Is 0.9999... = 1?

Hi everyone,

I really want to start a discussion on a topic: Is exactly equals to 1 or it is just an approximation?

Recently, I posted a problem and continuously users are reporting it as wrong.

Now I want to be sure about that . = or not?

I thought my brilliant friends will help me out.

Any proof in favor or in against will be appreciated.

I thought my brilliant friends will help me out.

Any proof in favor or in against will be appreciated.

Thank you.

No vote yet

1 vote

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

The problem with this issue is that we find it difficult to get out heads around limits of series. Since these can be pretty weird, that is forgiveable!.

Let us assume that the number a=0.9˙ exists. Since 0.999⋯9 (for any finite number of 9s) is less than 1, we can reasonably deduce that a≤1.

Suppose now that 0<b<1. If we consider the decimal expansion of b, we will eventually find a number after the decimal point which is less than 9. In other words, we will be able to write b<0.999⋯9, where the number on the right of this inequality has a finite number of 9s after its decimal point. Thus b<a.

In other words the number a is less than or equal to 1, but is greater than any number less than 1. This means that a must be equal to 1. In other words, if 0.9˙ exists, it must be equal to 1.

The only problem left is that of accepting that the number a exists in the first place. This is a nontrivial issue, and many mathematicians, starting with the ancient Greeks, have had problems with infinite limits. Consider such "paradoxes" as Zeno's paradox or the Achilles and the tortoise paradox.

If we are prepared to accept a mathematical system within which limits exist, then 0.9˙ will both exist and be equal to 1, and 0.3˙ will exist and be equal to 31. The existence of such limits is based upon what is called the Completeness Axiom of the Reals; while mathematicians might try to see what can be deduced in the absence of this Axiom, I would think that few disbelieve it.

It is interesting that students find the existence of 0.9˙=1 harder to accept than they do the existence of 0.3˙=31. Accepting that either of these numbers exists involves coping with the idea of an infinite number of entries in a decimal expansion; there is something about the fact that the identity 0.9˙=1 increases the digit before the decimal point that gets people agitated, while students at a very early age have few problems with 0.3˙=31. From a teaching point of view, therefore, observing that 3×0.3˙=0.9˙, and therefore that 0.9˙=3×31=1 is an argument which can content most students, at least until they can get to grips with the proper definition of the limit of a series.

Log in to reply

(Printer is on) hahaahahah! Just kidding!

You wrote what Otto Brestcher wrote up here in the solution discussion but in a much clearer manner!

Good read! I didn't think of the analogy between Tortoise paradox and 0.9=1.

Completeness Axiom of the Reals? Woah! First time hearing of about this! Good read! Your comments are always so valuable! Brilliant should always send me a notification wherever you post anything in Brilliant!!

Can you explain why this happens? Or why mathematicians disagree about this (Is it because most people can't grasp new concepts like the controversy over Cantor's theory)? Does this issue still occur? And why?

Log in to reply

It is not so much a case of mathematicians disagreeing about it; the Completeness Axiom (i.e. the existence of least upper bounds) is what defines the reals. Mathematicians can, however, be interested in determining how much can be deduced without assuming this Axiom. An increasing bounded sequence converges to its least upper bound; if we drop the Completeness Axiom, then we cannot have limits of any sequences except those which are eventually constant (and for which convergence is obvious). No limits means no calculus, and the whole field of Analysis goes down the tubes. What you are left with is mathematics that can be done within the rationals - Diophantine equations and the like. These are, of course, exceptionally rich fields of study.

It is interesting to note how Analytic Number Theory has found great usefulness of the real number system, and the machinery of analysis of real number, in the service of solving equations and problems about rational numbers.

In a similar manner, logicians are interested in what can be deduced if you remove Proof by Contradiction from your armoury (this is an example of what is called Constructivist Logic). This is important, since computers cannot prove by contradiction, and so results that can be proved without using Proof by Contradiction are essentially those that can be machine-proved

Log in to reply

I don't know much about this subject matter (of Completeness Axiom) until recently, so forgive me if I sound ignorant, but is it in any way similar to accepting/rejecting the Axiom of Choice? Because I'm more familiar with that area as compared to Completeness Axiom.

Can you explain to me why these mathematicians prefer to restrict themselves by not assuming this axiom? Because I don't see the benefit of it at all. Is it because they want to find a more elegant solution to the necessary questions? Or because they think that this Axiom is not rigorous (highly doubt it)? Or something else entirely?

