Bishop Attack

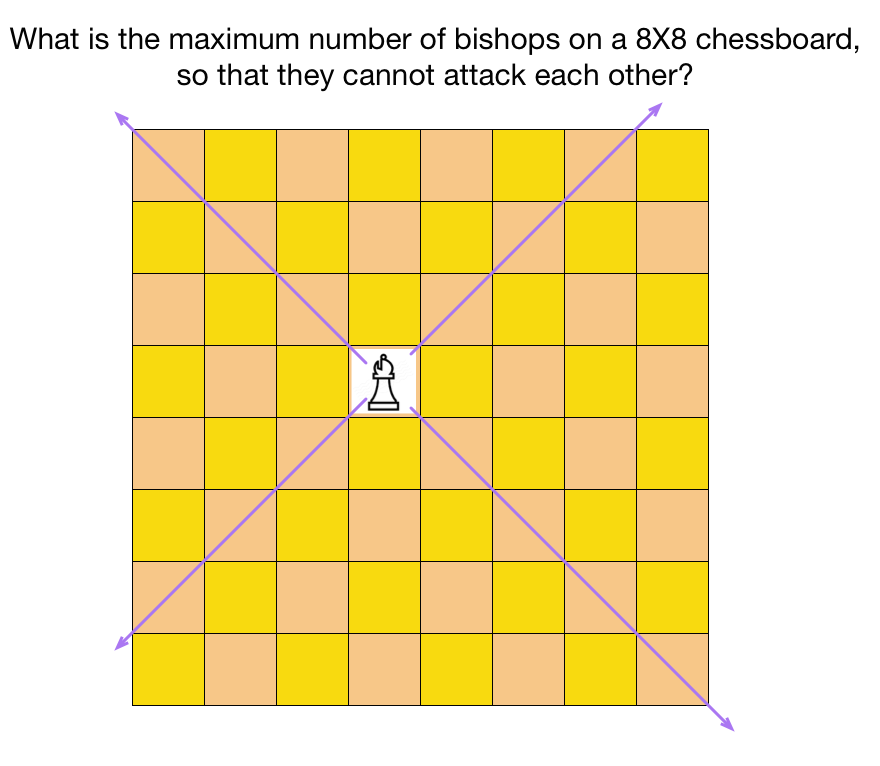

What is the maximum number of bishops on a 8 × 8 chessboard, so that they cannot attack each other?

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

3 solutions

Oh , that's another way of thinking at the possible synthetic combination of the way bishops attack each other in an abstract way by considering coordinates as the expression of attacks. But maybe I'm not clear on what I mean so I'll explain briefly.

Taking a number of n bishops observe that in order to say if a configuration where they do not attack each is possible or not there must be an understanding of their possible ways of attacking which can be done in a concrete (taking them by their positions and understanding how they affect the configuration) or abstract way by considering rather than this positions some characteristics which might not imply any kind of constructive approach but which will refer to this concrete ways by considering those characteristics themselves. This kind of understanding of the ways of attacking each other further is a composition of the concrete way single pieces attack and therefore the understanding considered must speak of the composed attack of all the n pieces on the board which is done as I said either concretely or abstractly and in your solution what you do is to speak of exactly this composed attack of the pieces when you observe that for two bishops to attack each other they must have the same coordinates. Actually what makes the problem difficult , the fact that the pigeonholes are not always evident as you said thought the general approach is directly implied in the question , is this understanding of attacks which is composed that is not perceived acutely enough because it is not obvious how the n bishops work so that they make possible attacking configurations. In your solution you observed a regularity about the composed attack of them but more important you expressed the synthetic attack of the n bishops itself firstly in some terms , these being the "coordinates holes" that made possible thinking at the attack and this abstractly without constructive additions. In a constructive approach it is met the same problem of expressing the composed attack. However in considering an approach that is constructive the expressed synthetic attack will maybe imply at some point abstract considerations that can deviate from the concrete terms in which it has been thought because it's synthetic itself but nonetheless I still believe that , while indeed not necessary , a constructive approach would make the understanding of the synthetic attack and of any possible configuration by it's concreteness better and if what is wanted is this more articulate understanding of a problem and not just a desire to prove something as fast and explicit as it can which to me is in general what I believe mathematics should be a constructive approach maybe tells more but beautiful problem anyways for both reasons , that of understanding deeper and of being delighted.

