The Shortest Path Between Two Points is a...

Line? Cool. Resolved. Move on.

My AP Government and Politics teacher (awesome dude) likes to reply to my scientific jargon with "The shortest path between two points is a straight line drawn in opposite directions!" I then say "Only in Eucledian Space!" Sometimes I add "In Minkowski Space-Time, a straight line connecting two points makes up the longest possible path."

SO. Any of you know any other spaces in which a straight line is actually the longest path between two points - or just simply not the shortest one?

No vote yet

1 vote

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

First of all, a "straight line" in any space is presumed to be a geodesic, which is, by mathematical definition, an extremium between two points. Notice I said "extremium", it doesn't necessarily mean the shortest distance, sometimes it can be the greatest distance [even if a straight line path is followed--per Calvin Lin's comments]. I can fly on a great circle route from Los Angeles to New York over America, or I can choose to go the other way and get there just the same. The same thing can happen on pseudospheres as well as regular spheres. When extended indefinitely, geodesics can often eventually intersect themselves, and so you'd have a "short way", and "the long way", even though both paths are on the same extremium "straight line".

See graphic for examples of geodesics on a pseudosphere.

For those interested in differential geometry, geodesics on a surface have the property that at all points of the geodesic curve, the curvature vector of the geodesic curve is the same as the normal vector of the surface at that point, differing only in magnitude. In other words, a plane defined by the tangent of the curve and the normal of the surface at any point contains the circle defining the radius of curvature of the geodesic at that point.

Log in to reply

I disagree with your definition of geodesic as "extremium". I think think of many other routes from Los Angeles to New York, that are longer than the great circle going the other way. E.g. going to the Bermuda triangle.

The definition of a geodesic, is that it is locally the shortest distance between 2 points.

It also need not be true that "geodesics eventually intersect themselves", even on closed, compact, connected, manifolds. For example, take the torus [0,1]×[0,1], then any geodesic is of the form y≡kx(mod1), and clearly it doesn't intersect itself for irrational k. Since there are uncountably many irrationals vs countably many rationals, it is unlikely for a geodesic to intersect itself.

The torus is also a good example of "infinitely many geodesics between (any) 2 points", which can appear contradictory at the start (so why isn't it contradictory?)

Log in to reply

Technically, a geodesic on a surface is determined by the conditions that I posted--at least in differential geometry. In Euclidean geometry, it's defined to be the shortest distance between two points The term "longest distance between two points" on any surface really doesn't have much meaning because one can always meander and violate the local conditions for a geodesic. The point of having this conversation is that when earlier ideas about "shortest distances" are combined with the mathematical apparatus of differential geometry (now a staple in physics), the notion of "shortest distance" only has meaning locally, as you have pointed out. But it does not mean that if one travels on a geodesic (a "straight line" in any space, curved or otherwise), it's necessarily the shortest distance between two points.

The one place where the wording in my previous post can be tightened up is this sentence, "Notice I said "extremium", it doesn't necessarily mean the shortest distance, sometimes it can be the greatest distance." The weasel word "sometimes" apparently isn't enough to save it from criticism, and so more words have to be added to it, such as, "Notice I said "extremium", it doesn't necessarily mean the shortest distance, sometimes it can be the greatest distance even if a straight line path is followed". This can be true in some cases, as with perfect spheres, where a straight line is a great circle.

We agree on one point, which bears repeating. While "shortest distance between two points" has meaning both in Euclidean geometry and local differential geometry of curved spaces, it doesn't have useful mathematical meaning to speak of "greatest distance between two points" without qualification.

I'd like to point out that the mathematics of extremium, as in variational calc ulus, plays a significant role in the mathematical apparatuses of physics. In many instances, a thing or a system seems to behave as if it wants to minimize something, such as "taking the shortest path", which is often used to describe which path a ray of light takes. But light does not specifically seek the shortest path, it often ends up taking a roundabout way. Why? Because it is merely following the local conditions which defines a geodesic, which just so happens to be the shortest path in many--but not all--cases. Which is the point I think John Muradeli is trying to make. Physics is often guided by paradigms such as, "shortest path from A to B", or "least action", or "shortest spacetime interval", etc., but it's important to keep in mind that they are just paradigms, and do not actually indicate "motivation" of any particular system, i.e., a system isn't necessarily trying to do any of those, it is merely following a certain set of local conditions, similar to those defining a geodesic in differential geometry.

Alright I knew that (1) You were probably going to post (2) Things were going to get complicated.

