Faster Than Gravity

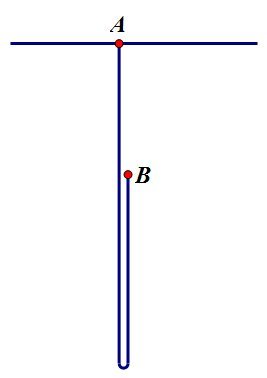

A heavy uniform chain has length

L

and mass

m

. The chain is inextensible and perfectly flexible. One end

A

of the chain is fixed to the ceiling. The other end,

B

, is held at rest right next to

A

at the level of the ceiling (so that initially

A

and

B

are at the same height).

A heavy uniform chain has length

L

and mass

m

. The chain is inextensible and perfectly flexible. One end

A

of the chain is fixed to the ceiling. The other end,

B

, is held at rest right next to

A

at the level of the ceiling (so that initially

A

and

B

are at the same height).

The second end

B

is released, and the chain starts to fall until the chain is fully extended with

B

vertically below

A

. Note that there are no internal friction forces operating within the chain, and so energy is conserved throughout the motion. The horizontal component of the motion of the chain can be ignored.

The second end

B

is released, and the chain starts to fall until the chain is fully extended with

B

vertically below

A

. Note that there are no internal friction forces operating within the chain, and so energy is conserved throughout the motion. The horizontal component of the motion of the chain can be ignored.

It can be shown that the time T that it takes for the chain to become fully extended is T = g 2 L D π Γ ( B A ) C where A , B , C , D are positive integers, with A , B coprime. Find the value of A + B + C + D .

N.B. The time T ≈ 0 . 8 4 7 g 2 L is less than the time g 2 L taken for a particle to fall a height of L from rest. The chain falls "faster than gravity".

The answer is 11.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

2 solutions

Oh wow. That was invigorating!

Log in to reply

yes it took me a whole day to think the crux of this problem and then solve it.

A more direct calculation of T involves the substitution x = cos 4 θ , giving T = 2 g L ∫ 0 2 1 π 1 + cos 2 θ cos 2 θ d θ = = = = 2 g L ∫ 1 0 1 + x 2 1 x 2 1 ( − 4 x 4 3 1 − x 2 1 1 ) d x 2 1 g L ∫ 0 1 x − 4 1 ( 1 − x ) − 2 1 d x = 2 1 g L B ( 4 3 , 2 1 ) g L 2 Γ ( 4 5 ) Γ ( 4 3 ) Γ ( 2 1 ) = 2 g L Γ ( 4 1 ) Γ ( 4 3 ) Γ ( 2 1 ) 2 g L π 2 Γ ( 4 3 ) 2 Γ ( 2 1 ) = g 2 L π Γ ( 4 3 ) 2

Thanks for posting this problem. I obsessed over this problem for a couple of days. One thing that bothers me and maybe you can help me understand it - is why can't I use the velocity of the center of mass of the system when calculating its kinetic energy. When calculating the potential energy using the center of mass of the whole system the result is the same as what you got by calculating the potential energy of the left-hand side and adding it to the potential energy of the right-hand side. When adding up kinetic energies, you assumed that the left-hand side is stationary. However, the left-hand side's center of mass is not stationary with respect to the fixed point A. In fact the velocity of the center of mass of the whole system can be obtained to be L/2(L-x)x'. Which would make the solution to be T=1/2*(2L/g)^1/2. Where did I go wrong?

Log in to reply

You cannot use the velocity of the centre of mass like you want to. For example, consider a system consisting of a planet orbiting a sun. If we ignore all other forces, there are no external forces acting, and so the centre of mass of the sun/ planet system does not accelerate. In many reasonable implementations of this model, we could say that the centre of mass was stationary. By your argument, the KE of the system would be constant, or even zero, which is not the case.

Alternatively, consider a rotating sphere. It's centre of mass is stationary, but it certainly has KE!

The problem is not just that considering only the motion of the centre of mass ignores rotational effects (which are not relevant in this case). Consider two identical particles, moving in opposite directions with the same speed, attached to each other by a light elastic string. The centre of mass of this system is stationary, but there is plenty of KE.

Ultimately, you calculate KE by regarding an object as a collection of particles, and add up ( by integration) the individual KE of those particles. In certain circumstances, we can obtain short-cut solutions. For example, the total KE of a rigid body is half the mass times the square of the speed of the centre of mass, plus a similar term allowing for the angular motion of the object about its centre of mass, involving the angular velocity and the inertia tensor.

Log in to reply

Sorry, but this has not addressed my issue. I understand that that the KE (as well as the PE) is relative depending on what your point of reference is. This is because the velocity is relative depending on your point of reference (and so is the height when you calculate the PE). In the case of the planetary system the KE of the whole system could indeed be considered zero if you are treating the whole planetary system as one system, and you are not concerned with individual parts However, in the folding chain problem, you chose to consider point A fixed, therefore all your calculations are with respect to that fixed point. When you considered the velocity of the left-hand side to be zero you arbitrarily chose to consider just the top of the chain as its speed. Why not consider the bottom part? In fact, when considering the velocity of a particle you should use its center of mass. Consider a chain being coiled up in a ball and thrown in some horizontal direction. When considering its kinetic energy, you would not use the velocity of an arbitrary link in your calculations of KE, would you? No, the chain could be flailing in all the different directions, but it's the center of mass of the chain that you would consider. this actually works in all the problems involving conservation of momentum, etc. This should've worked here.

Log in to reply

@Ilya Lyubarsky – Suppose that a system consists of n particles, and that the j th particle has mass m j and position vector r j . Then the centre of mass of the system has position vector R = M 1 j = 1 ∑ n m j r j where M = j = 1 ∑ n m j is the total mass of the system. Then it is true that M R ˙ = j = 1 ∑ n m j r ˙ j so that the momentum of the system is equal to the "momentum of the centre of mass", namely the total mass times the velocity of the centre of mass. The same is not true of kinetic energy, since 2 1 M ∣ ∣ R ˙ ∣ ∣ 2 = j = 1 ∑ n 2 1 m j ∣ r ˙ j ∣ 2 Check it out! The KE of the system is not equal to 2 1 M ∣ R ˙ ∣ 2 , which is what you are insisting upon.

No part of the string on the LHS of this problem is moving. The chain is inextensible, and so there is a fixed length of chain between any point on that chain and the end of the chain at A. If any part of the LHS was moving downwards, then the chain would be either stretching or breaking.

Look at this problem another way. Suppose that you have a tube of glue, and you are spreading the glue in a vertical line on a wall, starting at the top and working down. Suppose that the glue is so tacky that once it touches the wall, it sticks and does not move. As you move the applicator down the wall, the amount of glue on the wall increases, and so the centre of mass of the glue on the wall will move downwards. However, all the glue on the wall is stationary, so has no KE, regardless of what its centre of mass is doing.

To understand KE, we need more than the motion of the centre of mass. If the moving object is non-rigid, there will be internal motions (like in my example of two particles joined by a string). If the object is rigid, there will be rotational effects to consider. If we flung a balled-up chain which proceeded to unravel, determing the full details of its motion might well require studying its behaviour link-by-link. For that matter, the model of this problem has been analysed (and results compared with experiment) for a system of chains made up of links which do move a little horizontally as the RHS portion of the chain moves to the LHS.

Going back to planetary motion. If there were a frame in which the KE of the system was zero, there would be a point on the orbit where both sun and planet have the same velocity. That would mean that the planet was, at that moment, stationary relative to the sun, and this would mean that the planet's subsequent motion was to fall radially into the sun! In addition, unless the orbit is circular, GPE will change, and to the KE of the system will not be constant, whereas 2 1 M ∣ R ˙ ∣ 2 is constant.

Great blend of mechanics and calculus , sir by the way can you help me to find the tension at end A , when end B has fallen through a distance x below its initial level .

