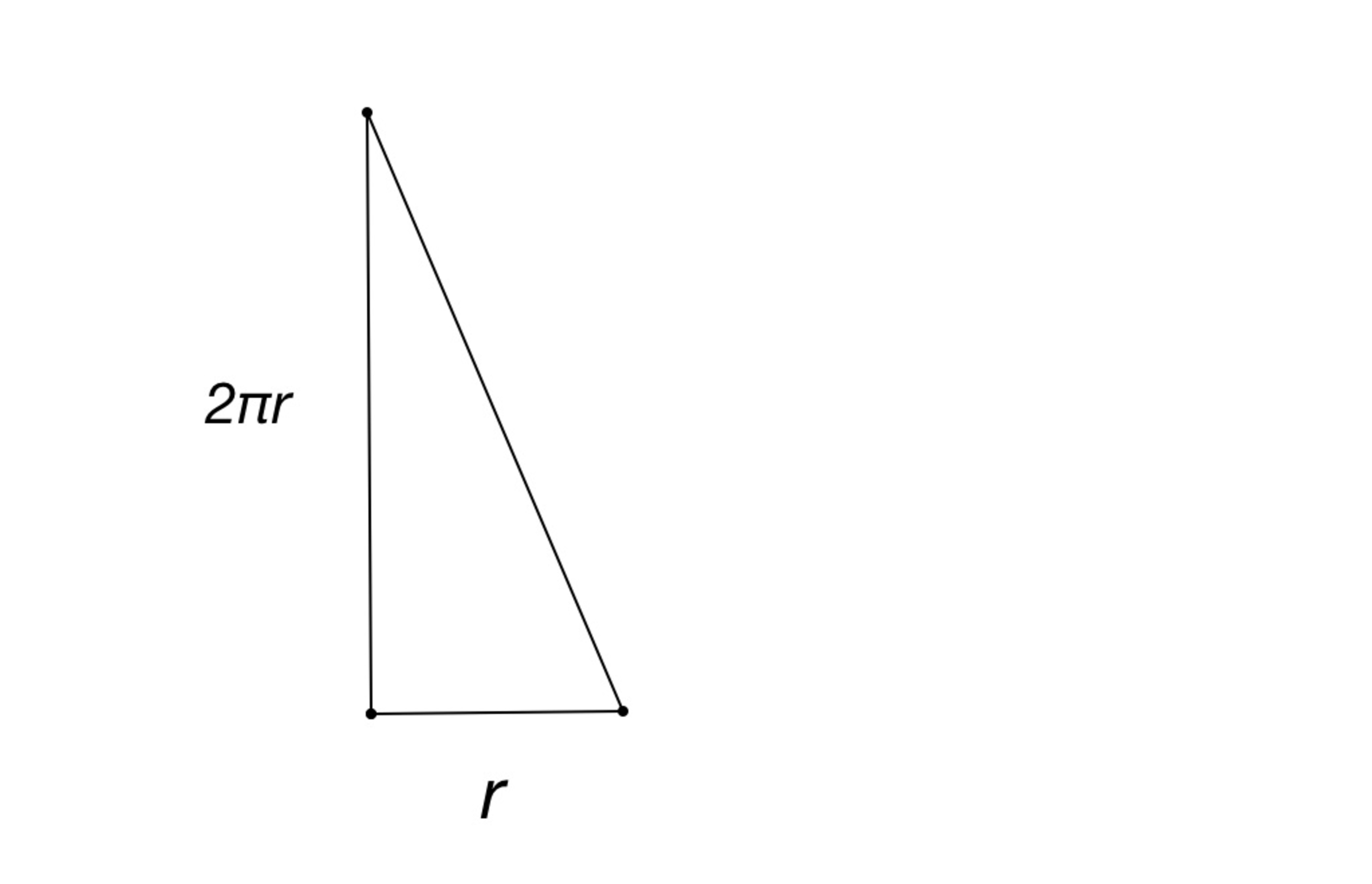

Let's begin by thinking about these rings laid out as lines. The first line is the circumference, with length . If they are all laid out with one end at equal height as the others, then the other end of each line will be shorter by a certain amount compared to the previous one. Since the "radius" of each of these rings is shorter than the last, the circumference of each ring, or it's length, is shorter, all the way down to the point in the center of the circle. This gradual decrease in line height starts to look line a line itself. Now, with enough lines or rings laid out in this way, the whole thing starts to resemble a shape.

A triangle, to be exact. The triangle's height is the circumference , and the base is the radius , as we took rings from the farthest reach of the radius to the center.

Now, we simply use the formula for a triangle's area, . Substituting in our values we get:

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

This is awesome! Never thought of it like this... but you have to be careful. When dealing with axiomatic properties and postulates, you can't prove a postulate with that postulate. For example, I shouldn't try to use the Pythagorean theorem to prove the Pythagorean theorem :P. The reason I am addressing this in this case is because if you look at the proof that the area formula is correct, it is based on the circumference formula. But still, great job!

Log in to reply

Yea I understand. Thanks