Problems with diagonals

Alright, so I've been bombarded /bombarded myself with questions lately and I either a) can't solve them or b) don't have the time. So if you can answer any of the following questions or even yeild a clue as what to do I'd really appreciate it

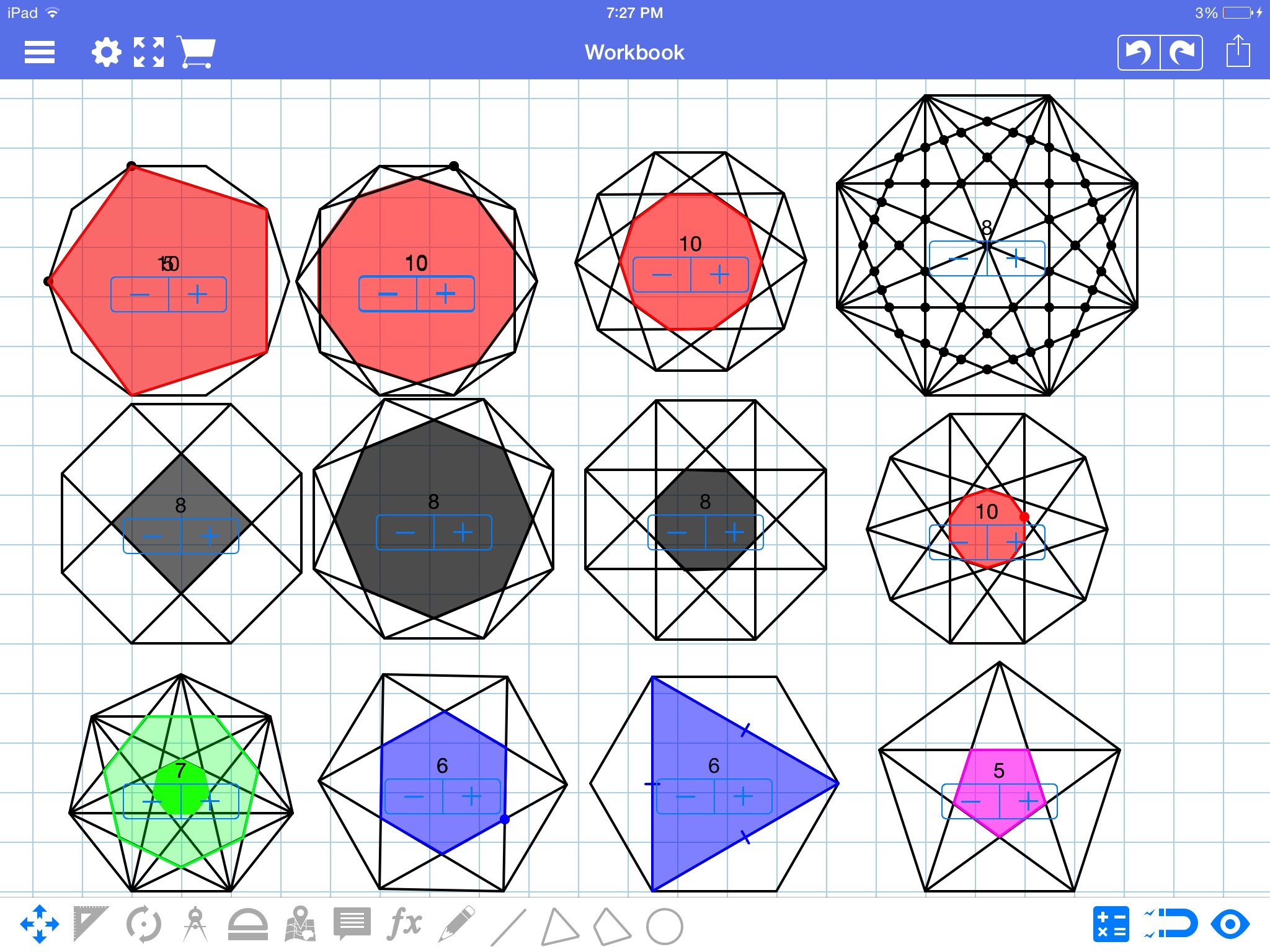

a) what's the probability that when two random diagonals of a polygon are chosen, they intersect within the region of the polygon. A general formula for all polygons that don't have an intersection made of more than two diagonals is

b) what's the area of the n-gon formed in a 2n-sided figure by connecting 1/2 of everyother vertex. (Exg: connecting 1/2 of everyother vertex of an octagon will form a square.)

C) what's the area of the 2n sided figure formed by connecting everyother vertex in a 2n-gon. (Exg: when doing this, an octagon is formed inside an octagon)

D) what's the area created by joining every k th vertex. I personally think that the best approach to this is to find the length of the diagonal when k divides n without remainder. This is much easier and, in my opinion, actually possible.

Most of the info that I along with some others have generated is in the comment section of this problem.

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

Note that under affine transformations, interior polygons are still similar to exterior polygons and so the answer to (b), (c) and (d) hold for non-regular polygons.

Log in to reply

Nice observation! But for now I'm just trying to prove the cases for regular polygons. Irregular polygons is the next step

Log in to reply

Yeah, it should be easy enough to prove after generalising joining every kth point for regular polygons.

Log in to reply

So far, for even n, and joining every other vertex, I'm getting 2na2(1−cos(180−n360))(cotn360)

Where n is the number of sides of the reference polygon and x is the sidelength of the reference polygon.

EDIT:

If k divides n without remainder, the formula is 8kia2n(cotnki180)(csc2(n180))(1−cos(nki360)) where k is joining every kth vertex

What is the maximum possible points of intersection of 2 circles???

For a) you can note that each intersection of diagonals inside the polygon is in fact determined by the two pairs of points that determine those diagonals; also, if you choose four points at random, whatever the set of four points it is, you can join two pair of them appropiately to construct an intersection, so the bijection tells you that the number of intersections is nC4. The number of pairs of diagonals is got to be dC2 where d is the number of diagonals which can easily be reduced to n(n-3)/2. The probability is then the quotient.

(For the case of regular polygons)

Using complex numbers (esp roots of unity) can be very helpful. It is clear that we will get a regular polygon (by symmetry), and hence mainly need to find the radius / side length.