Dissecting Hinged Dissections

Polygons of equal area can be cut up into identical sets of smaller pieces. Amazing, right?

A beautiful new result is that this is also true of hinged dissections, like in the gif. Here’s the math behind the beauty, co-developed by longtime Brilliant user Scott Kominers.

Dissection of 2 polygons

Before we look at a hinged dissection, let's first consider the much simpler case of dissecting two polygons with equal area, where we want to cut them up smaller pieces which allows us to rearrange one polygon into the other. We present the main ideas, along with a quick sketch of the proof:

With these ideas, we can prove that it is possible to dissect 2 polygons of equal area:

Proof of dissection: The goal is to dissect a polygon of area into a square of side length . Then by claim 1, any 2 polygons of equal area can be dissected into identical pieces.

Suppose we have a polygon of area . We triangulate it into smaller pieces (Claim 2), and dissect each of them into a rectangle (Claim 3), which we then dissect into individual squares square (Claim 4). We combine these squares iteratively (Claim 5) to obtain a single square of side length . Hence we are done.

Hinged dissection of 2 polygons

Now that we understand how dissections amongst polygons work, let's consider having hinged dissections, in which the vertices of the pieces are connected to each other in the same way, which would restrict the possible movement of the pieces. For example, while the image in claim 3 immediately allows for a hinged dissection as indicated by the arrows, the images in claim 4 and 5 do not. We present the main ideas, and the proof of these claims is available in the paper.

Given a hinged figure, define the incidence graph which is constructed by placing a vertex at each piece and hinge, and 2 vertices are connected by an edge if one vertex represents a piece and the other represents a hinge on the piece.

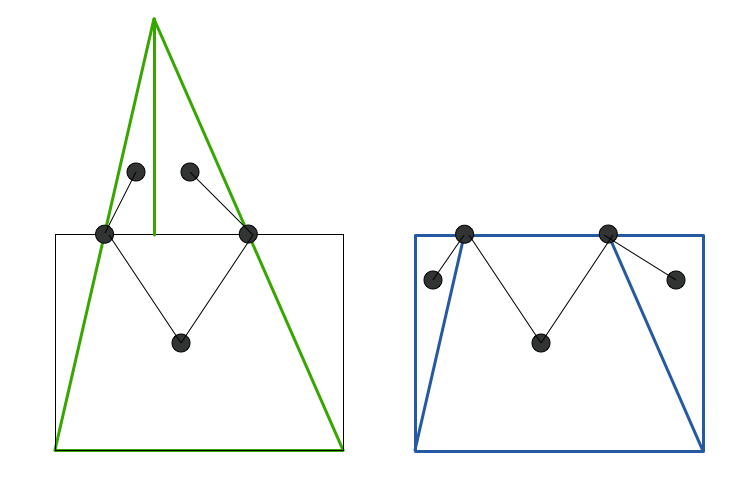

Incidence graphs of hinged dissections in claim 3

Incidence graphs of hinged dissections in claim 3

Claim 6. Given a hinged figure, if the incidence graph is a tree , then for any partition into subtrees and , are able to move rooted subtrees using subdivisions and shift to any part of to obtain a new incidence graph .

Example of how to move along a single edge

Claim 7. Given any hinged figure , there is a subdivision such that all valid configurations of are reachable by a continuous non-self-intersecting motion.

With these ideas, we can prove that hinged dissection of 2 polygons of equal area is possible:

Proof of hinged dissection: Start with any valid dissection of the polygons and which have identical pieces. Hinge the vertices of to form a tree, and do the same for . By claim 6, there is a common subdivision of hinged dissections. Using claim 7, there is a further subdivision that results in continuous, non-self-intersecting motion.

General case of polygons

To extend to polygons for dissection, we can simply overlay the dissections and move the numerous pieces around, as an extension of claim 1.

Unfortunately for hinged dissections, the main challenge is in figuring out a combination technique that works. This can be done using further machinery that refines the idea in claim 6 to more general structures. Complete details are available in the paper.

Points to ponder

- Is there an easier approach to the dissection of 2 polygons?

- Why does introducing hinges make the problem much more difficult?

- The claims work by allowing for a lot of extra pieces to allow for the movement of pieces. In the gif, the hinged dissection from an equilateral triangle to a square only uses 4 pieces as it doesn't follow the procedure outlined in the claims. Can we do better than 8 pieces for a hinged dissection from the square to the hexagon?

- In the gif, we used different hinged dissections to go from the triangle to the square then to the hexagon. Accordingly to the general case, there is a single hinged dissection that would work for all 3 shapes. Can you find it?

- The 3D case for dissections is known as Hilbert's third problem. We can dissect polyhedra of equal volume into identical parts if and only if they have the same Dehn invariant. What about hinged dissections?

Interested in geometry? Hinged dissections are pretty advanced, but our Outside the Box Geometry course has some fun problems that will get your creativity flowing.

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

Whoa, this is really cool... Thanks for posting... I love the graphic!

Calvin, do you know Sam Loyd? In his book, more mathematicals puzzles of Sam Loyd (Volumen ...), there is a problem (1.18). It is possible to cut the "crescent" moon in six parts to form a "perfect" Greek cross.

P.S.- Great graphics!

Log in to reply

Ah yes, I love Sam Loyd's books. Back when I was a teenager, I would devour them and very often got stumped on the problems.

Here is the problem from Amazon's preview:

Log in to reply

Yes, that is the problem, very good, what do you think about the solution?

Log in to reply

IIRC it was insane. I had no idea how to get it to 6 parts. I managed to do it with a lot of parts, by looking at the tessellation of the cross and of the crescent.

Log in to reply

I didn't do it . It was a madness... In your book, do you have the proof? I would made a copy or a picture or a photograph of the proof, but I can't publish it, here. For tessellations and mosaics, I recommend two examples, Escher and Alhambra de Granada .

PS.- If someone likes spanish guitar, listen to this Recuerdos de la Alhambra and the speed of his fingers at the right hand...

The .gif animation above reminds me how Sherlock solves cases using the method of loci.

Log in to reply

Just joining the meaningless pieces of the case to one meaningful conclusion.