Squares on a grid

In a set of lattice points, define a "grid square" to be a square whose vertices are lattice points and sides are along the axis. Define a "tilted square" to be a square whose vertices are lattice points and sides are not along the axis.

Prove that in a grid, the number of grid squares and tilted squares, is equal to the number of tilted squares in a grid.

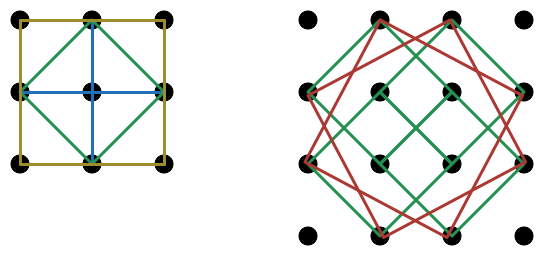

For example, in the above image, the grid has 5 grid squares and 1 tilted square, and the grid has 6 tilted squares.

For the solution, scroll and see the last rooted comment. It's been downvoted so that there is spoiler space for you to think about this problem.

No vote yet

1 vote

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

We can do this by brute force. For a n×n grid, the number of grid squares is simply the sum of squares, as there is 1 largest square, 4 next largest square, etc, so we have

k=1∑nk2=61n(n+1)(2n+1)={1,5,14,30,55,91,...)

Figuring out the number of tilted squares is harder, but we can discern a pattern by inspection, looking at the number of different sized tilted squares (touching sides of largest square grids to the smallest) by way of a kind of an induction

0=01=1(1)6=1(2)+4(1)20=1(3)+4(2)+9(1)50=1(4)+4(3)+9(2)+16(1)105=1(5)+4(4)+9(3)+16(2)+25(1)

So that we have

k=1∑nk2(n−k)=121(n−1)n2(n+1)={0,1,6,20,50,105,...)

From these two, we can show that

61n(n+1)(2n+1)+121(n−1)n2(n+1)=121n(n+1)2(n+2)

And thus the conjecture is proven. I’m sure there might be an more elegant way of showing this, which would mean a quicker way of working out the total number of squares, grid and tilted, in a square lattice, but I’d have to think about it.

Log in to reply

Thanks for proving the total count pair up!

Yes, there is an extremely elegant bijection.

Log in to reply

Man.... still scratching my head with that one, there's actually a bijection?

No, don't spill the bijection just yet! Gimme more time, it's one of those fun problems to think about.

I can see sort of a bijection based on the pattern that I've described, but the geometrical transformation rule eludes me. Hmm.

Okay, it has to do with the centers of the squares. Some kind of a bijection between the centers of the squares from one grid to the next largest. I don't know quite the best way to express it. But the key is that the center of any square, grid or tilted, always fall in integral coordinate multiples of 21, in any grid, so we set up a bijection accordingly. For example, the two largest squares in the 2x2 grid share the same center as the two largest squares in the 3x3 grid, and likewise for the next 4 squares of each.

Sir, can you disclose the bijection ?

How do we generalize this for a n*m grid?

I found a bijection, but I can't explain the rule. But basically, for all the squares on the n×n grid, you move one corner NE 21 units, one corner NW21 units, one corner SW 21 units, and one corner SE 21 units.

Log in to reply

Hm ... What does the large n×n square gets mapped to? It seems like you will end up with embedding it in a (n+2)×(n+2) grid?

You have to be careful with how/where you're moving, so that you don't step out of the box.

Log in to reply

Well, I'm moving the vertices 21 to the side, so actually the vertices of the squares are mapped from the centers of the unit squares of the grid to the corners of the grid. For example, if there was a 3×3 grid, it maps it to the corners of the unit squares of the 3×3 grid, which is a 4×4 grid (if that made any sense)

Log in to reply

Maybe. Work on simplifying the relationship, so that it becomes (almost immediately) clear why we do indeed have a bijection.

It is possible to explain how/why the large yellow square and the green square, both end up mapping to the red squares.

Log in to reply

Another idea is to use induction. Assume that all squares that can be fit inside a smaller grid map to the (n+1)2 grid, and we just need to prove that all squares that can't fit in a smaller grid in the n2 grid map to all the squares that can't fit in a smaller grid in the (n+1)2 grid one.

But they do map, because if you sort of rotate the outermost points of the n2 grid in a clockwise direction a little, and then add in 4 corner points, it becomes the (n+1)2 grid.

Log in to reply

That induction bijection step that you described, is most likely just the bijection step directly. IE if the bijections are all equal throughout the induction steps, you can just apply them all at once.

Log in to reply

The trouble with that is that the points move differently based on which square I am mapping (although all the points end up as points on the grid) so I was worried that it might not be legitimate.

Is there yet a better solution?

Log in to reply

Scroll down and see my solution :)

I too am interested in induction for this problem....

Fine problem https://oeis.org/A002415

On the left side are a series of squares of increasing sides, with inscribed tilted squares. It is readily seen that the number of inscribed tilted squares in a n−1×n−1 square plus 1 equals to the number of inscribed tilted squares in a n×n square.

On the right side note that for any n×n square there is 1 largest grid square, 4 next largest grid square, 9 next largest, etc. This corresponds to the number of grid squares in the n−1×n−1 square, i.e. 1 largest grid square, 4 next largest square, etc. Hence, there's a bijection of the number of grid squares, but for the number of the smallest grid square in the n×n square. But since we are counting only tilted squares in the n×n square, the count of the smallest grid square does not matter.

