I recently stumbled across this great problem which is a must-try-to-solve problem if you want to practice your algebraic manipulation abilities. Αnd in case you are interested in advanced classical inequalities there are some useful identities it highlights such that ⎩⎪⎪⎪⎪⎨⎪⎪⎪⎪⎧ab+bc+ca=2(a+b+c)2−a2−b2−c2(a+b+c)3=a3+b3+c3+3(a+b)(b+c)(c+a)(a+b+c)(ab+bc+ca)=(a+b)(b+c)(c+a)+abca3+b3+c3−3abc=(a+b+c)(a2+b2+c2−ac−bc−ca)

However the subtle lie of the problem is that despite the numbers (a+b+c),(a2+b2+c2), (ab+bc+ca), (a+b)(b+c)(c+a), (a3+b3+c3) and (abc) are all real, it can be shown that for the given values it is impossible for all a, b and c to be real.

Now I need to focus your attention specifically in those 3 real numbers: (a+b+c), (ab+bc+ca), and (abc). Do they remind you anything? No? Anything related with polynomials?

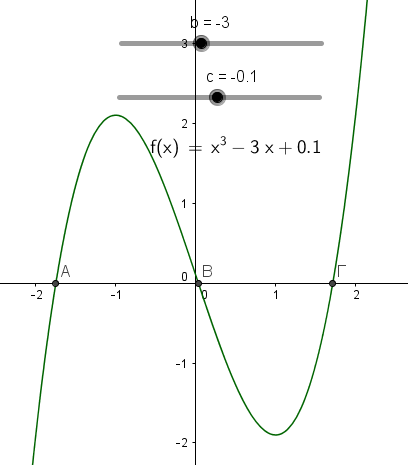

Well consider a third degree polynomial P(x)=(x−a)(x−b)(x−c) where a, b, c are its roots (either real or not). Then you can rewrite the polynomial as P(x)=x3−(a+b+c)x3+(ab+bc+ca)x−abc. So −(a+b+c), (ab+bc+ca), and −abc are the real coefficients of each term of a third degree polynomial!

I also though of Newton's Inequality (I'll try to explain it the best I can) which states that Sk−1⋅Sk+1≤Sk2∀ integers k∈(0,n) where Si represent the elementary symmetric polynomial divided by (in) and n is the number of variables.

Therefore for n=3 we obtain S0=1,S1=3x1+x2+x3,S2=3x1x2+x2x3+x3x1,S3=x1x2x3 where xi is a real number. Thus according to Newton's Inequality for k=2 it is x1x2x3⋅3x1+x2+x3≤9(x1x2+x2x3+x3x1)2(∗)

Now assume that P(x) has all its roots being real numbers. Then by substituting in (∗) x1=a,x2=b,x3=c we obtain abc⋅3a+b+c≤9(ab+bc+ca)2(∗∗)

If (∗∗) is not satisfied we can conclude that some of the roots are not real numbers.

Taking the values of the problem we can create the polynomial P(x)=x3−7x2+13x−89. Let all its roots be real numbers, then by Newton's Inequality it should be 89⋅37≤(313)2⇔1700≤0 Contradiction! Thus P(x) has two imaginary roots.

We can use this method of the ATTEMPT to determine the real roots of a polynomial, for all the polynomials of degree greater or equal to 3. For example for a fourth degree polynomial Q(x)=x4−(a+b+c+d)x3+(ab+bc+cd+da+ac+bd)x2−(abc+abd+acd+bcd)x+adcd if either one OR more of the following inequalities do not hold then some of its roots are not real. 1⋅6ab+bc+cd+da+ac+bd≤16(a+b+c+d)24a+b+c+d⋅4abc+abd+acd+bcd≤(6ab+bc+cd+da+ac+bd)26ab+bc+cd+da+ac+bd⋅abcd≤(4abc+abd+acd+bcd)2

(Generally if δ is the degree of the given polynomial then you are able to check (δ−1) inequalities)

Caution! If the inequalities hold then we cannot conclude that the roots of a polynomial are real.