Yes, it seems that if there are 13 bishops satisfying, we can always place 14th bishop

The maximum Number of bishops on a

8

×

8

Chessboard is 14.

I don’t think we can place 16 bishops, i have tried every single possibility

You've shown that 14 can be achieved. How can we show that 14 is indeed an upper bound, in order to establish that it is the indeed the maximum?

@Abhay Tiwari You should appreciate this, and realize that the solution is incomplete.

Log in to reply

Yes I see it's incomplete. But I am not able to prove it. Please guide us sir!

Log in to reply

Essentially, we're applying the pigeonhole principle , and so you must find the relevant pigeonholes to use.

In the case of the knight problem, I had 32 pairs of squares, and so if we had 33 knights then 2 knights belong in the same pair and thus attack each other.

Do something similar here. Find 14 "pigeonholes", and so if we had 15 bishops then 2 bishops belong in the same "pigeonhole" and thus attack each other.

Log in to reply

@Calvin Lin – How do we know that there are only 14 pigeonholes ?

Log in to reply

@Sabhrant Sachan – This should be interpreted as "If the naive pigeonhole principle argument were to work, then we would have 14 pigeonholes". Here is the logic behind the number:

Say that we want to apply the pigeonhole principle. We know/suspect that when there are 15 bishops (pigeons), then we want to find 2 bishops which can attack each other. Let's say that the number of holes is H. Then, we must have ⌈ H 1 5 ⌉ ≥ 2 , which gives us H ≤ 1 4 .

We also know that when there are 14 bishops, then we need not find 2 bishops that can attack each other. As such, this tells us that ⌈ H 1 4 ⌉ ≤ 1 , which gives us H ≥ 1 4 .

Thus, if this approach were to work, we would strongly believe that there are 14 pigeonholes.

Of course, there is no guarantee that this will work, and it's a hope that it does.

Log in to reply

@Calvin Lin – I think a constructive approach would work better than just applying the pigeonhole principle exactly because using the pigeonhole principle doesn't guarantee that it will work. I suppose that the way of applying the pigeonhole principle is here related with the conceiving of the diagonals which a bishop occupies as the holes such that since every bishop with the exception of the 2 bishops which can be placed in the corner will attack in 2 diagonals therefore being implied that in those 2 diagonals can't be placed any more bishops because they would attack each other and there are 26 diagonals the maximum number of bishops that can be put to should be of 2+24/2=14. It can be said that this type of approach is used generally in those type of questions since they ask about how many pieces of the same type can be positioned and it is implicit in such questions that there will be that a piece which attacks in some way determines the positions of the other. This leads to understanding the way the pieces by their combined positions affect each other but in rather an abstract way not being assured that for that respective maximum , here 14 , there is a configuration of pieces that will work because even if it is assured that for a smaller number of pieces there will be a number of diagonals that are not having any piece on their squares it is not assured that that diagonal has any of it's squares not being attacked since taking any square of the diagonal with the exception of the corner squares they will be expressed as also having some other diagonal which has it common of which it is not know if that other diagonal is attacked or not by a piece. That would imply therefore that in order to know if there is a configuration of n pieces that works possible or not there should be a concrete understanding of the way the pieces attack each other and in more acute way of the way their combined positioning affect the squares which are being attacked. Understanding this way of combined attacks of pieces by their positioning implies therefore it can be said some sort of constructive understanding in which it is know how does a piece in a position affects concretely the squares in the other such that there will be possible to put more pieces after or that there is not.

