Closing f n

f ( x ) = x 3 − 3 x

Find the closed form of f n ( x ) , and then find the number of distinct real solutions of f 1 6 ( x ) = 2 .

Note: f n ( x ) is the n th composition of f , that is, f n ( x ) = n times f ∘ f ∘ ⋯ ∘ f ( x ) .

Bonus: If g ( x ) = 2 + x , find the closed form of g n ( x ) .

The answer is 21523361.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

5 solutions

Thank you for the nice solution. I will try to contribute by writing down the closed form of the solution f n ( x )

f n ( x ) = { 2 c o s ( 3 n a r c c o s ( 2 x ) ) 2 c o s h ( 3 n c o s h − 1 ( 2 x ) : : ∣ x ∣ ≤ 2 ∣ x ∣ > 2

Similarly, for the bonus question, the closed form is:

g n ( x ) = { 2 ∗ c o s ( 2 − n a r c c o s ( 2 x ) ) 2 ∗ c o s h ( 2 − n c o s h − 1 ( 2 x ) ) : : ∣ x ∣ ≤ 2 ∣ x ∣ > 2

I would never have come up with the cosine solutions. Here's how I found the number of solutions.

f ( x ) = 2 has two solutions, x = − 1 and x = 2

f 2 ( x ) = 2 has five solutions, the two solutions to f ( x ) = 2 and three more: the solutions to f ( x ) = − 1 . Their values are not important but they can be seen on this graph.

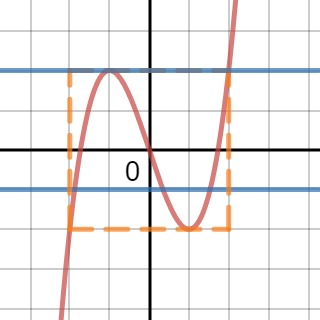

Note the interesting portion of the function is constrained to the orange box. Whenever − 2 ≤ y ≤ 2 , − 2 ≤ x ≤ 2 . This means for each solution to the previous stage there will be 3 values for the next stage with the exception of the solution x = 2 , it only comes from 2 values.

So the number of solutions almost triples from n to n + 1 , falling just one short. Call a n the number of solutions to f n ( x ) = 2 and we have the recurrence, a 1 = 2 , a n + 1 = 3 ⋅ a n − 1 for n > 1 .

I didn't bother finding an explicit formula as this is easy enough to evaluate: a 1 6 = 2 1 5 2 3 3 6 1

Actually your proof give the maximum value of real distinct solution but you don't prove they are all distinct.

Log in to reply

True, but they are all so irrational I assumed they would not be able to overlap except for the x=2. Imagine adding blue lines to the graph. I don't know how to prove it.

Log in to reply

it's not a quesion of irrationality but only geometric, when we start from a point of the graph with an abscyss between ]-2,2[ we can build 3 points by verticaly reaching y=x and select the 3 points of the graph on the horizontal line, then we do it again for each 3 points... by doing so we notice we can only build distincts points on the graph and therefore by starting from (-1,2) we are sur to obtain distincts solutions... it'easy to see "by hand" but i don't have a formal proof either (and i don't like the one with cosinus, i'm sur we can find an aesthetic geometric proof ^^)

The function is continuous and inside the orange box. It oscillates from +2 to -2 only changing sign of the slope when either of these extremes has been reached.

So, between each pair of solutions to f n ( x ) = 2 there are always 2 solutions to f n ( x ) = − 1 , which will turn into new solutions for f n + 1 = 2 . I.e. a n + 1 = 3 ( a n − 1 ) + 2 = ( 3 n + 1 + 1 ) / 2

The tricky part is proving that the function indeed behaves so nicely as I stated in my first sentence. As f n ( − x ) = − f n ( x ) , the number of times the function goes to -2 is identical to the number of solutions to f n ( x ) = 2 . Between each of these maximums and each of these minimums, the function needs to go through -1 somewhere, as it is continuous. But if the function would go from -2 to -1.5 and back to -2, you could have the same number of extreme values while not reaching -1 as often.

Intuitively the function is nicely behaved, and I believe such a local maximum should be contradictory to the degree of the polynomial (we know the number of times it reaches -2 or +2, and this number is already identical to the degree plus one).

