Fallacy of the Isosceles Triangle

Throughout the last of couple of weeks, we've been having some fun with geometrical fallacies. We've seen what makes them work and how to spot the wrong arguments that constitute the fallacious proofs. Today we're going to end the series with a classic geometrical fallacy; one that is possibly the most popular when it comes to geometric fallacies: the "proof" that all triangles are isosceles.

This fallacy has been attributed to Charles Dodgson who is better known as Lewis Carroll. Most people know Carroll as the author of the children's book, Alice's Adventure In Wonderland. But what some people don't know is Carroll was also a noted mathematician and logician who loved some recreational mathematics.

This post is going to be pretty much like the earlier ones. I first present you with the "proof". Then I ask you think about what went wrong and why. Finally I walk you through the steps and reveal the invalid argument. So let's get on with it!

Imgur

Imgur

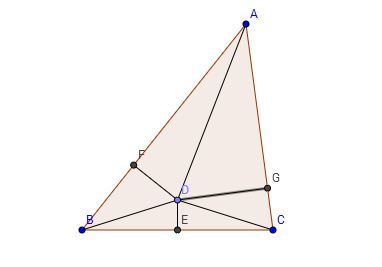

Let be a triangle. Draw the angle bisector of and the perpendicular bisector of . Notice that if they are the same line, is isosceles. If they are not the same line, they're going to intersect at a point. Let's call that .

Let be the midpoint of . and are the feet of perpendiculars from to and respectively. Join and .

Notice that and are congruent [SAS], because , and since they are equal to a right angle.

So, now we can write .

Triangles and are also congruent [AAS] as , [remember that was the angle bisector of ] and .

From that we can write

And .

Now we move on to triangles and .

From and and from the fact that and are right angles, we can conclude that triangles and are also congruent.

And that means .

Now add and together and see what happens.

That means is isosceles! How did that happen? You can use the similar arguments to prove and prove that all triangles are actually equilateral!

Now comes the slightly over-asked question: what went wrong? Go back to the steps and try to figure it out. Don't continue reading if you don't want to know the solution without giving it a shot.

I take it that you've thought about the fallacy for a while. Have you figured it out? If repeatedly talking about fallacies taught us one thing, it's this: drawing a sufficiently accurate picture always helps. And that advice isn't restricted only to fallacies like this. You can use this even while solving normal geometry problems. An accurate figure helps you make good educated guesses [for example, "the lines sure look like they're parallel, let's prove it! And that angle looks like a right angle. Can I prove it?...]. So, let's take a look at a more accurate picture:

Imgur

Imgur

This actually makes sense. The point is actually outside the triangle. We never proved where was. We only assumed [incorrectly] that it was inside. This also tells us that everything up to the last step was absolutely correct. The lengths were equal. The triangles were congruent as well. Even was correct. But the transition to the final step was not. We made an incorrect assumption that . If , , not . This is what made us arrive at a wrong conclusion.

So, there you have it! This is the last post of the geometric fallacies series. I hope you had as much fun reading the posts as I had writing them. And thank you for staying with me till the end. If you missed one or two posts, you can check out my feed here or try the #mathematicalfallacies tag.

Until next time!

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

That was it! The last post on the geometrical fallacies series! I hope you enjoy this one as well. Feel free to post any feedback in the comments section.

And thank you, thank you, thank you for staying with me.

Log in to reply

Your initial diagram can be made to look more convincing by drawing a triangle closer to isosceles. However, the accurate diagram would be harder to draw.

Other than that, great posts! I loved them.

This makes me want to post more, although I am pretty busy... :P

Log in to reply

Thanks, Daniel, for your kind words. It really does mean a lot!

And about making the diagram more convincing: if my triangle were any closer to an isosceles triangle, point D would be really close to BC. And people don't draw diagrams that accurately as well. Ask people to draw a diagram based on the instructions above and if they don't use compasses or rulers, they are going get a picture that is quite similar to mine, specially if you add the line "let the angle bisector of ∠A and the perpendicular bisector of BC intersect at D" [this psychologically influences them to assume that D is inside the triangle].

It's interesting that people are discussing about why the picture's wrong when the more important thing is why the argument's wrong. You don't have to draw pictures 100% accurately make geometric arguments.

Once again, thanks for your feedback! I appreciate it a lot! And I'm looking forward to your posts. Keep them coming :)

How do you think of such things , can you suggest me from where do I have to start?

Log in to reply

I believe he was sharing a well-known incorrect proof. I don't think he was the one who invented it.

Log in to reply

Yes, I think I mentioned that this fallacy's been attributed to Lewis Carroll.

Log in to reply

Sorry I commented here , I was reading all the notes of the set geometric fallacies one by one , i was astonished to see this fallacy - Are you inside or outside

Thanks

Cool!

I read your PDF on it in Bengali a month ago and figured out the mistake there instantly when I looked at the picture. The difference between that one and this one is that in that one, you bisected ∠A correctly, but did not point out the midpoint of BC accurately. So anyone could catch the mistake instantly. In fact, before reading the whole, I quickly did a GeoGebra check and found out that the point D is actually outside the triangle.

Comparing to that one, I like the picture in this one as you pointed out the midpoint of BC accurately, but did not bisect ∠A accurately. It's far more difficult to catch the mistake from bisected angle than from the midpoint.

And...... Great posts! I had fun!

Log in to reply

Where on earth did you read that!?

By the way, the point of this [and the other posts on fallacies] was not to find the mistakes in the pictures. The point was to find which arguments were invalid and learn that you should never ever assume anything without proof. You line of thought should be like this: "Yeah, the picture looks fishy, but then again you can't draw anything 100% accurately. So, what is wrong with the arguments presented?" Do you draw diagrams with compasses and rulers whenever you solve a geometry problem or do you just draw something that looks okay.

So, why am I saying this? I'm saying this to emphasize that the "proof" isn't wrong because the picture is wrong. The proof is wrong because we made an implicit assumption. Yes, the inaccurate picture helped us make that assumption but that is not what's wrong. I hope you understand this.

By the way, the picture from the pdf: that was from Wikipedia. So, that's Wikipedia's fault, not mine:)

"I present you wit the 'proof.'" Typo paragraph 3 :)

Log in to reply

It seems like I can't break the habit of making stupid typos. Thanks for pointing it out!

This is very interesting. But you don't give any proof or reason to support the fact that D is outside the triangle. The proof is actually an extension of the 'angle bisector theorem' which basically proves that the bisector will never cross the perpendicular bisector of the opposite side (unless it's an isosceles, in which case the angle bisector is also the perpendicular bisector).

asked me in kvpy interview