Every grid square of any size has associated with it tilted squares that are inscribed in it, and every tilted square of any size has associated with it a grid square that circumscribes it. So, counting all the tilted squares in a n×n square is the same as counting all the squares, grid and titled, in a n−1×n−1 square. This is the bijection.

Spoiler space. If you do not want to see the bijection, then don't read the sub-comments.

Log in to reply

Set up the n×n square grid in the TOP LEFT of the (n+1)×(n+1) square grid. Notice that we have an additional row to the bottom, and column to the right.

Given any square in the n×n grid, we define the TR = TOP (RIGHT) corner to the the topmost corner. If there are 2 such corners (then we have a grid square), and we will take the right most one.

Creating the bijection:

Fix the TR corner.

The corner that is clockwise from it is the RB = RIGHT (Bottom) corner. We will move this corner to the right by 1.

The corner that is clockwise from it is the BL = BOTTOM (left) corner. We will move this corner to the right by 1 and bottom by 1.

The corer that is clockwise form it is the LT = LEFT (top) corner. We will move this corner to the bottom by 1.

Claim: This gives us a square in the n+1 grid.

Proof: It is clear that the defined points lie in the grid due to the extra row and column that we have. It remains to show that the side lengths are equal. This is obvious by definition, since if the original square length is a2+b2, then the new length is (a+1)2+b2.

Claim: This does not give us a grid square in the n+1 grid.

Proof: Suppose it does. Then show that the TR corner would not be the top most. This is because the LT corner gets moved down 1 to become parallel to TR.

Claim: This is a surjection.

Following the TR-RB corners, it is clear that each n square gives a unique n+1 square.

Claim: This is an injection.

It remains to show how we can go back. The mapping is obvious, starting again with the TOP corner (which is unique since there are no grid square), which will be our TR corner.

Hence, we have a bijection, and we are done.

Here is the bijection for the n=3 case that was depicted above. Notice that the TR corner of each square is fixed, and then they are rotated counter-clockwise.

Log in to reply

I was looking for the actual formula or transform that will "plot" the points of each square from one grid to the next, but so far all of my efforts are anything but elegant. But, given any square of side length m in the smaller grid, there corresponds to that a square of side length m+1 in the larger grid, and if you consider just the squares that are "inscribed" in such squares, it's easy to see that the one grid square and m−1 tilted squares inscribed in the square of side length m sums up to the m tilted squares inscribed in the square of side length m+1. That's the basic idea. How to implement that with an actual transform formula, I haven't been able to work out in an elegant way, without using lots of things like Floor functions.

Log in to reply

There is no bijection that will map the n2 points onto the (n+1)2−4 points, in part since the number of points are different.

I'm not too sure what you mean by "given any square of side length m, ...". Is there the possibility that you mean the mapping is from m2 to m2+1? If so, that will only work for small cases of n, where we do not have too many different lengths. For example, the square with side length 10 cannot map to a square of side length 11.

Log in to reply

Wow, all I couldn't do was find a simple way to describe the bijection.

Downvoted your post and upvoted your solution :)

Okay, maybe I still have the opportunity to explain in better detail my approach to this problem, once I collect enough of my time to do it. As I said from the beginning my approach is related to the pattern that I've posted originally, but for now I'll forget about any kind of a "transform" and just focus on showing a bijection "in English". Then we can compare our approaches. By the way, what program are you using to produce the graphics? It might help me to more easily illustrate my approach.

Once again, I got sidetracked on the whole idea of how to even define or describe a "transform" for something like this. But I know that's not what this problem calls for.

Log in to reply

Your observation about the mapping of centers by (21,21) also holds in my bijection (if you follow how the vertices adjust).

In fact, with the problem, the issue is to define / describe the bijection, and finding a clear explanation for how to establish the mapping. To me, it is still slightly surprising that the number of squares are equal and that such a mapping exists.

I use a program called OmniGraffle, which is great for such designs. However, it doesn't deal well with mathematical constructions.

Log in to reply

Aw, I'm still old fashioned. I'm neither using 1) Apple nor 2) a smartphone. Nix OmniGraffle. I'll think of something else.

Why is that when I'm using ever larger computer monitors in which to do my work, the rest of the world is going to smaller and smaller monitors, down to the size of a watch? I don't get it. If I ever get convicted and sent to prison, one way I could be tortured is to be forced to do math on Apple watch. Oh, the inhumanity.

Log in to reply

Geogebra is a good mathematical drawing program.

I love screen real estate. I already use a 20 inch display at work (in addition to my laptop), and am considering adding an additional screen.

Possible small typo : """The corner that is clockwise from it is the BL = BOTTOM (left) corner. We will move this corner to the right by 1 and bottom by 2. """ Should this 2 be a 1?

This is great and generalises well to triangle analogue of this question in an obvious way. I'm going to see if this kind of relation generalises to the 3D case of counting cubes. Thanks!

Log in to reply

Thanks, edited!

I would love to see the triangle analogue and the 3-D case :)

Log in to reply

A quick update : Triangles and hexagons have very similar patterns.

I wrote a quick programme to get some data on 3D and 4D cubes to help see if a simple pattern like this exists. It doesn't look like a simple pattern exists (at least I couldn't see one immediately) but maybe something more complicated with quarternions and similar things may exist - interesting stuff. Some seemingly useful (but too complicated for me right now ) paper solving this higher dimensional problem.