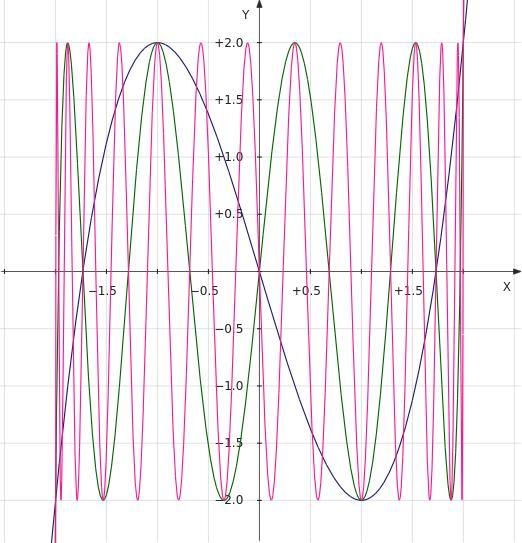

I did think about the cos, but was way too lazy to think through it. It seemed much easier to have a guess which made me make a variant of your idea (I think). So I plotted the graphs of f ( x ) , f ( f ( x ) ) and f 3 ( x ) .

You notice pretty quickly that the roots of f n ( x ) are all real, and when look at f n ( x ) − 2 then all the roots but one become double roots. Since you know the degree of f n ( x ) is 3 n , well you can guess that f n ( x ) − 2 will have 2 3 n − 1 + 1 roots.

let x = 2 cos θ

-

using identity cos 3 θ = 4 cos 3 θ − 3 cos θ , prove that f ( 2 cos θ ) = 2 cos 3 θ

-

the closed form is f n ( x ) = 2 cos ( 3 n arccos ( 2 x ) )

-

prove that :

a. x < − 2 ⟹ f ( x ) < x < − 2

b. x > 2 ⟹ f ( x ) > x > 2

hence all solutions of f n ( x ) = 2 lies within − 2 ≤ x ≤ 2

-

subs x = 2 cos θ , f n ( x ) = 2 ⟹ cos ( 3 n θ ) = 1 , 0 ≤ θ ≤ π

-

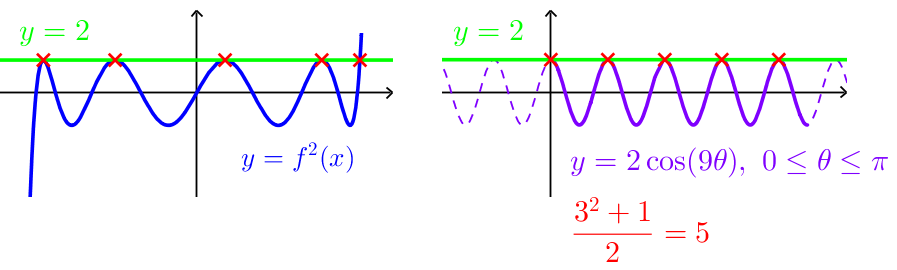

by considering the graph of y = cos ( k θ ) , prove that the number of solutions is 2 3 n + 1

(example for

n

=

2

)

∴ 2 3 1 6 + 1 = 2 1 5 2 3 3 6 1

Bonus: g ( 2 cos θ ) = 2 + 2 cos θ = 2 cos ( 2 1 θ ) , g n ( x ) = 2 cos ( 2 − n arccos ( 2 x ) )

Note: These 2 are related to Chebyshev polynomials , whose iterated functions have simple closed form.

I am sorry, I am not sure I am following. According to my calculations f1(3)=3^3-3 3=18. Do you claim that f1(3)=2 cos(3^1*arcos(3/2)) ? Obviously cos can return a value between -1 and 1 and according to your expression fn(x) can thus be a number between -2 and 2. So how do you get to 18? I shall appreciate if you can elaborate here.

