Divisible by 7?

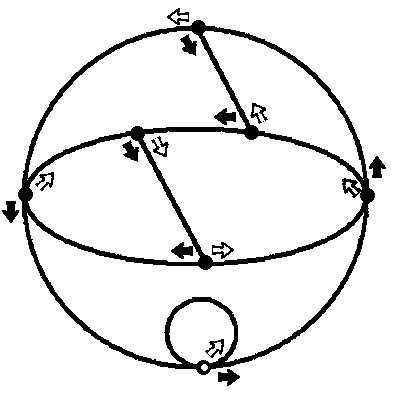

Last night, I was exploring the Internet, when I stumbled across a very cool diagram. It look like this:

With this graph, you can see what numbers are divisible by 7. Lets take the number 1234567. You would first start at the white node at the bottom. First move 1 black arrow, then 1 white arrow, then 2 black arrows, then 1 white arrow, then 3 black arrows, the 1 white arrows, and so on and so forth. For each digit number of black arrows you move, you move 1 white arrow. If you end up at the start, then it is divisible by 7. However number of black arrows away from the start you are is the remainder. Can someone prove this?

No vote yet

1 vote

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

I think i have figured out the proof.

So, starting from the starting point mark the junctions as 0,1,2,3,4,5,6. Note that every junction represents the number [mod7].

Now choose any number and start the procedure. Let your first digit is a. Follow the black arrow a times. You will currently be at a juction that represents a[mod7].

Now, if you have one more digit then you are asked to move in the direction of the correspondong white arrow.

These white arrows are so arranged that the corresponding white arrow takes you to the place a×10[mod7] (You can check it for all 7 cases.).

It means now you are at a0[mod7].

Now, if your next digit is b, you will , after moving b black arrows will reach at abmod[7] position.

This will continue and at any step you will be at the position that represents your current number [mod7].

By this, the working of this diagram is explained and using the same method I have made diagrams for divisibilty tests of 6,8 & 11.

Log in to reply

Awesome! Upvoted!

Another cool thing about multiples of 7 is that if you multiply the last digit by 5, and add it to the remaining number, it will always be a multiple of 7. For example:

84: 8 + 4×5 = 28 = 4×7

161: 16 + 1×5 = 21 = 7×3

And this does not only apply to multiples of 7. Take multiples of 13, for example. When the last digit is multiplied by 4, the sum of that and the remaining number will also be a multiple of 13. For example:

26: 2 + 6×4 = 26 (this kind of becomes a loop, but you get the point.

I have documented how this works for many numbers… (From what I have seen, it only occurs with some numbers)

3: Multiply last digit by 1 (3 * 3 = 10 − 1)

7: Multiply last digit by 5 (7 * 7 = 50 − 1

9: Multiply last digit by 1 (9 * 1 = 10 − 1)

11: Multiply last digit by 10 (11 * 9 = 100 − 1)

13: Multiply last digit by 4 (13 * 3 = 40 − 1)

17: Multiply last digit by 12 (17 * 7 = 120 − 1)

19: Multiply last digit by 2 (19 * 1 = 20 − 1)

The notes in parentheses are observations I have made. But can someone explain why?

Log in to reply

That's a nice observation. I will prove this for 7.

Let the given number be n=apap−1..........a0. This number is also given to be a multiple of 7.As the 'trick' involves only the last digit and the remaining number, let's reduce this whole number to ab where b=a0 and a=apap−1.........a1(mod7).

The algorithm is multipying b by 5 and adding it to a.

So, we will be left with the number

m=a+5⋅b and we are required to prove that m=0(mod7)

Now note that

10⋅m(mod7)=10⋅a+50⋅b(mod7)

=10⋅a+b(mod7) [because, 50=1(mod7)]

=ab(mod7)=0(mod7)

⇒10⋅m=0(mod7)

⇒m=0(mod7).

Hence proved.

On similar lines, you can also prove it for other numbers.

Log in to reply

Wow!!! Next time in math class, when my teacher asks me if 882 is divisible by 7, or if 912 is divisible by 19, I can say yes in an instant!!!

Log in to reply

Try this

Where did you learn about this? It is very neat

Wow! It's a great thing you even figured the whole trick . If I would have seen it somewhere on the net , I'd have thought it was something related to Physics and would have closed the tab :P

Can any of you guys create a diagram like this for testing multiples of 13 or 17 or 19 or any prime numbers greater than 5? It would be really cool!

Log in to reply

Here's one for 13. (I have used single arrow in place of black and double in place of white)

Log in to reply

And question: How do you come up with these pictures? Is there some sort of trick to it?

Log in to reply

There's no 'trick' to it, its just a application of 'remainders' or 'modulo arithmetic' and I have explained it all in a comment above namely "I think I have figured out the proof.........". Understand from there how the diagram of 7 is working and you will be able to make similar diagrams for any number. If you have any doubt in the explaination, do ask.

Log in to reply

ok thanks!