A popular math problem is proving that 22/7 exceeds π, without resorting to known values of π or approximations by calculator. One method uses certain definite integrals which work out to 22/7 −π which is known to be greater than 0. But back around 250 BC, Archimedes was the first to prove that 22/7 exceeds π, by successive use of the trigonometric identity

Tan(2x)=1−(Tan(x))22Tan(x)

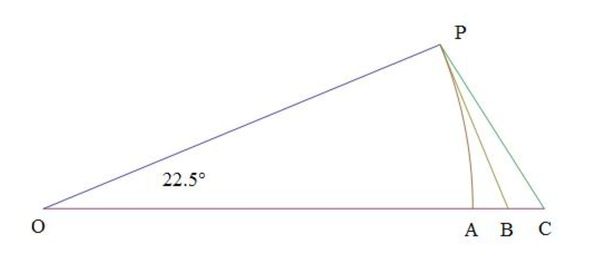

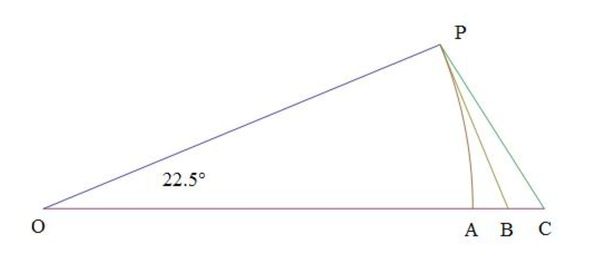

Starting with the regular hexagon, and doubling the number of sides until he reached a regular polygon of 96 sides, he was able to show that 22/7 does indeed exceed π. Unfortunately, he relied on a series of inequalities in his computations, the notes of which are lost, so we have no complete proof left to us from his works. So, here’s an updated version of his approach that will be an exact proof, beginning with the following diagram

where

∠OPB=90°

OP=OA=1

OB=Sec(n45°)

OC=(ba)(4n1)Csc(n45°)

In this diagram shown, n=2 and ba=725, a very crude apprximation of π. ba is selected so that OC>OB, so that it is clear that the areas are

[OPC]>[OPB]>[OPC]

That is

(8n1)(ba)>(21)Tan(n45°)>(8n1)π

so that if we can prove that for some sufficiently large n

(4n1)(ba)>Tan(n45°)

then we've proven that

ba>π

Now but there is a delightfully useful trigonometric identity to use for this purpose, which Archimedes didn't have

Tan(nx)=F(n,Tan(x))=i(1−iTan(x))n+(1+iTan(x))n(1−iTan(x))n−(1+iTan(x))n

If (4n1)(ba)>Tan(n45°), then

F(n,(4n1)(ba))>F(n,Tan(n45°)), (a little handwaving here), but since

F(n,Tan(n45°))=1, we have

F(n,(4n1)(ba))>1

So, for ba=722, all we have to do is to show that for some sufficiently large n, let's say n=24, which corresponds to the regular

96 sided polygon Archimedes used

F(n,(4n1)(ba))=F(24,(961)(722))>1

Using that trigonometric identity above, the exact final rational fraction is

30703991745883868538357400656084155837998635050071688218977613070617780371250623172531488874792422422762969087263790473600

Note that the first 6 digits of the numerator and denominator are

307061>307039

which conclusively and exactly proves that 22/7>π, without resorting to approximations, without using known computed values of π, nor infinite series, nor infinite products, nor infinite continued fractions.

Going further, we can let n=1557, corresponding to a regular polygon of 6228 sides, and let a/b=355/113, another famous and very accurate approximation. We end up with a rational fraction with a numerator and a denominator both 9105 digits long, the first 12 digits of each being

196554866601>196554866571

thus proving that 355/113>π as well.

Addendum: Note that as n→∞

Tan(x)=Tan(n(nx))=F(n,Tan(nx))≈F(n,(nx))

F(n,(nx))=i(1−nix)n+(1+nix)n(1−nix)n−(1+nix)n=ie−ix+eixe−ix−eix=Tan(x)

which shows the relationship between the exponential form of the Tan(x) function and the trigonometric identity given above for Tan(nx)

Easy Math Editor

This discussion board is a place to discuss our Daily Challenges and the math and science related to those challenges. Explanations are more than just a solution — they should explain the steps and thinking strategies that you used to obtain the solution. Comments should further the discussion of math and science.

When posting on Brilliant:

*italics*or_italics_**bold**or__bold__paragraph 1

paragraph 2

[example link](https://brilliant.org)> This is a quote# I indented these lines # 4 spaces, and now they show # up as a code block. print "hello world"\(...\)or\[...\]to ensure proper formatting.2 \times 32^{34}a_{i-1}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt{2}\sum_{i=1}^3\sin \theta\boxed{123}Comments

My favorite proof is this funny integral. 0<∫011+x2x4(1−x)4dx=722−π

Log in to reply

Well, it's true that it's hard to beat that one as "something that can be done on the back of an envelope". A large envelope anyway.

Wow.

Log in to reply

I know right!? :D

@Michael Mendrin , Your note inspired my next sum!

Integrate It! Part-V

https://brilliant.org/community-problem/integrate-it-part-v/?group=DvYD57CYrdYl&just_created=true

That's really something, u know!! Thankx for posting it.. Quite enlightening. :-)

Eh, but you know, at the point where I said, "a little handwaving here", there's actually more that needs to be said before this really becomes a complete proof. But this tiny detail will take up too much space to resolve.

Another proof that 722>π.

Log in to reply

Dude, you just published the solution of my problem! Why?!

Log in to reply

Probably because she didn't know you posted this as a problem?

Log in to reply

All right, but now she knows.

Log in to reply

Gimme a break!? How do I know that?? As Mr. Mendrin said, I did NOT know that. Why didn't you comment by inserting your problem + link direction instead of link only?? (¬‿¬)

Log in to reply

All right, since you now know, can you please delete your comment?

Log in to reply

Valentina, actually, I didn't mind you posting the solution to that classic definite integral. That was the one I was thinking about when I referred to them at the beginning of this short paper. But it's not the only one possible. Maybe you can post another that isn't the same as Avineil's posted problem?

Log in to reply

Right now, I have no idea. If something crosses to mind, I will post it here.

Also, can you tell me how to use + link that you are telling?

Log in to reply

Use

[your problem](link direction)Like you said Sir. I did not know that. Besides, I already knew this problem long time ago. This problem is a problem in Putnam competition.