Log in to reply

- by extend cosine function and its inverse into complex number, the closed form works too. ( Inverse trigonometric function )

if you hate complex number, use hyperbolic cosine function and their inverse. (see Chebyshev polynomials )

if you are only interested on number of solutions, it can be proven that no solution lies outside -2<=x<=2 , hence we dont need consider both 1. and 2.

hopefully that helps.

by the way, check this out: 2cos(3^1*arccos(3/2))

Log in to reply

I already computed 2cos(3^1 arccos(3/2)) in Wolframalpha. But if I compute only arccos(3/2) then I get 0.9624236... - and if I computer 2cos(3 0.9624236) then I get -0.9678... - so I don't know how both Wolfram and you sir - get 18. That's what I would like to understand :(

Log in to reply

@Aviel Livay – arccos(3/2) is not 0.9624... but 0.9624 i

from Euler's formula, we can prove that cos x = 2 e i x + e − i x where x can be complex valued.

let y = cos x = 2 e i x + e − i x and solve for x we will get x = arccos y = − i ln ( y + y 2 − 1 ) where y can be outside − 1 ≤ y ≤ 1 or even complex valued.

see more: Inverse trigonometric functions

Let f(1)=x^3-3x, and f(n)=f°f°...f(1), where f is nested n times. We are asked to find number of distinct real zeros of

f(n)-2=0, when n=16,

Let, g(n)=f(n)-2, Thus, we are looking for number of distinct real zeros of

g(n)=0, when n=16,

We show, using Wolfram alpha script "Nest[#^3-3# &,x,n]-2, from n=1,4", that

g(1)=(x-2){(x+1)^2},

{No. of zeros = (1+3^0)}

g(2)=g(1)[{g(1)+3}^2],

g(2)=g(1){(x^3-3x+1)^2},

{No. of zeros=(1+3^0+3^1)}

g(n)=g(n-1)*[{g(n-1)+3}^2],

{No. of Zeros= 1+3^0+3^1+..+3^(n-1)}

Looking at the structure and terms in g(n) for n=1,4, we deduce that number of distinct real zeros of g(n)=0 are given by sum of series

1+3^0+3^1+3^2+....3^(n-1)=(1/2){1+3^n}

which gives for n=16,

Answer=21523361

Warning: This is not a rigorous solution!

The trick with the cosines is the elegant thing to do, but I was way too lazy to think through it. Here is a relatively simple way to guess the solution. I plotted the graphs of f ( x ) , f ( f ( x ) ) and f 3 ( x ) :

You notice pretty quickly that the roots of f n ( x ) are all real, and when look at f n ( x ) − 2 then all the roots but one become double roots. Since you know the degree of f n ( x ) is 3 n , well you can guess that f n ( x ) − 2 will have 2 3 n − 1 double roots and 1 simple root, for a total of 2 3 n − 1 + 1 roots. This gives the answer 2 3 1 6 − 1 + 1 = 2 1 5 2 3 3 6 1

Since cos 3 u = 4 cos 3 u − 3 cos u , we note that f ( 2 cos u ) = 2 cos 3 u , and hence f n ( 2 cos u ) = 2 cos ( 3 n u ) Differentiating this identity, we see that − 2 sin u ( f n ) ′ ( 2 cos u ) = − 2 sin ( 3 n u ) × 3 n The first identity shoes that f n ( 2 cos 3 n 2 k π ) = 2 k = 0 , 1 , 2 , . . . , 3 n − 1 while the second identity shows that ( f n ) ′ ( 2 cos 3 n 2 k π ) = 0 k = 1 , 2 , . . . , 3 n − 1 and we note that 2 cos 3 n 2 ( 3 n − k ) π = 2 cos 3 n 2 k π k = 1 , 2 , . . . , 2 1 ( 3 n − 1 ) Thus f n − 2 has the simple root 2 and the repeated roots 2 cos 3 n 2 k π for k = 1 , 2 , . . . , 2 1 ( 3 n − 1 ) . Since f n − 2 is a polynomial of degree 3 n and we have found 1 + 2 × 2 1 ( 3 n − 1 ) = 3 n roots, we have found them all. Thus there are 1 + 2 1 ( 3 n − 1 ) = 2 1 ( 3 n + 1 ) distinct zeros for f n − 2 . When n = 1 6 we get the answer 2 1 5 2 3 3 6 1 .

Similarly, g n ( 2 cos u ) = 2 cos ( 2 n u ) .