So... Really, a list of fabric management systems (4D spacetime is one) with defined shortest paths would be great. But, now I have questions. So, geodesic. First time hearing this word. This stuff:

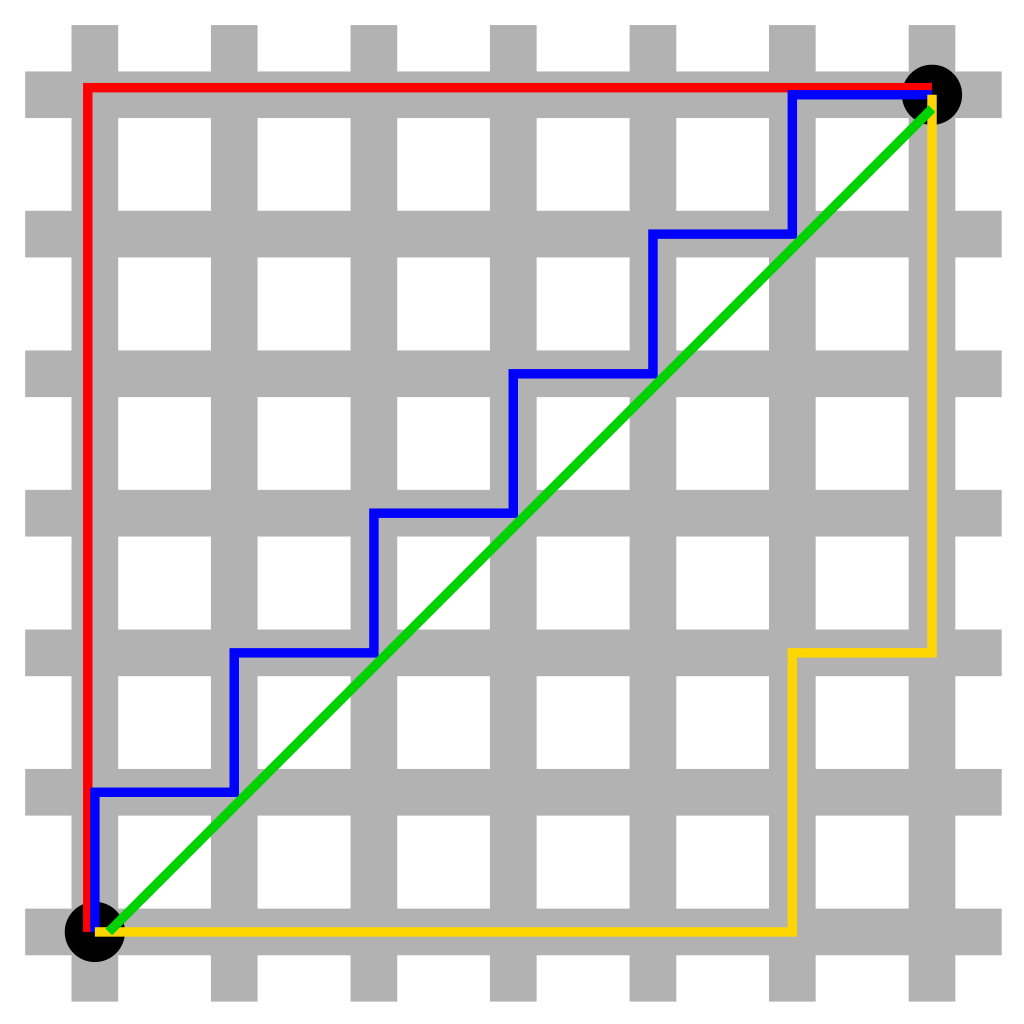

So, why are we complicating things? Why take a geodesic when you can... do this

Is it because we define those restrictions? I'm not as advanced in non-traditional geometry, but I can give an example - say, if you're passing by a black hole, it may be a good idea to take a curved path from A to B - if between A and B we can draw a line that passes through the event horizon. I'd reason this to be like finding the shortest path between two points located on opposite faces of a rectangular prism - assuming you must travel on the surface. The shortest path won't be a direct straight line over the prism, because when we unfold the shape into its 2D form, we see that when we draw a straight line and fold it back together we see a curved straight line (erm... bent). So is this it? Is this why when working with space under the influence of gravity, you use differential geometry and define new spaces? Lol I'm probably totally off xD

One more ex. So when we have undisturbed space, straight line path is the shortest path (RIGHT?). Now it may APPEAR as if we're taking a shortest path by traveling directly to point B (or, in pic, D), but this may not be so:

We rather take a curve around the spatial disturbance, and thus travel lesser overall distance. Is this it? Am I hitting it?

Log in to reply

I call this an example of "Euclidean chauvinism", i.e., a preference or a belief that "flat" Euclidean geometry is somehow especially endowed, a standard by which all other spaces are compared with. It's a risky assumption to make when doing theoretical physics, not very far different from Newton's idea of an absolute frame of reference. At best, it gets in the way of deeper understanding of physics. For example, a great many people believe that the Big Bang is an explosion of some kind that expands "into something". No, it doesn't expand into some kind of Euclidean space, it's spacetime itself that undergoes drastic internal changes. As another example, we often hear that it's possible to break a signal down into its "frequency components", like how an audio recording is decomposed with a frequency analyzer, so that it's a sum of a spectrum of sinusoidal waves, with variable amplitudes. Again, it's not true that such signals can only be decomposed into pure trigonometric waves. We can use just about any other set of orthogonal periodic functions that are decidedly not trigonometric to decompose and analyze a signal. In other words, sinusoidal functions are just another set of orthogonal periodic functions, Newton's absolute frame of reference is just another reference frame in relativity theory, and Euclidean space is just another space.

If you are on a surface trying to go from point A to point B, the "real off-the-surface shortest straight line distance from A to B" may have no meaning at all, because there can be a multiplicity of other curved spaces in which that surface is defined, so that the "real off-the-surface shortest straight distance from A to B" can depend on that other curved space, and so can have any range of values, including zero.

It should be noted that wormholes are not examples of "going from point A to point B off-the-surface". Wormhole travel is still very much on the surface.

Again, a technical point should be made here that "flat" Euclidean spaces do have some local properties that are unique among spaces. However, in physics, it's a chicken or the egg problem--is flat Euclidean space a fundamental, or is it emergent, i.e., dependent on a host of conditions that must be present before it can even exist? Topology addresses this question. Conservation laws in physics also critically depend on such things, so that, for instance, we cannot necessarily assume that energy is always conserved. Conditions have to first exist before we can have a law of conservation of energy.

Additional Note--When I was a teenager in the early 1960s, I bought a pocketbook in a local liquor store (that's right, a liquor store, where they sell booze!) of an hoary old 19th century text on non-Euclidean geometry. I think I still have it. It was the reason why I got interested in differential geometry. Today, in America, you can't find any math books at all any more in any "local stores". Indeed, even public libraries today carry far fewer math and physics books than they used to. Times have changed.

Log in to reply

Ermm... Eehh... Soooo.... is it like systems, then? I.e. - defined contingent upon purpose of analysis? Then... how about... we define... the "shortest path" to be... ummmmmmmmmmmm................... Lol no clue. I find it hard to find an absolute definition, because I constantly think of wormholes and know that you can go to the other side of the universe in an instant if conditions are right. Basically, I'm too stupid for this. But I'm smart enough to ask this:

"because there can be a multiplicity of other curved spaces in which that surface is defined, so that the "real shortest straight distance from A to B" can depend on that other curved space, and so can have any range of values, including zero."

But why bother, say, drawing a sphere in a vacuum, undisturbed, 3D space, around two points for which you're trying to find the shortest distance between, and analyzing the system from spherical perspective when you can just take the straight line? I mean, it seems to me that all you're doing is ascribing unnecessary definitions to physical properties, when more straightforward models exist. And, I think I came up with the best definition of shortest distance: "Assuming an object travels at a constant speed, for what path will the object reach point B from point A in shortest amount of time?" Now I expect you to say "Well, it depends, because quantum space stuff and your object can teleport to B without having to traverse the space in-between." Is that it? Do you define various spaces to account for possible external influences?

Log in to reply

John, I'm happy to see that you're interested in theoretical physics. Join the club! Lots of physicists are asking themselves the same things. And--you are right--quantum physics threatens to make a total mess out of the whole idea of even having surfaces and spaces at all. If you find yourself scratching your head over this, you're in excellent company.

I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics--Richard Feynman, who won the Nobel Prize for his work in Quantum Field Theory.

Addendum: In answer to your question about getting from A to B in the shortest amount of time", it's all about constraints, isn't it? For example, the shortest distance from A to B may be right across the lake, but I'll be taking the long way around if I have to walk. A lot of physics is like that.