My observation is that if at least one of the inequalities does not hold then the polynomial has imaginary roots :)

#Algebra

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

Hmmmm, even your 4th inequality needs to have a constraint of POSITIVE reals. (See the pdf again, page 2, Theorem 10).

Looking over your note again (especially the paragraph above) shows that you didn't realize that the roots must be positive real as well. So your paragraph should end with

Similarly, your last paragraph should be changed to

Overall, I think what you have (for identifying roots of cubic polynomials) is an eye-opener, which works well when it's applied alongside Descartes' Rule of sign. Thanks for teaching me something new!

In the meantime, I'm still working on polynomials of degree 4 and higher. I'll report back if I found something interesting.

On an unrelated note, your writeup is very long, yet it's very easily understood! Have you considered writing articles? I think you will be great at it.

Log in to reply

lol thanks, but in school writing articles was the worst for me :D

Anyway, I thought only Maclaurin's Inequality (between those two) holds for positive real numbers. But despite the fact that the fourth inequality derives from Newton's Inequality, it happens that it holds for all real numbers as well. Actually the inequality in question is the following 9(r1r2+r2r3+r3r1)2≥r1r2r33r1+r2+r3 which is equivalent with (r1r2+r2r3+r3r1)2≥3(r12r2r3+r1r22r3+r1r2r32), let r1r2=x,r2r3=y,r3r1=z then (x+y+z)2≥3(xy+yz+zx) which is true for all real numbers.

Note that the second inequality can be expressed as Newton's Inequality since it is S12≥S0S2 where S0=1, but holds for all real numbers too.

Update: In Wikipedia's page for Newton's Inequality it is mentioned that the inequality holds for all real sequences but I guess that either Wikipedia is not trustworthy or the writer of the pdf forgot to emphasize the difference in their attempt to gather the two inequalities (Newton's and Maclaurin's) together. The first seems more likely.

Log in to reply

You bring up some valid points. I did some research it most common search results shows contradicting constraints: some say "real numbers", some say "positive reals". I will find the root of this problem and I will keep you posted.

In the meantime, I couldn't really create any nice inequalities for the 4th degree polynomial, they all turn out to be very messy. I will continue my research in the following week.

Log in to reply

By the way for determining the positive roots of a polynomial we can use Maclaurin's Inequality (alongside Descartes' Rule of Sign as you've stated!). Consider a monic polynomial of degree n such that P(x)=xn+an−1xn−1+an−2xn−2+an−3xn−3…+a2x2+a1x+a0. Let P(x) have all its roots positive real numbers. Then the following should hold:

For even n:(1n)−an−1≥(2n)an−2≥3(3n)−an−3≥⋯≥n−2(n−2n)a2≥n−1(n−1n)−a1≥n(nn)a0

For odd n:(1n)−an−1≥(2n)an−2≥3(3n)−an−3≥⋯≥n−2(n−2n)−a2≥n−1(n−1n)a1≥n(nn)−a0 But think that the greater n is, the more useless the above gets, since "most" of the polynomials have negative or non-real roots too.

Really thanks for your help and your interest!

Actually I don't feel done with cubic polynomials. Let me show you my work so far:

Let the cubic monic polynomial P(x) and its depressed polynomial Q(x). If Q(x) has three real roots then so does P(x). Let Q(x)=x3−ax2+bx−c for some real a,b,c where a=0 have three real roots r1,r2,r3. Then we obtain a=r1+r2+r3,b=r1r2+r2r3+r3r1,c=r1r2r3. Applying twice Newton's Inequality (which in this cases holds for all real numbers) we get: S12≥S0S2⇔9(r1+r2+r3)2≥1⋅3r1r2+r2r3+r3r1⇔9a2≥b⇔a=0b≤0S22≥S1S3⇔9(r1r2+r2r3+r3r1)2≥r1r2r3⋅3r1+r2+r3⇔9b2≥3ac⇔a=0b2≥0(Not helpful at all) Thus we conclude that b should be negative for Q(x) to have all its roots real numbers. (Obviously since in other case Q(x) would be a strictly increasing function, therefore would have at most one real root.)