From your entire first paragraph, it sounds to me that what you're saying is that some mathematicians prefer not to use Completeness Axiom simply because of they are merely asserting one's preference, no?

Wait, isn't proof by contradiction super duper important? Why are logicians interested in handicapping themselves by restricting themselves by not using that commonplace method? What's the point of all these? Is there a benefit to this restriction?

(Advertisement).

Log in to reply

The Axiom of Completeness of the reals has nothing to do with the Axiom of Choice, except that they are both Axioms! The Completeness Axiom says that any bounded nonempty set of reals has a least upper bound, something which is not true about rationals. The Axiom of Choice states that it is possible (essentially) to make uncountably many selections at the same time - if I have a collection of sets Sx, one for each real number x, the AofC says I can create a function f with domain R such that f(x)∈Sx for all x. This Axiom permits transfinite induction (induction on uncountable sets). Much high level mathematics would be impossible without this Axiom. However, it is still an Axiom, in that we have no proof that it is true. Mathematics with and mathematics without the AofC are both perfectly consistent; maybe one day someone will discover a subtle difference between what is possible in both systems which will determine which is true!

Mathematics is the business of investigating what is possible. It can be interesting to investigate what can be deduced if only some properties, or methods of argument, are assumed. That is why mathematicians study groups, for example. There are many cases where a number system is more complex than being just a group, but knowing its group-theoretic properties is nonetheless interesting. Alternatively, Algebraic Number Theorists can be quite happy studying the integers, and do not always need to think about the reals at all ( on the other hand, Analytic Number Theorists have found great value in real number theory in the study of integers).

As I said previously, if you are a computer theorist, you are not that fond of Proof by Contradiction, since your pet machines cannot use it. You are therefore extremely interested in what can be proved without it. Mathematical Logic, without Proof by Contradiction, is perfectly consistent and sensible; the only problem is that there are lots of elementary statements that are true, but cannot be proved, within it. Of course, Godel's Incompleteness Theorem proves that there are true, but unprovable, statements within any sufficiently complex system of logic. The difference is that we don't ever know in general which those statements are, whereas it is easy to find true statements which cannot be proved without Contradiction.

Log in to reply

Thanks for your immediate reply!

I spent some time last week to read up all these axioms again and to be honest, I don't fully grasp most of them. Maybe due to the extreme lack of exercises in the (only) textbook that I bought. Or that there are so many complicated "consequences" of this Axiom (of Choice), like Zorn's Lemma, Hausdorff's Maximal Principle.

Do you have any good books on Set Theory? Because without sufficient exercises, I will (still) find it hard to grasp these concepts. Same goes for any books that teach The Completeness Axiom, because I don't think wikipedia paints a good picture for newbies to understand it, nor can I find any good YouTube videos for it, and most of the other explanations that I can find appears very handwavy.

Log in to reply

The classic text is P.R. Halmos' "Naïve Set Theory", but it is pretty tough-going.

Log in to reply

Oh I bookmarked this and I forgot to reply.

Are you referring to this one? Okay! ordered!

Pretty tough-going? Even for you? Well, I guess I can only master this topic in the next decade.

Thanks for the dialog!

Log in to reply

That's the one. It should get you started.

Log in to reply

Thank you! You're really really helpful!!

I am aware of more elegant proofs for this than the one that follows.

However, I find this version to be easier to grasp for people struggling with the concept.

1) 31=0.333...=0.3

2) 3×31=3×0.333...=0.999...=0.9

However,

3) 3×31=33=1

From 2) we get: 4) 3×31=0.9

From 3) we get: 5) 3×31=1

If we combine 4) and 5) we get: 6) 1=3×31=0.9

And finally, 6) reduces down to: 7) 1=0.9

The more elegant proofs are... well... more elegant in the way that they convey the general pattern going on beneath the surface that can then be abstracted to other scenarios, such as the ever-popular 0.12. However, those can be hard for people to grasp.

I find that the 3×31 proof is easier for most people to grasp, in that it opens the door enough for them to realize that there's something really weird going on here.

