求四邊形的面積

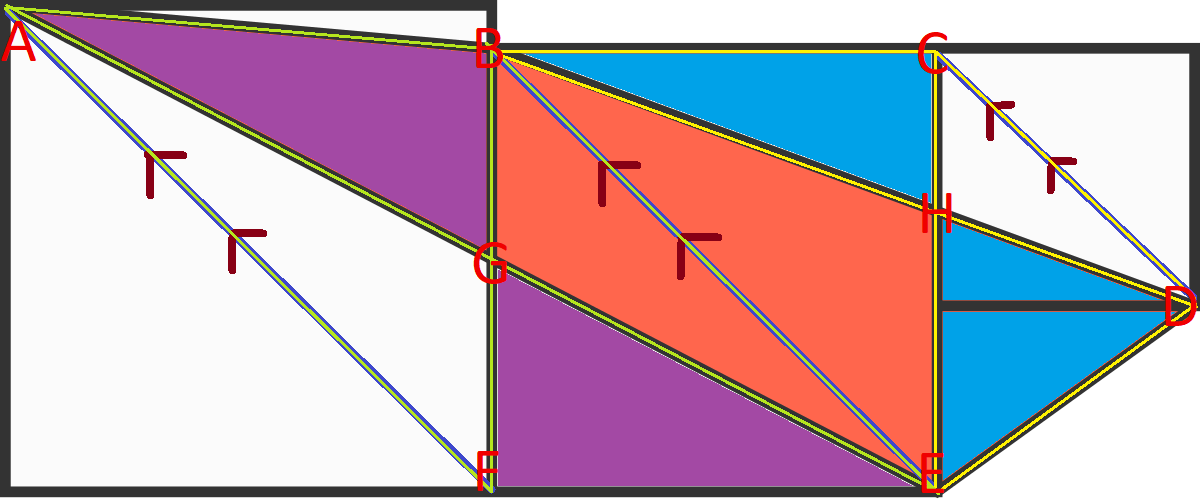

Three squares of different areas are side by side. The middle square’s area is 16, and its opposite sides are each collinear with an adjacent square’s side.

What is the area of the red quadrilateral?

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

36 solutions

Good explanation brother

The question seems random to me but once saw the solution it makes sense!

can someone please explain to me what seems to be intermediate steps that are not included to get from the top line to the middle and then to the 3rd. I can't reconcile the signs and multiplication to end up like it is presented here. Where did the denominator of 2 go? Thank you.

Log in to reply

is the formule to calcul an are of a triangle

Triangles are half rectangles and look close at the formula, it describes which parts are which triangle areas.

O started punching letters a, b as well, but thought it would not help me. So I have not had the idea of calculating bits and pieces like you did. Now I realized that in the end all literal calculations cancelled out. Nice solution

Why did you subtract the pink area? It wasn't part of the 3 squares.

Log in to reply

? Pink area is added after being calculated.

The pink area is supposed to be added, because it is part of the original red quadrilateral.

It's not subtracted, it's added

Beautiful presentation. Congratulations.

Why do you change the - sign between a-4 and 4-b? Maybe not why, but how?

Log in to reply

a > 4 but b < 4 .

- the side lengths of pink triangle are b and 4-b (with b<4)

- all other triangles are subtracted from the sum of all square areas, but the pink triangle is added.

wow, this is epic! very beautiful and clear!

Implied that the answer does not depend on a or b, let's set a=4 and b=0. (Technically, a=4+e and b=e where e is infinitesimally small.) The blue, green and pink areas vanish and the yellow and red areas become equal. So the answer is half of the area of a 4x8 rectangle.

Label the vertices and connect

A

C

,

G

E

,

F

I

.

Notice that

A

C

,

G

E

and

F

I

are parallel to each other. Then,

Δ

A

E

G

and

Δ

C

E

G

have the same areas (equal base, same height),

Δ

E

I

G

and

Δ

E

F

G

have the same areas (ditto), which concludes that the area of quadrilateral

A

E

I

G

is the area of the square

C

E

F

G

.

