A geometry problem by Ajay Sambhriya

In triangle

A

B

C

,

∠

A

B

C

=

9

0

∘

.

Square

A

C

D

E

with center

O

is drawn externally on side

A

C

of the triangle.

If

O

B

=

1

0

, what is the area of quadrilateral

A

B

C

O

?

The answer is 50.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

12 solutions

Moderator note:

Seeing isn't always believing. Despite the great pictorial proof, there's a concern that it might not give us exactly what we want.

Going from the setup to the original problem might introduce an assumption about the placement of points, or the way that things fit, etc. An example of such a scenario allows us to prove that every triangle is isosceles. We can do "go from the original problem to this setup" via

Given O A B C , consider a square with side length A B + B C (extended suitably).

Claim: O is the center of the square. (Fill in the details)

Hence, we conclude that the area is ...

This is good... There are3-4 other ways to solve this problem

Thanks the answer well written. Kudos to you:)

I am not convinced this is correct. How do you know A B C O is one-fourth of F G H B ?

Log in to reply

Angle ABC = 90 (given) Angle AOC = 90 (bisecting diagonals of square) So, with AC as a diameter of a circle, right triangles would touch circle's circumference and also would have equal areas. Hence, ¼ of square ACDE, i.e. triangle AOC has same area as triangle ABC. And, same goes for other three ¼ of square ACDE. Hope, I am able to explain.

Log in to reply

That's not really obvious. I suggest that the solution writer add an explanation to explain that, otherwise, the solution is missing a rather big step, which makes it harder to follow through.

Log in to reply

@Pi Han Goh – Maybe @Vikas Kharakwal 's description is not, or makes the situation seem more complicated than it is, but it really should not be hard for someone to see that the large square is composed of four triangles congruent to △ A B C and four triangles congruent to △ A O C .

Log in to reply

@Dan Ley – While I agree that the resultant setup is a great pictorial proof, the slight concern is with showing how to go from the original problem to this setup, as opposed to from this setup to the case of the original problem. The concern is that going from the setup to the original problem might introduce an assumption about the placement of points, or the way that things fit, etc. An example of such a scenario allows us to prove that every triangle is isosceles.

We can do "go from the original problem to this setup" via

- Given O A B C , consider a square with side length A B + B C (extended suitably).

- Claim: O is the center of the square. (Fill in the details)

- Hence, we conclude that the area is ...

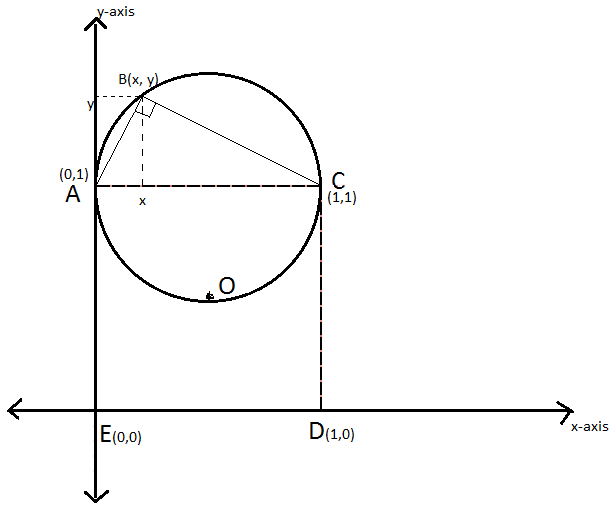

Using the Distance Formula, we can write an equation for the line segments AB and BC.

A B = ∣ y − 1 ∣ 2 + ∣ x − 0 ∣ 2 ⇒ A B = x 2 + y 2 − 2 y + 1

B C = ∣ y − 1 ∣ 2 + ∣ x − 1 ∣ 2 ⇒ B C = x 2 + y 2 − 2 x − 2 y + 2

It is important to note that the lines AB and BC are perpendicular to each other since they form a right angle.

And we know that the product of the slopes of perpendicular lines is -1.

m A B = x y − 1

m B C = x − 1 y − 1

m A B ⋅ m B C = − 1

x 2 + y 2 = x + 2 y − 1

Let's use this equation to simplify the A B and B C .

