Polynomial Interpolation example

I'm having trouble understanding this result (actually, this whole chapter of the Linear Algebra course really):

(a) Where did these fractions come from? The previous sections do not indicate how we got a rational function.

(b) Is the answer given, correct? When I multiplied these rational functions by the constants in question I got:

EDIT: For part (b) I figured out where I went wrong, just an algebraic error. is correctly given, I just misread the answer.

I feel like I have no idea what is going on here even though I just finished a class in linear algebra.

No vote yet

1 vote

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

@Mahdi Raza

I believed you're referring to this problem.

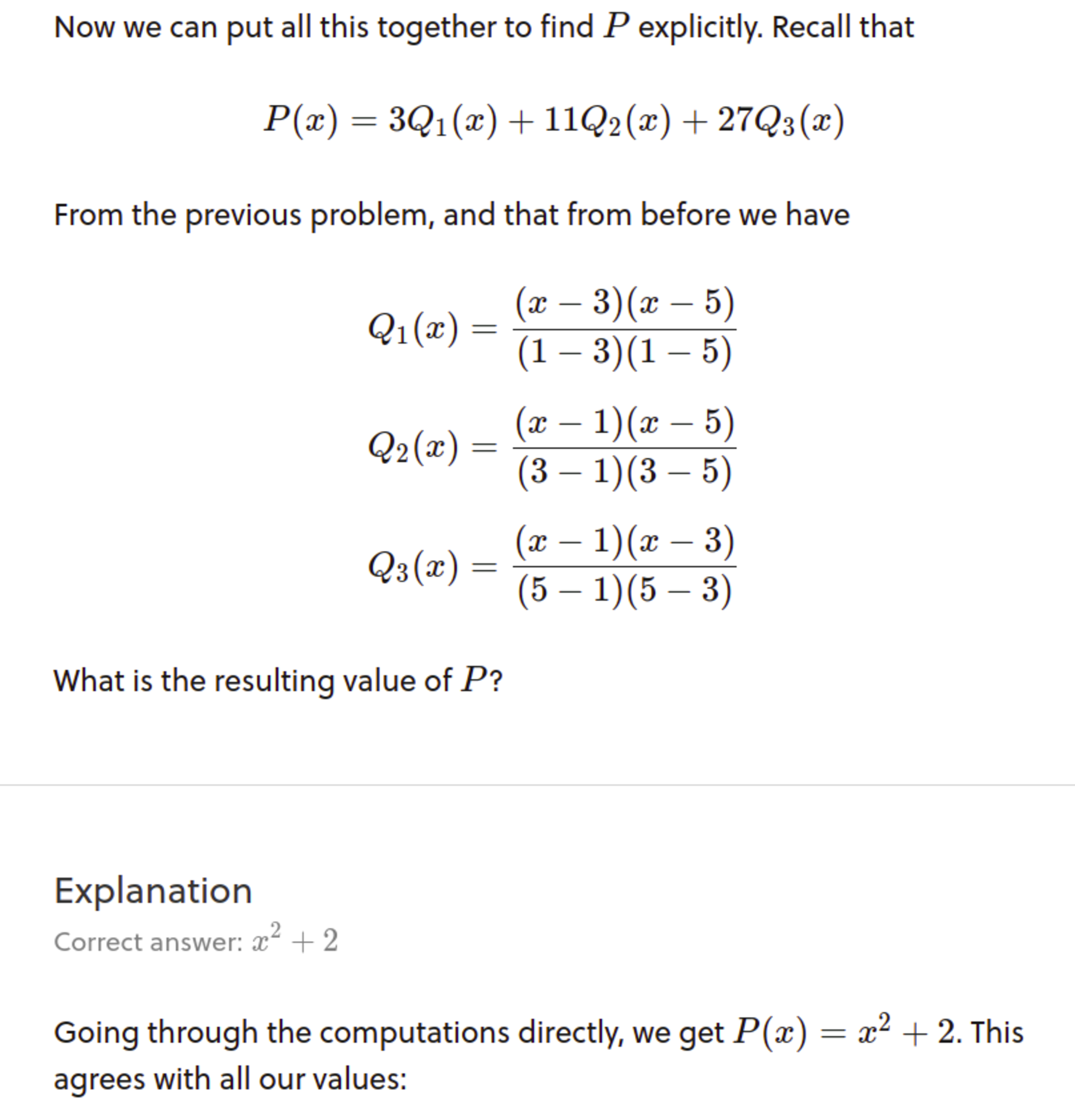

The previous problem demonstrates how you can get the coefficients 3,11,27.

If you substitute the three polynomials Q1(x),Q2(x),Q3(x) as stated into P(x), you get the desired x2+2.

Log in to reply

I know where the coefficients come from, but why are we dividing the polynomials by (1−3)(1−5), etc.? This process isn't explained at all.

I figured out where my math went wrong, I did get x2+2 after all.

Log in to reply

Let's say we want to interpolate a set of data points (a1,b1),(a2,b2),…,(an,bn) with a polynomial. There are a few real-world applications where this is desirable, so this isn't just an academic exercise. But let's not get into all that now.

If we express the interpolating polynomial p(x) as p0+p1x+p2x2+⋯+pn−1xn−1, then we'd have to solve the system of n equations p(ai)=bi for the coefficients of p(x), which is messy and unpleasant.

A better way is to express p(x) as a linear combination of polynomials Qj(x) that are carefully constructed so as to make the interpolation process as smooth as possible.

Imagine it were possible to define a polynomial Qj(x) that satisfies Qj(ai)=0 if i=j but Qj(aj)=1. In other words, Qj vanishes at all of the a's except for aj where it's 1.

Assuming for the moment that it's possible to do this, then consider the polynomial p(x)=b1Q1(x)+b2Q2(x)+⋯+bnQn(x). If we plug in aj, then we get p(aj)=b1Q1(aj)+b2Q2(aj)+⋯+bnQn(aj)=b1×0+⋯+bj×1+⋯+bn×0=bj. So the linear combination of these hypothetical Q's with weights given by the bj's, the y-coordinates of the data points, is precisely the interpolating polynomial we're after.

We just have to show that the Q's exist. We can do this by constructing them. The polynomial (x−a1)(x−a2)…(x−aj−1)(x−aj+1)…(x−an) is designed to be 0 at every a except for aj. This is almost what we need, but the polynomial isn't 1 at aj.

The simple fix is to take the polynomial above and then divide by (aj−a1)(aj−a2)…(aj−aj−1)(aj−aj+1)…(aj−an). This gives us a formula for Qj(x):

Qj(x)=(aj−a1)(aj−a2)…(aj−aj−1)(aj−aj+1)…(aj−an)(x−a1)(x−a2)…(x−aj−1)(x−aj+1)…(x−an).

Hopefully, that explains why we divide by (1−3)(1−5) in the problem you reference above.

In the future, if you have concerns about a problem's wording/clarity/etc., you can report the problem. See how here.