連AC、GE、FI,可知AC平行GE平行FI,所以三角形AEG面積=三角形CEG面積,三角形EIG面積=三角形EFG面積,則四邊形AEIG面積=正方形CEFG面積。

For those who can't read Traditional Chinese, here is the translation that is worded slightly different from the literal one:

Notice that A C , G E and F I are parallel to each other. Then, Δ A E G and Δ C E G have the same areas; Δ E I G and Δ E F G have the same areas. In this case, the area of quadrilateral A E I G is the area of the square C E F G .

Log in to reply

Thanks for translating. That's a great solution.

Log in to reply

Not a problem. It is really my first time, doing this here. :)

Fun fact: I work out with various of languages, not only in Chinese! I can understand and use French and German, which are both useful in modern mathematical articles. :)

Log in to reply

@Michael Huang – Amazing but how did you learn this?

Log in to reply

@James Bacon – I was influenced by my math college years when I was studying various of technical terms coined from European, Russian and Asian mathematicians. Some modern articles were written in the languages I already mentioned, which is why I became more interested in understanding how statements are formed, much like how patterns are formulated. :)

Yeah me too.

Besides the upvotes (which simply push the solutions to the top), I consider this solution to be the best so far due to more geometry involved.

I like solving with various of methods. However, I prefer to post the most elegant method at any level. Seems like I am not the only one who prefers to avoid textbook-like methods not taught here!

Log in to reply

@Michael Huang – I agree. Do you know if there's a name for this technique/theorem?

Log in to reply

@Garoh Seven – Robert mentioned the following theorem already:

The area of a triangle is 1/2 base x height. The base of all the of triangles is GE. Look carefully and you should be able to convince yourself that the heights are all the same.

Isn't math beautiful in all languages? Thank you for the translation too.

Log in to reply

Yes, that is certainly true. Though, it is popular in some countries. Besides Wikipedia (which has a lot of translated articles into separate languages), it is difficult to find scholarly articles of rare languages, such as Urdu or Hindi. While I was in my non-math job, I independently pursue my interest in different subjects for more than 4 years (since my college graduation).

Is this a theorem? How are those areas equal?

Log in to reply

The area of a triangle is 1/2 base x height. The base of all the of triangles is GE. Look carefully and you should be able to convince yourself that the heights are all the same.

Just to clarify, EG is a common base for the 2 pairs of triangles, and the common heights (SQRT 32)/2 are the perpendicular distances from EG to FI and EG to AC. Well, I cheated, just estimated (guessed) the dimensions of the various squares and calculated the answer as more than 16 but less than 17, therefore not 15 nor 18. .

Thanks a lot!

FYI In your translation, it's not that all 4 triangles have the same area. It's that the first 2 and the second 2 have the same area.

Log in to reply

Perfect! Missed the small part of the original text. :)

That's awesome! I used algebra, but I like this solution better!

Very beautiful solution!

Ah, that's beautiful!

can some one explain why those lines are parallel?

Log in to reply

There are all diagonals of squares. So all are at 45 degree angles to the sides.

nice!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Note: The figure is not drawn to scale.

Let

A

B

=

a

and

H

E

=

b

, then

H

I

=

I

J

=

4

−

b

and

D

G

=

a

−

4

.

Note: The figure is not drawn to scale.

Let

A

B

=

a

and

H

E

=

b

, then

H

I

=

I

J

=

4

−

b

and

D

G

=

a

−

4

.

a r e a [ A E I G ] = a r e a [ A B E I J G D ] − a r e a [ A B E ] − a r e a [ G J I ] − a r e a [ A D G ]

a r e a [ A E I G ] = a 2 + 4 2 + ( 4 − b ) 2 + 2 1 ( b ) ( 4 − b ) − 2 1 ( a ) ( a + 4 ) − 2 1 ( a ) ( a − 4 ) − 2 1 ( 4 − b ) ( 4 + 4 − b )

a r e a [ A E I G ] = a 2 + 3 2 − 8 b + b 2 + 2 b − 2 b 2 − a 2 − 1 6 + 6 b − 2 b 2

a r e a [ A E I G ] = 3 2 − 1 6 = 1 6

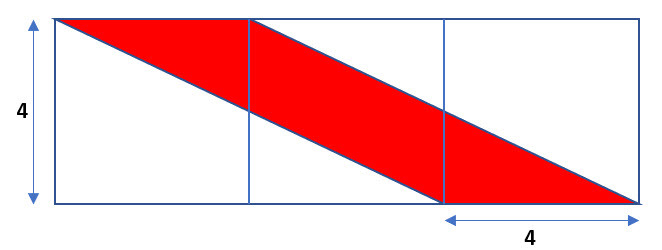

Using the limiting case and logic:

In the limiting case where the side squares’ sides go to zero, we just end up with the middle square as the red quadrilateral. The answer must be independent of the size of the side square, so the answer must be 16.

Same reasoning here, except I took the limiting case where the leftmost square has the same size as the middle one (since I was not sure what the red quadrilateral should be if the leftmost square were to be a point.

Log in to reply

You can also take the case where all square have the same size (as pointed below by Ben Mitchell).

This. Assuming an answer exists can lead to much simpler solutions.

The assumption that they are different squares is a red herring. The answer appears independent of the relative sizes, and taking the limit as each square approaches that of the middle settles that.

So, assume all squares are the same size. Once done the red section becomes a parallelogram with base 4 and height 4. Trivial isn't it?

That was exactly my reasoning. Took all of two minutes, including redrawing the figure and considering the limit.

It is clear from the question that the area is expected to be unrelated to the size of the right and left squares. So imagine their sizes are both zero. It is immediately obvious you remaon exactly with the area of the middle square, which is 16.

Let the bottom left hand corner of the middle sized square be at the origin of the Cartesian plane. Let the big square have side length b and the small square have side length s. Then it is easy to see that the coordinates of the required quadrilateral are in clockwise order, (-b,b),(0,4),(4+s,4-s) and (4,0).

Apply the marvellously simple shoelace formula to these coordinates to see the side lengths of the big and the small square vanish in a puff of logic leaving the answer 16.

Knowing that the red area doesnt change with the size of the adjacent squares. (Cant't because there is no information about them) Minimize the adjacent squares. Only the square in the middle is left.

See all those guys doing all that math. If this were a timed test, they would have wasted altogether too much time. The quiz didn't offer "Not enough information to answer" as a choice, so one of those must be a solution. Since they didn't specify the sizes of the other squares, then the solution doesn't depend on them, so make those sizes something convenient. Make the larger square equal to the middle square and make the sides of the smaller square zero. The solution is now quite obvious.

Given that the question has an answer independent of the sizes of the larger or smaller squares, it suffices to calculate a numerical solution to one special case e.g. when all three squares are equal.

It's plain to see that in such a case the quadrilateral is a parallelogram with area equal to the center square. Thus answer must be 16.

There is no way to determine the size of the other two squares. So if the question makes sense then the answer must be the same whatever their sizes. Assume they are 0. The answer is 16.

The problem statement learns us nothing about the size of the external squares. The possible solutions are all integer. Therefore I conclude that the solution is independent of the area of the external squares. (Which indeed has been proven in earlier solutions - it all cancels out).

So let us reconsider the problem with three equal squares:

The red figure then simply becomes a parallellogram. Its area is Base (4) * Height (4) = 16

The red figure then simply becomes a parallellogram. Its area is Base (4) * Height (4) = 16

Let the side length of the large square be a and that of the small square be b . We have no information about a and b , they can have any value, yet the problem asks for a fixed solution.