A B = ( x 2 + y 2 ) − 2 y + 1

A B = ( x + 2 y − 1 ) − 2 y + 1

A B = x

From the figure above, we know the equation: x 2 + y 2 = A B 2

Substituting..

( x 2 + y 2 ) = A B 2

( x + 2 y − 1 ) = ( x ) 2

x + 2 y − 1 = x

y = 2 1

x = 2 1

Hence the ordered pair of point B is ( 2 1 , 2 3 ) .

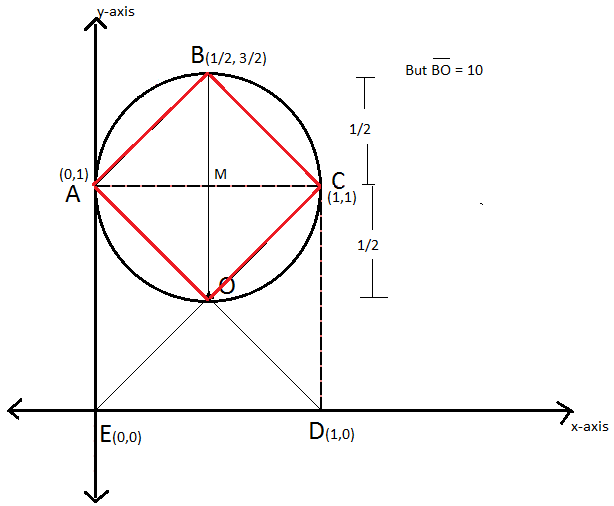

So, to write a more specific drawing, we have this:

The line B O is a vertical straight line.

Since we used a unit circle in representing the problem in Cartesian Plane, the length B O has a factor.

The length of B M and M O adds to a total of 1.

And according to the problem, B O = 10

Therefore, there is a factor of 10. Let's call this k = 1 0

Also, if A C =1, then its actual measurement is k times A C .

k ⋅ A C = 1 0

B O and A C are the diagonals of the square A B C O .

Area of the square using the diagonals = 2 d 1 d 2

Area = 2 ( 1 0 ) ( 1 0 )

Area = 5 0 c m 2

This is a very neat solution! Coordinate geometry is almost guaranteed to work for any high school geometry question.

I'm confused. You seem to have proven the only point on the upper semi-circle is (1/2/,3/2). That's clearly not true. I don't feel like digging through the details to find the mistake, but there must be one. (FWIW, if you're lazy like I am and only care about finding a solution without proving that the solution is unique, fixing a point at the mid-point of the arc makes for much simpler approach! After all, it forces the quadrilateral OABC to be a square!)

Log in to reply

Hello. It is not explicitly stated that point B is at the midpoint of the arc that's why I used an arbitrary location B ( x , y ) .

It just so happen that after finding the equations (using slope and the distance formula), that the point B is actually at the midpoint of the arc: B ( 2 1 , 2 3 )

(Note: For simplicity, I used 1 unit as the side of the square. That, being the diameter of the circle, as well)

Also, the points A ( 0 , 1 ) , C ( 1 , 1 ) , and O ( 2 1 , 2 1 ) (being the intersection of the diagonals of the square A C D E with side equal to 1) tell us that the quadrilateral A B C O is, indeed, a square .

Now, if you have that high level of confidence to assume that A B C O is a square without actually proving, then go ahead. It is not necessarily incorrect. However, to convince other solvers of your answer, you may want to provide your COMPLETE solution/proof. :)

Log in to reply

I found the mistake. You state that from the figure above, we know the equation: x^2+y^2 = [distance(a,b)]^2.

But when I review that figure, clearly: x^2+(y-1)^2 = [distance(a,b)]^2.

Log in to reply

@Wes Pinchot – I think the word "mistake" is an overstatement. Now, although I did not show all parts of the solution, I viewed the next image such that the diameter of the circle is the x-axis. That's why I was able to assume that x = 2 1 and y = 2 1 .. But you'll find that the ordered pair of B O is ( 2 1 , 2 3 ) and N O T ( 2 1 , 2 1 ) . I added the length of the square, which is 1. So 1 + 2 1 = 2 3 . I just failed to S H O W all parts of the solution and that does not mean it's a mistake. Thanks for noticing it, though. :D

Log in to reply

@Isaac Lu – Joven, you're missing the point. x=1/4 and y = 1+sqrt(3)/4 should ALSO be an acceptable solution. Basically, any point on the upper semicircle should be.