For achieving such a way of thinking of them and therefore understanding the concrete way pieces combined affect the squares it would be nice to make firstly a way of organizing things which may be considered also as finding a language or some terms in which this is to be thought of and make explicit what is meant by something. Before doing that consider however that since a bishop which is on a square of some color can affect just the bishops which can be putted on squares of the same color for all possible configurations it can be thought that there are two cases of bishop configurations and therefore that without loss of generality and simplifying it can be taken just one of those cases. Afterwards in order to achieve that kind of organization consider either all the rows or all the columns in the board and think for the placing and combined attacks of bishops in this terms. This will , it may be said , give some kind of background structure in which all the possible bishop configurations can be thought of and after doing this consider firstly the combined attacked for any configuration of bishop in terms of rows (or columns but I prefer rows). Based on it's place on a column a bishop will attack a number of squares in different rows and for all the different rows which are attacked by a bishop it can be said that a bishop has a range of rows attacked and for any of this attacked rows by a bishop there will be also a number of bishops which will attack that row. In this terms it can be thought therefore that the combined attacks of all the pieces can be put in terms of the extension over the number of rows of the bishops attacks or that for a number of pieces which have some range over the rows a number of squares in different rows will be covered. Secondly it can be thought of the placings of this bishops in terms of this rows too and be said by this that for a number of rows which are attacked by the combined attacks of some bishops if it is possible that will remain rows which have squares that are not covered there is possible to insert at least one more bishop. In this way it is made explicit the relation between some configuration and the number of bishops which can be placed. Observe that with some thought it can be assured more or less abstractly that for pieces which have specific ranges there will be necessary a number of rows which have all their squares covered and that if the specific task would be to achieve the smallest number of such rows then there would be possible to choose the pieces which have the smallest range of rows such that it will be assured that will always remain some rows if possible which are not attacked while this would not be necessary if there are configurations which have all their rows attacked while still let a number of squares not be attacked in them anyways.

Log in to reply

@A A – I can guarantee you that a nice short PP argument exists, because I have one.

Log in to reply

@Calvin Lin – And it will also assure that apart from setting the upper bound it also works ? Maybe you will want to present it or you will prefer to keep it until someone else founds it. Anyways , it should be pretty cute an argument indeed. Oh , and you mean that it implies this type of pigeonnhole principle ?

Log in to reply

@A A – Yes, the solution will prove that 14 is indeed an upper bound, by creating exactly 14 pigeonholes. Your initial comment came close to the idea, but you got sidetracked by "accounting for everything".

I will post the solution in 2 days time (a week after I posted this initial problem). Am waiting to see if anyone else can figure it out.

Log in to reply

@Calvin Lin – Hmmmm , I can only speculate that it is about wisely selected pairs of bishops. Anyways , that solution in the initial comment still explains pretty much so it's good that account for everything.

@Calvin Lin – Anyways , beautiful problem. And since I have the opportunity let me congratulate you for your beautiful site , you had a good and pretty much inspired idea making it and i'll think at this problem.

@Calvin Lin – Or you can also consider things in another way to pretty much make explicit what the holes actually are. By considering again just one type of bishops (either the ones which are on black or the ones which are on white squares) and taking firstly just the diagonals of one direction it can be said that it will be a number of maximum 7 bishops which should be positioned in any square of this one direction diagonals considered such that they do not attack each other. Observe now than while it is right that however the squares of this diagonals will be chosen they will not affect anything at the diagonals of opposite direction for some choice of squares of a diagonal of one direction it is possible to place bishops such that they attack squares of diagonals of the same direction. Taking this into account observe that since there are 14 pairs of diagonals (one of a direction and another of the opposite direction for each pair) in order to not attack each other a bishop must be placed in just only one pair. That means that if there is to place a bishop it must be placed such that it doesn't attack more than just one diagonal of one direction. But this would imply that all those positions in which a bishop would attack diagonals of the same direction observed before are places which are not correct since they imply that there will be a bishop implied in more than one pair of diagonals and therefore 2 bishops which will attack each other. Is this your argument ? It still does sounds confusing a little to me right now anyways.

I also got the same combination

Log in to reply

Great Minds think alike :D

I just counted and saw that the maximum must be fourteen. LOL🤣🤣🤣

Relevant wiki: Pigeonhole Principle - Problem Solving

Let the chessboard be labelled from ( 1 , 1 ) to ( 8 , 8 ) .

It is obvious that we can get an arrangement of 14 bishops. E.g. Having them in the top and bottom most row of all the columns except the right most.

It remains to show that 14 is indeed an upper bound. Such an argument typically arises from the pigeonhole principle, but it might not be obvious how to do so.

Observe that if two bishops can attack each other on the same top-left, bottom-right diagonal, then the sum of their coordinates is the same. As such, let's create the following pigeonholes:

We're still missing 2 squares, namely ( 1 , 1 ) and ( 8 , 8 ) , which we will place in the same pigeonhole:

Then, if we're given 15 or more bishops, we are guaranteed that there are at least ⌈ 1 4 1 5 ⌉ = 2 bishops that are in the same pigeonhole. It is clear that these 2 will attack each other. Hence, 14 is indeed an upper bound.

Since 14 can be achieved and is an upper bound, thus it is the maximum.

Notes: