Lectures on Quantum Mechanics 4: Operators and the Dirac Notation

By now you should be aware that QM is very mathematical. As the mathematical complexity of physics increases, very complicated equations should be handled with very economic representations. Theoretical mathematicians in the past century have devoted great labour in the organization and abstraction of functions and algebraic structures. In doing so, physicists who were struggling with frightening equations were beginning to take advantage of what was new in math. Not surprisingly, the founders of QM did just that. To describe the physics of QM, much of the formalism is structured around functional analysis and linear operators. I will not go into too much detail on both, so I will explain why functional analysis and linear operators are so important in quantum theory.

Linear Operators in Hilbert Space

The space in which wavefunctions inhabit is determined by the four properties of wavefunctions outlined in Lecture 3. This is the Hilbert space. The Hilbert space is remarkable for many reasons, particularly in the generalization of the dot product (the inner product) in arbitrarily many dimensions (up to infinite dimensions). For technical reasons, the Hilbert space is also called the complete inner product space (here complete means linear). In QM, we need to know the following properties. I will represent everything in the Dirac notation (also known as the bra-ket notation), which is a quick and tidy way of expressing inner products.

1) The inner product for two vectors and then

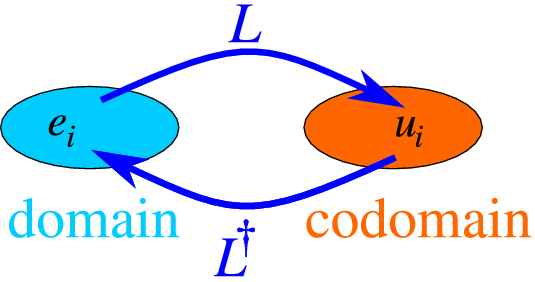

where is the adjoint (complex-conjugate transpose) of the vector .

adjoint

adjoint

Note: In mathematics, the adjoint of a matrix is often denoted , but physicists find it much cooler to use the dagger . I should add that where represents taking the complex conjugate of each entry and represents the transpose of a matrix. You can't transpose a function, so in the end of the day.

Similarly, the inner product for two functions over the interval is

2) A linear transformation for a matrix is given by the matrix product, where is a square matrix.

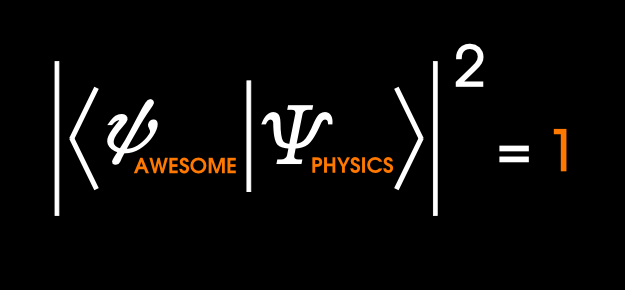

3) A function is normalized if . Two functions are orthogonal if . A set of functions is orthonormal if where is the Kronecker delta.

4) A set of functions is complete if any other function can be expressed as a linear combination of the set of functions

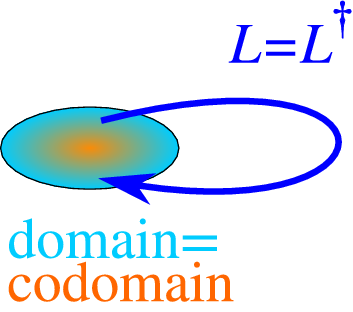

Hermitian Operators

In QM position, momentum, and energy are now called observables, and each observables are represented by a special type of linear operator: the Hermitian operator. What makes Hermitian operators special is that the adjoint of a matrix or function is equal to itself. This is why Hermitian operators are sometimes called self-adjoint operators.

self-adjoint

self-adjoint

Hermitian operators play a major role in QM because it conveniently describes the expectation values of observables (the expectation values of Hermitian operators are always real).

But how do we know if an operator is Hermitian? Consider the integral definition of expectation of an operator :

In Dirac notation, we denote the above integral . To test if the operator is Hermitian, we must show that

The Commutator

The commutator used in QM follows from ring theory, which is denoted by square brackets. This bracket notation works differently from Dirac's bra-ket notation. In abstract terms, the commutator is a measure of how two operations fail at commuting. If two operators commute, then . Thus the commutator is calculated as For example, the multiplication of numbers is commutative; hence, . But what about the position and momentum operators? Recall from Lecture 2 that

and Since these operators act on functions, let's introduce a test wavefunction .

Therefore

Although the commutator was designed to test commutative algebras, physics exploits the commutator in a clever way. Derivatives are important in physics, and in QM we take the time derivative of the expectation value of observables. Let's see where the math takes us.

By the product rule

Since the Schrödinger equation is we can simplify the above equation:

Now is Hermitian, so ; therefore,

This is an important result that has wide applications in QM, we will hopefully encounter it in the future.

Visit my set Lectures on Quantum Mechanics for more notes.

Problems

Use the commutator to prove the Ehrenfest theorem Hint: Remember and the commutator follow these identities.

Use the commutator to prove the Virial theorem

Consider the function Prove that is a necessary condition for to be normalized. Note that means . If are real, then it is equivalent to the square of its absolute value.

Use the Dirac notation (bra-ket notation) to prove that the necessary condition in Problem 3 is true for all orthonormal functions .

Use the Dirac notation (bra-ket notation) to prove where are the energy eigenvalues. Give a physical interpretation of this fact.

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

Quite heavy mathematics! I just know enough calculus but those Greek letters were driving me out!

If we use the Schrodinger wave equation as the starting point for the development of quantum mechanics, then Fourier analysis would be the natural vehicle for examining the solutions of the wave equation. It should be pointed out that a Hilbert space can be represented by Fourier series, i.,e., a "vector" in Hilbert space is an infinite continuous sum of waves. Moreover, all of these infinite continuous sums of waves form an orthonormal basis, which is what makes for a linear vector space. I think the Hilbert space formalism of quantum mechanics is more easily understood once its Fourier series foundations are realized.

Log in to reply

True. I think I will talk about the x,p being conjugate variables in Fourier. Fourier integrals were used in Lecture 2 when I discussed about the wave-packet of a wavefunction.

Actually, I am trying to be very general here. As long as the functions are orthonormal then it should work out.