EDIT: Nevermind this 2nd paragraph, i was wrong about it.

- And i think i might've found another mistake... How did you get from m A B ⋅ m B C = − 1 to x 2 + y 2 = x + 2 y − 1 ?

But i still fail to see how you get from x 2 + y 2 = E B 2 to x 2 + y 2 = A B 2 ...

Let's put a pont F at the middle of line AC. Let AF=FC=r. Note that r is a radius of a circle that has ABCO inscribed. Using triangle BOF and law of cosines we write 10^2=2r^2(1+sin2A) where A is the angle BAC. This is because angle BFO=pi/2+2A. The area of ABCO is P=r^2+(2r sinA)(2r cosA)/2=r^2(1+sin2A) which is 100/2=50. We used that area is a sum of areas of triangles ABC and ACO. In general, area is always (OB^2)/2.

It seems difficult to follow your idea without a diagram. Maybe you could attach a diagram with your solution? :)

I liked the fact that you have generalized your solution

Sorry. I'm new to this site. Still figuring how to use it...:)

Log in to reply

Here's how you do it:

Click on the third icon and select the image from your computer.

Surely, the problem is fairly trivial and the diagram is misleading. B lies on the circumference of a circle, centre O, radius 10. Since angle ABC = 90˚, B also lies on a circle, centre midpoint of AC (say F) and radius 5. O, F, B are collinear and the quadrilateral ABCO is a square with side length 5√2. The area is therefore 50.

Log in to reply

Except OFB are only colinear when AC=10 also... But if it's not, the diagram is not misleading.

We can also use the law of cosine and sine to find the solution:

(1) A B 2 = A O 2 + B O 2 - 2 * AO * BO * cosAOB

(2) B C 2 = B O 2 + C O 2 - 2 * BO * CO * cosBOC

(3) AOC is a right triangle and AO = CO = 2 2 AC

(4) We also know triangle ABC is a right triangle and A B 2 + B C 2 = A C 2 , from (1), (2) and (3) we can derive the following equation:

A C 2 = 2 1 A C 2 + 100 - 10 2 * AC * CosAOB + 2 1 A C 2 + 100 - 10 2 * AC * CosBOC

=> 2 * AC * (CosAOB+CosBOC) = 20

(5) According to the law of sine, the area of triangle AOB = 2 1 * AO * BO * SinAOB and the area of triangle BOC = 2 1 * BO * CO * SinBOC

(6) Since AOC is a right triangle, then CosAOB = SinBOC and CosBOC = SinAOB => CosAOB+CosBOC=SinAOB+SinBOC

(7) Therefore, area of ABCO = 2 1 * 2 2 AC * 10 * (CosAOB+CosBOC) = 2.5 * 2 * AC * (CosAOB+CosBOC)

(8) Finally, from (4), the area of ABCO = 2.5 * 20 = 5 0

Nice solution! I liked how you have used various properties of triangles such as Pythagorean theorem, cosine rule and area of triangle using sine rule to eliminate all side lengths except A C .

I see that we did not explicitly found the value of A C . Is it possible to find A C if it is unique?

I just want to know why .5 * 10 * 10(from the quarter of the square, and 10^2 / 4 is plausible as well) + .5 * 6 * 8(pythagorean triple when 10 is the hypotenuse) = 49 is not acceptable.

I don't understand your solution. Can you clarify how "Area ABCO = Area EBDO (square) with diagonal"?

I think by adding that explanation, more people would be able to understand your solution.

Very nice question / setup!

Given that 2 is the only digit in your problem, an answer of 2 is easily guessed. Can you suggest alternative values? E.g. Set OB = 10, with an answer of 50.

Log in to reply

But then i have to change the solution as well.

At first glance, there isn't enough information to solve the problem, because angle ABO cannot be determined. Given that a unique solution exists without this information, I am free to draw the figure any way I please. I choose BO as the bisector of AOC. Given that ABC is a right angle, then ABCO is just a square with diagonal 10. Pythagoras gives the side of that square as 5sqrt(2), and area 50. Note that we weren't asked to prove that this answer holds for all angles ABO

Me either. It was the easyest way. Even easier making B coincident with C

Consider BC and BA as a part of diagonals of square say ACFG drawn aside ACDE.

Let AC=x

Therefore

FC=x

AD is diagonal.

AD=(root 2)x

AO=OC=x/(root 2)

(AO=AD/2)

Similarly.

BC=BA=x/(root 2)

Therefore.ABCO is square

Area=(x square)/2

Now. From B and O draw perpendiculars BM and ON on FC and CD respectively

Therefore.

MC=CN=x/2 MN=MC+CN=x

But.MN=OB

x=10 Therefore. Area of square ABCO=50. (Ans)

Let AB be y, BC be y, AO and AC be r.

By Pythagoras' Theorem , x² + y² = 2r², and AC = r√2

Then by Ptolemy Theorem , xr + yr = 10(√2)(r) ⇒ x + y = 10√2

By squaring both side we get x² + y² + 2xy = 200, sub x² + y² = 2r² into the equation and get r² + xy = 100

Since it ask for area, area of ABCO = (r² + xy)/2 = 100/2 = 50

I think there are several minor typos here:

1. I think you meant AB = x* instead of y?

2. AO and OC* be r.

You used Ptolemy Theorem, which suggests that ABCO is a cyclic quadrilateral . Can you explain a little on how you got it as a cyclic quadrilateral in the first place? Otherwise, good solution!

Since angle ABC is given as 90 degrees, we know that side AC is the diameter of a semicircle which circumscribes triangle ABC. Since ACDE is a square, symmetry conditions demand that all 4 angles around O are identical, 90 degrees also. The altitude of triangle AOC passes through P, the bisector of segment AC, and is by definition perpendicular to AC. As O is the center of the square, symmetry requires that the altitude just drawn have a length of 5. Since P is the center of the circumscribed circle (for both right triangles), the distance to points A, B, C, and O is the same for all four, 5. Since OP + PB = 10, the Law of Cosines requires that the three points must be collinear, and the two triangles are congruent, with a total area equal to 1/2 of the square, ACDE, 50.

This looks about right. By drawing a figure, one can better understand what you're trying to say.

Would you like to add an accompanying image that illustrates what you've described in your solution?

Angle AOC = 90° And side AD = side AC (diagonals of square bisect each other at 90°)

And given that angle ABC = 90° Which implies ABCO is a square whose diagonal is OB .

Let a be the side of the square ABCO , so OB = a 2

Or a = OB / 2 = 2 1 0

Now Area(ABCO) = a 2 = 50

ABCO isn't necessarily a square, because all we know is that 2 adjacent sides are equal and 2 opposite angles are right angles. It can be (rather, it is) a cyclic quadrilateral with AC as diameter, and ABC and AOC as the 2 right angle triangles inscribed in the circle, with AO=OC. It cannot be assumed that AB=AC. They can be different.

ABCO clearly isn't a square. Not in the picture above. You can add the assumption to quickly find what the solution must be , but doing so skips over the proof that the solution for the square generalizes to all quadrilaterals.

Kanad is right, you can't just assume that BAO and BCO is a right angle because the question didn't specify that. Do you know how to fix your solution?

c o n s i d e r A B = x , B C = y since B+O=180 so A,B,C,O are cyclic . we can use ptolemy’s equality A C . B O = C O . x + A O . y o r , 1 0 A C = ( x + y ) A O [ since A O = C O = 2 1 A C ] o r , x + y = 1 0 2 o r ( x + y ) 2 = 2 0 0 o r , x 2 + y 2 + 2 x y = 2 0 0 o r , A C 2 + 2 x y = 2 0 0 [ since x 2 + y 2 = A C 2 ] o r , A C . 2 A C . 2 + 2 x y = 2 0 0 o r , A C . h . 2 + 2 x y = 2 0 0 [ if AC is considered as base the height of Δ A O C = h = 2 A C ] o r , 4 ( 2 1 A C . h + 2 1 . x y ) = 2 0 0 o r , 4 ( Δ A O C + Δ A B C ) = 2 0 0 o r , 4 A B C O = 2 0 0 o r , A B C O = 5 0 which is the area :)

consider the direction of axes along AC and CD with origin at C, and the problem simplifies as followed:-

Proof for Pythagorean Theorem springs to mind.