So, the answer is independent of the values of a and b . Let's look at the border case a = 0 and b = 0 . In this case, all we have left is the center square, it coincides with the red area, which is 16.

What we know:

1) Triangles that have the same base and height are equal in area

2) The middle square (quadrilateral BCEF) = 16

According to 1), triangle ABF is equivalent to triangle AEF

Both triangle ABF and triangle AEF include triangle AFG within themselves, therefore triangle ABG has an area equivalent to triangle EFG

Similarly, triangle BCH has an area equivalent to triangle DEH

Since

triangle BCH and triangle EFG, and quadrilateral BHEG = quadrilateral BCEF and

quadrilateral BCEF = 16 according to 2)

we can deduce that triangle ABG, triangle DEH, and quadrilateral BHEG (what we are looking for) has the same area as the Square in the middle; 16.

Sincere apologies to the color blind...

This is the proof I discovered! I was going to post, but you beat me to it.

I used the way of the cheater to quickly find the solution, lol. I'll tell you how.

The middle square is the only one that has fixed dimensions, so your conclusion must be indifferent to the sizes of the squares on the edges.

I know that in this situation the red area is clearly 16.

So, it must be still 16 with a bigger left square and a smaller right square (plus the corner triangle, that becomes a line when all the squares have the same size).

Either this is true or the question has no answer. They should have added "Depends on the sizes of the other squares" as an alternative among the answers to prevent this cheat.

So, it must be still 16 with a bigger left square and a smaller right square (plus the corner triangle, that becomes a line when all the squares have the same size).

Either this is true or the question has no answer. They should have added "Depends on the sizes of the other squares" as an alternative among the answers to prevent this cheat.

The problem can be solved with deductive reasoning. Since no measurements are given for the two squares adjacent to the known square, we can conclude the solution must work for all sizes of the adjacent squares. By shrinking down each adjacent square to a point (area = 0) at opposite corners of the middle square the quadrilateral fills the middle square while occupying no area in the adjacent squares.

Since the measurements of the adjacent squares are arbitrary, the area of the quadrilateral will be equal for all measurements of the adjacent squares. Then assume the adjacent squares to be equal to the mid square. Now the quadrilateral is a parallelogram with base =4 and height =4. Thus, area of parallelogram =4*4=16

