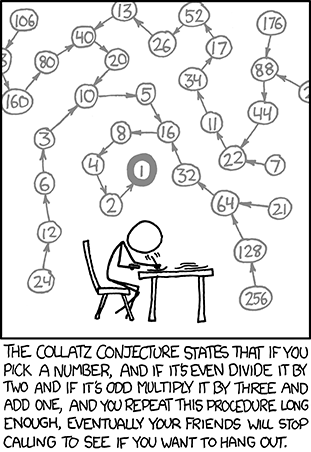

The most difficult - yet so easy to understand - problem in the world!

Take any natural number . If is even, divide it by to get . If is odd, multiply it by and add to obtain . Repeat the process indefinitely. The problem is to prove that no matter what number you start with, you will always eventually reach .

Don't be fooled by the simplicity of this problem, great mathematicians like Erdős had great trouble proving it. The latter even said: "Mathematics may not be ready for such problems."

No vote yet

1 vote

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

When do you predict that the Collatz conjecture will be solved? @Sharky Kesa @Daniel Liu @Daniel Chiu @Trevor B.

Log in to reply

Possibly in the next decade given the number of young mathematicians rising up and are being seen on Brilliant.

The Collatz Conjecture? or The Ulam's Conjecture?

Log in to reply

It's commonly named after Collatz name but it is also named Ulam's conjecture because he used to talk about it in the lectures he gave.

Log in to reply

I did not understand what were you saying about odd numbers. Even one is true but can you explain me the odd process ?

Log in to reply

Start with any natural number. If the number is even, divide it by two. If it is odd, triple it and add one. Repeat the process with the new number so formed. Ultimately the number 1 is reached.

Log in to reply

Even one is true. But what about odd ? Let the no. be 5. if we triple it and add one, we will get 16 and then 49 then 148 ......... Which I don't think would approach 1. Or am I not getting the process. Can u explain the process with examples.

Log in to reply

When you got 16, you'll have to use the operation we restricted to even numbers, that is: n/2. And so you will get 8. Repeat it again you'll have 4, then 2, then 1!

Log in to reply

OK. Now I got it very well. Thanks

Log in to reply

You're welcome!

You have done the operation wrong. Lets call the operation C(x) where x is your starting number.

C(5)=16,C(16)=8,C(8)=4,C(4)=2,C(2)=1. And thus the operation ends.

I also thought this ....one day....Thanks for posting it

couldn't we just consider it true until proven wrong? =)

Log in to reply

That wouldn't be helpful in any way.

Log in to reply

Yep, just taking the lazy way out.

Wouldn't it be correct if I say it will also reach every time reach 2 .

Log in to reply

No. If you start on 2 itself, then you will have to carry out the operation n/2 anyway. You have to COMPLETE the sequence and hence end with 1.

Log in to reply

But by starting with 2 , 2 comes in our sequence. How will you write the sequence - only 1 or 2 , 1. Consider the following example - We take n = 5 .Then how would you write the sequence like this - 5 , 16 , 8 , 4 , 2 , 1 or simply ignoring 5, by - 16, 8 , 4 , 2 , 1. Of course first one 's correct so we could never ever find a sequence except n = 1 in which two does not come.

Le problème de Syracuse ;)