Which is important. Because, and let's be honest about this, this 1=0.9 business is really freaking weird. Anything that helps crack the door open to let in the light is a good thing, in my book. :)

x=0.9⇒10x=9.9⇒10x−x=9.9−0.9⇒9x=9⇒x=1

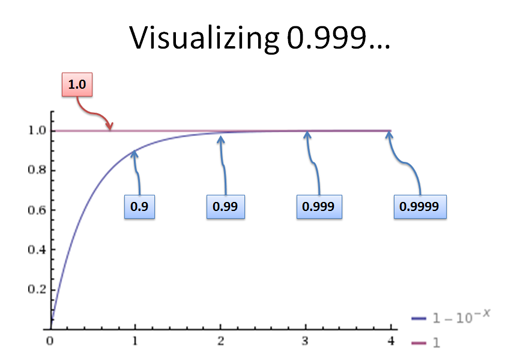

In one solution I wrote, there is an argument about whether 0.99999... equals to 1, and many of this community's respected member point out that it is, when I don't personally believe it is equal. The evaluation of limit in the infinite sum of n=1∑∞9(0.1)n

shows that it tends to reach 1, but never exact 1. I will keep an eye on respected members for this

Log in to reply

The trick here is that we are limited by our finite nature. We could never actually count up all of those fractions.

However, we can still represent the value of an infinite series numerically - providing that it converges. The value of an infinite series becomes that point of convergence.

I turns out that 0.9 is just such a converging series. The value of that series genuinely is 1.

This is why the limit of an infinite series is typically represented with the limit notation rather than with a sigma notation as you have used above. The limit notation more accurately conveys what's going on.

Annoyingly, I can't work out how to express a limit notation in the latex formatting for this site. If anyone else in the comments can help me out, I'd consider it a kindness. :)

Log in to reply

concepts like limits at infinity are just conventions... if we are to depend on conventions here is another one: 1-0.99999999999999999.............=epsilon epsilon is a number smaller than any thinkable number, such definition of infinity is that it is larger than any thinkable number...

It is 1 because the limit of the partial summs is 1. Another way to illustrate this is to think about which Infinitesimals exist in the reals(only 0), because the difference between 1 and the infinite sum obviously is an infinitesimal.

More proofs here than I have the patience to read

Yes it is. there are 3 ways:

1/3 = 0.3333333333333333... so multiplying by 3 on both sides we get 1= 0.9999999999999999999.... OR 0.9 can be thought as 1019+1029+1039.... (infinite GP.) OR x = 0.999999999... 10 x = 9.99999999999.... 9 x = 9.9999999999...-0.999999999999.... = 9 x = 1

There is a wiki about this topic here: is 0.999... = 1?

What you need to ask yourself regarding this topic is which set of numbers are you using? On the real line .9 repeating equals 1. The only way .9 < 1, as your answer to this question would have us believe, is if we were dealing in rational numbers only. The problem with asking this question of the rational numbers is that .9 repeating doesn't exist. Because of the analytical definition of the real line the limit of the sum that is .9 repeating exists and it is one.

Interesting how many proofs rely on the concept that 0.3recurring = 1/3. This is only true is 0.9recurring =1. In other words you are proving nothing. 0.3recurring is an approximation to 1/3.

Log in to reply

The notion of a mathematical limit is complex. Certainly 0.33333, 0.33333333333, or even 0.33333...3 (with one million 3s after the decimal point), are all approximations to 31. The mathematical idea of a limit allows for the possibility of having an infinite number of 3s after the decimal point, and then 0.3˙ is a number different from all the approximations with only a finite number of 3s, and is equal to 31.

The decimal number system is like that. All numbers have an infinite decimal expansion, and only very special numbers have decimal expansions which are finite, in that they can end in an infinite number of 0s (like 0.326=0.326000000…). Writing down only a finite number of terms after the decimal point gives an approximation to the number. As another example, 1.414 is an approximation to 2, but that does not take away the fact that 2 has an exact decimal expression which involves an infinite number of numbers after the decimal point.

Oddly enough, it is precisely the special numbers (which have a finite decimal expansion) which cause people problems, since they are also the numbers which can be written in two different ways, with or without recurring 9s. For example 0.326=0.32599999…=0.3259˙.

This isn't true, 0.3=31 and it is not an approximation.

Note that the ⋅ means that the 3's repeat forever. In other words, it represents n→∞lim3×k=1∑n10−k=31.

bing bang theory depents on thant 1 is infinetely larger the any lim-- 0.9999999999999....

Log in to reply

prove it man

Log in to reply

that ı exist... you too...