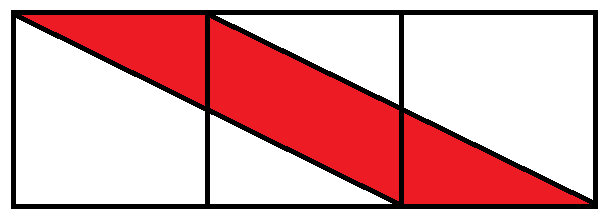

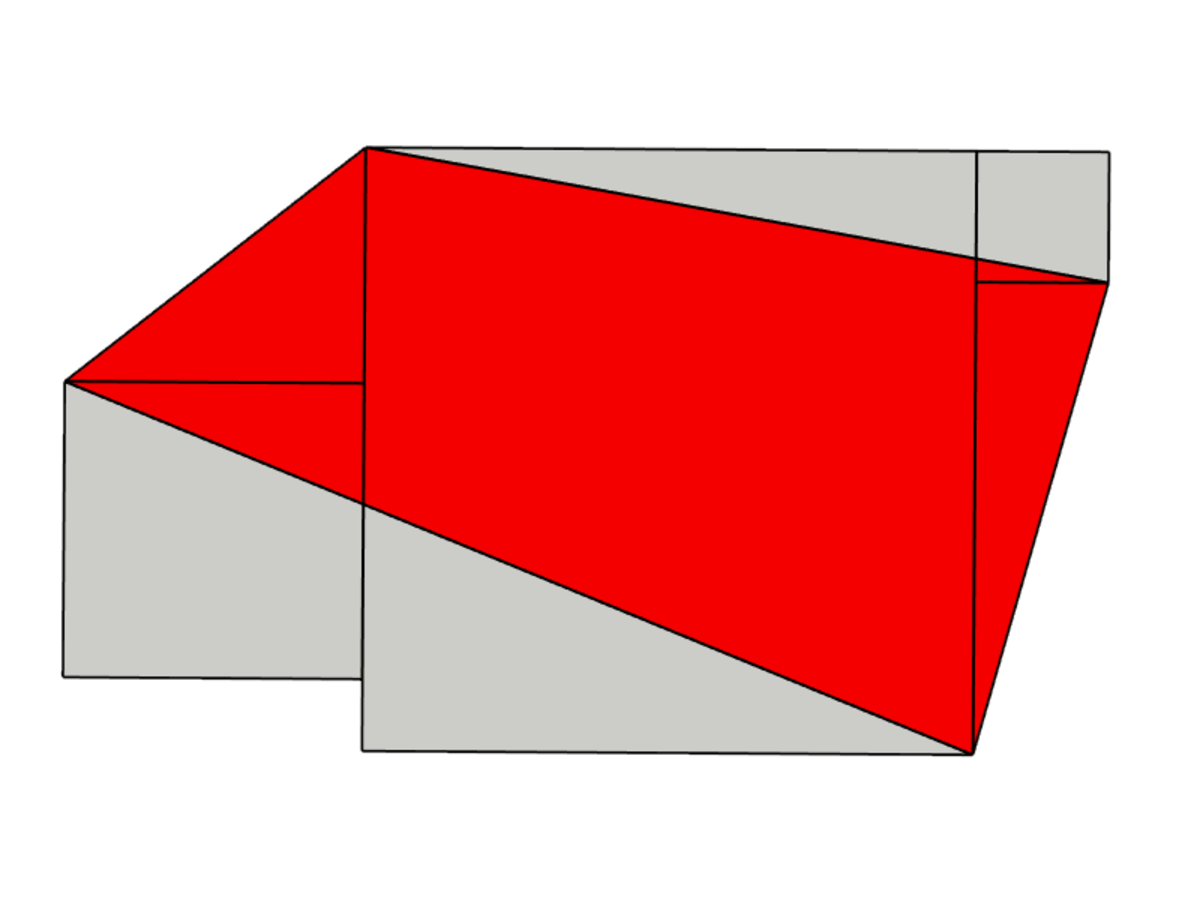

The solutions provided are only valid if the squares have common CORNERS. The text of the question only stipulates common sides. If a configuration such as:

is made then the solution is not the same as the area of the central square.

is made then the solution is not the same as the area of the central square.

Good point!

I multiplied 8 by 2 and got 16.

......revolutionary.

Since the problem did not specify the relative sizes of the three squares, the answer must be independent of their sizes. Taking them all to be the same size it becomes a simple application of the area of a trapezoid with known base and known altitude.

Yes, but the real challenge would be to prove the answer holds regardless of the relative sizes. I have discovered a purely geometrical proof of this, which I'll post if no one else already has.

If all square are the same, the answer is 16. So...

This is not a rigorous solution!

Let the sides of the outer squares be a and b , a ≥ 4 ≥ b . The statement doesn't provide enough information to determine the value of a and b and the answers suggest the result does not depend on a or b .

If we choose convenient values for them (f.e. a = 4 and b = 4 or b = 0 ), the red quadrilateral turns into a shape with known sides and whose area can be easily computed. For a = 4 and b = 0 the red shape is a right triangle with sides 8 and 4 ; its area is 2 8 × 4 = 1 6

Since the problem doesn't mention the size of the squares on the sides, it suggests that their sizes don't matter. So let them both be 4x4 as the central square is, then its obvious that the red quadrilateral is also 16 in area.