But this is not enough. By observing the graph of Q(x) and by "playing" with the values of b,c we can see that the variable c plays a crucial role in determining the number of real roots of Q(x). Actually for a fixed negative b, c should belong to an interval of the form [−k,k] (for some positive k) for Q(x) to have three real roots. In my unsuccessful attempts to find an inequality of the form c2≤k2 (or any inequality that determines the value of k), I used the cubic discriminant and concluded that the following inequality should hold Δ=−4b3−27c2≥0⇔4(r1r2+r2r3+r3r1)3+27(r1r2r3)2≤0(∗) My problem is that I cannot understand why (∗) holds for all real numbers given the conditions r1+r2+r3=0 and r1r2+r2r3+r3r1≤0.

In my unsuccessful attempts to find an inequality of the form c2≤k2 (or any inequality that determines the value of k), I used the cubic discriminant and concluded that the following inequality should hold Δ=−4b3−27c2≥0⇔4(r1r2+r2r3+r3r1)3+27(r1r2r3)2≤0(∗) My problem is that I cannot understand why (∗) holds for all real numbers given the conditions r1+r2+r3=0 and r1r2+r2r3+r3r1≤0.

But we can conclude that −2(3∣b∣)23≤c≤2(3∣b∣)23. :)

Log in to reply

I'm just letting you know that I haven't forgotten about this conversation. I got some errands that I need to take care of. I will come back to you soon (another week or two).

This is very nice! And here I am only thinking about Descartes' Rule of Sign...

Your Newton's inequality follows from another important classical inequalities. Here's the link for the interested users (page 2).

Let me see if there is any other additional insight. Will report back if I've found something else.

Log in to reply

I just realized that classical inequalities can be useful in determining the quantity of real roots of a polynomial. For example in a monic 2nd degree polynomial P(x)=x2+bx+c with real roots r1,r2 it is Δ≥0⇔b2−4c≥0⇔(2b)2≥c⇔(2r1+r2)2≥r1r2 which is (kinda) AM-GM.

I'm currently investigating the cubic equation x3−ax2+bx−c=0. If there are 3 real roots then the following inequalities should hold. ⎩⎪⎪⎪⎨⎪⎪⎪⎧a3≥27c since (r1+r2+r3)3≥27r1r2r3for ri≥0a2≥3b since (r1+r2+r3)2≥3(r1r2+r2r3+r3r1)b3≥27c2 since (r1r2+r2r3+r3r1)3≥27(r1r2r3)2for ri≥0b2≥3ac because of Newton’s Inequality I am also thinking how the above inequalities are connected with Cardano's Method.

Log in to reply

Here are some of my unfiltered thoughts after reading your comment. (not sure if any of them are helpful or not):

My first thought after reading your second paragraph is cubic discriminant. Not sure if you have thought about it....

And regarding Cardano's Method, I find it much easier to simplify the working if you depress the polynomial from the very beginning!

I think you're up to something fascinating; I will work on this even further during the weekends.

Log in to reply

I'm sorry but in the second paragraph of my comment, the 1st and the 3rd inequality should hold if the roots are positive real...Really thanks for your thoughts though!!! I'll check if the depressed polynomial helps more!

Awesome work!

This reminded me of my past attempt to find the maximum value and minimum value of abc with some constraints.

I am posting my work, if there is any mistake, please let me know thanks!

@Pi Han Goh @Chris Galanis

Log in to reply

I don't know weather it has been found before or not.

Log in to reply

It's a fairly common technique. That's similar to Calvin's comment in my solution.