Log in to reply

Lol... doubt it, besides later in the future or on free time. I'm really interested in the topic, but I have to put precedence on engineering and other practical stuff. Things like 2045 makes me go after the money - because I believe that in this age money has more power than it had ever before - and it will have much more in the next 30 years. Either way, an interesting question: At what point does a triangle on a sphere become non-Eucledian? I mean:

So if we drew the triangle on the ground, each leg say 3ft, it would be a regular triangle. But you're telling me that if we make those legs really long, the angles will be all messed up? So are angles dependent upon leg length relative to the circumference of the sphere, or...? Probably. Well, and I think I now understand somewhat how non-Eucledian geom can be useful. Like, we think we're going in a straight line on a mobius strip, but in reality, not really. Or on Earth. And thus, by creating a model that obeys the same restriction (i.e. I could get to China from USA by digging through Earth, but I probably will take ... a more civilized approach) as the system we're trying to analyze, we can make accurate predictions. Rite? I think so :D Now try and solve the new noobs weekly, if you dare ^.^

Log in to reply

There's a beautiful book called, "Gravitation", by Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler, that is the gold standard on textbooks about relativity. The cover of it is exactly about the same question. Check it out.

Technically speaking, as long as the triangle is on a non-Euclidean patch of surface, it is non-Euclidean, but in the limiting case, it can be treated as an Euclidean triangle. As an analogy, mechanics in physics is supposed to be relativistic, but as a good approximation in most ordinary cases classical Newtonian mechanics can be used to describe it. Physics is full of "okay, it's good enough to use" stuff. Niels Bohr even referred to this with his "correspondence principle:", but he was talking about quantum physics.

An interesting trivia is that Kip Thorne recently was a consultant in the making of "Interstellar", which has a lot of weird warped spacetime stuff.

Another trivia which may be a little mind-bending is that John Archibald Wheeler co-authored with Richard Feynman the infamous "Wheeler-Feynman Absorber Theory", which suggests that, among other things, events in the future can affect things in the present. Quantum-mechanically of course. Quantum physics is supposed to be weird, right?

Log in to reply

Hm, do you suggest I get this book? Do I have to know tensor calculus or something? I'm good upto Multivariable Calculus - and AP Physics C - which goes up to Maxwell's Equations, so a good deal of Vector Calc is involved.

And I knew this would be the case. It's just like with E=mc2 - the m is m0 divided by 1−v2/c2 - but we don't care for that because our v is never so great on common examples to significantly affect our E. So we're "approximately Eucledian,"

Log in to reply

Wow! I just checked. A new "Gravitation" book costs like about $200! Whoever knew that the copy I got a long time ago would prove to be such a good investment? Man. let me look around, there's gotta be a cheaper way to get a copy.

The book assumes that you have at least undergraduate level of math ability. But the book learning curve is still phenomenally steep.

Anyway, I have to go too.

Log in to reply

Lol damn I thought it would cost like 1$ or something - some good old books drop that low. By the way, ever read Penrose's "Road to Reality"? That book is my #1 book to read. But it will probably be the last cause MATHS QUANTUMS!!!

Log in to reply

Yeah, I have Penrose's "Road to Reality" buried somewhere in that pile of books in the garage. It's a favorite--so what's it doing in there? Really, I need to finish that bookcase.

Because it's M.C. Escher's birthday today, I'm gonna throw this in. More warped space stuff. Are you sure you know what a "shortest straight line distance" means in the geometries of Escher's feverish mind?

M C Escher

Log in to reply

You see? This is what I'm talking about. This stuff is insane! And imagine learning ALL THAT in a day. With 2045 avatars. But instead imagine trying to learn that manually and have $10,000 in your bank account. PRIORITIES! ("all that" I mean all math and all physics ever). But the link is totally awesome - thanks for that. And you should totally read that Penrose book - I heard he took like 8 years to write it! Alright I'ma let you go now. Thx ∀

The only such space is the space where the distance between any 2 points is 0.

Note that if we have 2 points x,y such that d(x,y)>0, then we can transverse indefinitely between these 2 points to lengthen our journey, and hence the "straight path between these 2 points" will never be the longest distance.

Furthermore, you can show that if we have 3 points with non-zero distance between each pair of points, then it will not satisfy " d(a,b)≥d(a,c)+d(c,b)" for all triplets of distinct points. This means that even if we add the restriction of "path cannot intersect itself", we are still doomed to trivial spaces.