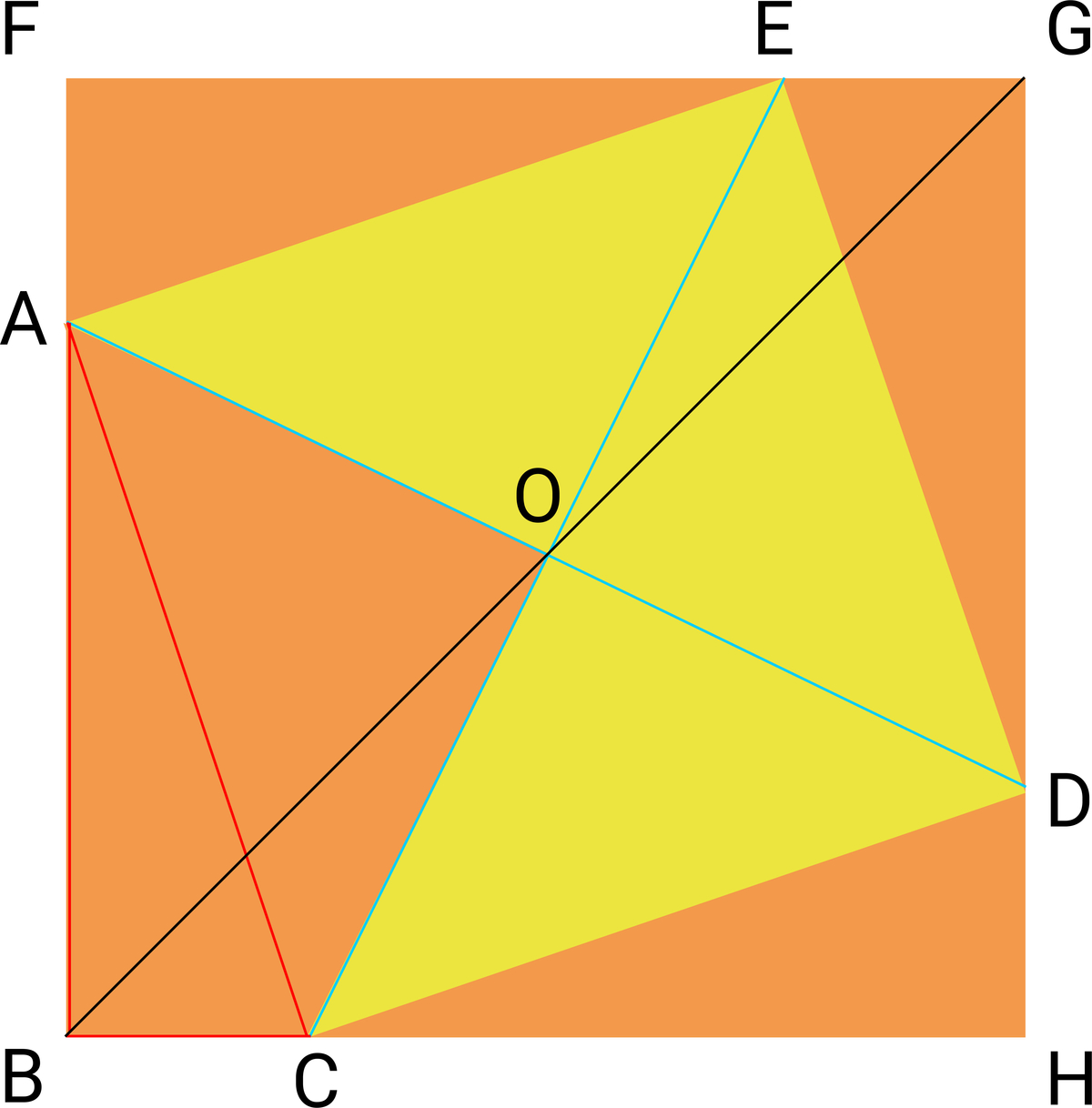

We can form a larger square of sidelength A B + B C , with one corner at B . The diagonal length

B

G

=

2

0

, so the area of the large square

F

G

H

B

=

2

2

0

×

2

0

=

2

0

0

.

The diagonal length

B

G

=

2

0

, so the area of the large square

F

G

H

B

=

2

2

0

×

2

0

=

2

0

0

.

The area of quadrilateral A B C O = 4 2 0 0 = 5 0 .