What if, instead of squares ,it is circles. How different will the solution be?(after all area of circles is pi r square)

You can complete the middle square by using the red pieces

More intuition than math : Let a be the length of the big square and b that of the small one. Since we have no information whatsover about a and b (and they can therefore be any size), let : a = 4 a n d b = 0 Doing so we get 2 squares side by side (the little one disappears and the big one becomes the size of the medium one). We then have a red square triangle half the area of the 2 squares. ( ( 4 + 4 ) ∗ 4 ) / 2 = 1 6

This may be cheating, somewhat, but based on the way the problem was worded, I inferred that it didn’t matter how large the other squares were, and the answer would be the same no matter what. Therefore, we can set the side lengths of both of the other squares to 4, giving us a parallelogram of height 4 and base 4, and an area of

| 16 |

Examine the limts. If the large square has side length a and the small square has side length b then as a tends to 4 and b tends to 0 the diagram becomes a rectangle of size 8 horizontally by 4 vertically divided diagonally in half giving an area of the top half triangle of 16. Similarly, if a tends to 0 and b tends to zero the diagram becomes the central square of area 16.

Without loss of generality, the solution must be the same as the three squares become the same size and have the same area, and this remains the same as the area of the whole square in the middle.

We don’t have sizes of the big and small square. It means that area of the red region doesn’t depend on those sizes. Make those squares equal to the middle square. Then the area of the red region is 4*4=16.

The sizes of the larger and smaller squares are not given, the result is therefore invariant on these values.

Let the larger and smaller squares be of side length 4, In this case the required area constitutes a parallelogram of parallel side length 4 and height 4

Thus area = 4 x 4 = 16

The centre square is made up of a red band and two white triangles. The big square on the left contains a red triangle.

Statement 1: The area of the red triangle in the big square is equal to the bottom white triangle in the centre square.

Statement 2: The red area to the right of the centre square is equal to the top white triangle in the centre square.

It follows that the complete red area in the diagram is equal to the area of the centre square.

Proof of Statement 1:

Let the side of the centre square be c, and the side of the left hand (big) square be b. Consider the line from the top left corner of the big square to the bottom right corner of the centre square. This line intersects the vertical line common to the two squares. Let the distance from the bottom of the diagram to the intersection point be x.

Considering similar triangles: x = bc/(b + c).

Area of the bottom white triangle = ½ cx = ½ bc^2/(b + c)

Area of left red triangle = ½ b(c – x) = ½ b(c – bc/(b + c)) = ½ b (c2^/(b + c)).

Statement 2 can be proved in a similar way.

Therefore the red area is equal to the area of the centre square which is given as 16.

As we are not given the areas of the two squares, there must be a general solution for all possible areas. Condition is left square aligned with bottom of middle square, right square with top. General solution includes squares of side 0. If squares are of size 0, red shaded area becomes full middle square = 16.

Consider that there is no information on the size of the outer squares, therefore, given the answers are numbers not equations, one can infer that it doesn't matter what size they are, the answer is invariant. So make the squares size zero. Then the top right of the quadrilateral becomes the top right of the central square, the bottom left becomes the bottom left of the central square, and the other two corners were already top left and bottom right of the square. The quadrilateral and square are now the same shape so have the same area.

Somewhat cheating solution (assuming that there is an invariant answer instead of proving that it is invariant):

The areas of the larger and smaller squares are not given, therefore we can assume that the answer does not depend on those sizes, and the area will remain the same if those sizes vary. So we can set those areas to be 16 also, giving a vastly simplified parallellogram as the red area with base and height equal to the middle square. Thus the area is 16.

A quad = Area of 3 squares a 2 + 1 6 + b 2 − △ yellow 2 a ( a + 4 ) − △ blue 2 a ( a − 4 ) − △ green 2 b ( b + 4 ) + △ pink 2 b ( 4 − b ) = a 2 + 1 6 + b 2 − 2 a 2 + 4 a + a 2 − 4 a − 2 b 2 + 4 b − 4 b + b 2 = a 2 + 1 6 + b 2 − a 2 − b 2 = 1 6