Log in to reply

To provide the necessary deceleration of the bottom part of the right-hand chain, the tension at the loop of the chain is 4 L m x ˙ 2 , so the tension at the end A is 4 L m x ˙ 2 + 2 L m g ( L + x ) .

In this model, the acceleration a , the speed x ˙ and the tension T A at A all tend to ∞ as x → L . This reflects the fact that the tip of the chain is, in some sense, being cracked like a whip.

If we substitute x = 2 L sin 2 2 θ then the integration turns to 0 ∫ π / 2 cos θ which would now be easy and it would avoid eliptic integrals.

Log in to reply

If you look at my own note, you will find my alternative substitution which evaluates the integral without elliptic integrals.

Log in to reply

Yes I saw, So this is the third substitution we could have used

It's a good problem. Could you please tell me how to make a GIF?

Log in to reply

I used Mathematica, which has the feature to export a time sequence of images as a GIF built-in.

Well I didn't really solve it because I recently read the same problem few days ago in "Inside Interesting Integrals" by Paul Nahin, but Yeah it surely was exhausting to solve though.

@Mark Hennings No Sir, the original paper by Calkin and March is available on the net too............ Here is the first part and here is the second part.........

This was so much fun! Huge respect to Mr. Hennings for posting such an amazing problem!

There is already a really nice solution written by Mr. Hennings, but I had a lot of fun solving this problem, and I want to "catalogue" my solution for future reference (in my own words), if that makes any sense!

Anyways, let's jump right in. We have to construct an expression that allows us to find the gravitational potential energy when the end of the string has fallen some given distance. When the right side of the string has shortened by some amount ℓ , this length is "transferred to the left side of the string system. Thus, the length of the right side at some time t is given by 2 L − ℓ ( t ) and the left side is 2 L + ℓ . We can then say that to find the gravitational potential at some instant in time, we can integrate over each point lying on the longer side the rope (the left side), multiply that number by 2 , to get the energy for both sides, then subtract the energy from 0 to 2 ℓ , in order to take out the missing component of the rope. Thus, we have:

d m = L m d L

U ( ℓ ) = 2 ∫ 0 2 L + ℓ − L x m g d x − ∫ 0 2 ℓ − L x m g d x = L 2 m g ℓ 2 − L m g ( 2 L + ℓ ) 2 = L m g ( ℓ 2 − L ℓ − 4 L 2 )

The kinetic energy is a whole other story. We must consider the fact that only the right side of the chain is moving

K ( ℓ ) = 2 1 L 2 L − ℓ v 2

Where the velocity is given with respect to how the distance between the top of the chain and the ceiling is changing in time, so 2 ℓ (I was a bit unclear on this , but it was the only way my solution wouldn't be off by a multiplicative factor of 2 ). Anyways, putting this together:

U 0 = U ( ℓ ) + K ( ℓ ) ⇒ − 4 m g L = L m g ( ℓ 2 − L ℓ − 4 L 2 ) + 2 1 L 2 L − ℓ v 2 ⇒ L g ℓ 2 − g ℓ + 2 L 2 L − ℓ v 2 = 0

v = 2 L 2 L − ℓ g ℓ − L g ℓ 2 = 2 L 2 L − ℓ g ℓ − L g ℓ 2

v 1 = 2 L 1 g ℓ − L g ℓ 2 2 L − ℓ

Now we integrate over v 1 to find the total time. Since v is a function of a = 2 ℓ , we have to do a change of variables:

T = ∫ 0 L v ( a ) 1 da ⇒ ℓ = 2 1 a ⇒ d ℓ = 2 1 d a

And so we get:

T = ∫ 0 2 L v ( ℓ ) 2 d ℓ = 2 ∫ 0 2 L 2 L 1 g ℓ − L g ℓ 2 2 L − ℓ d ℓ

Now, we will do another change of variables. Let ω = L 2 ℓ . We now have:

T = 2 g L ∫ 0 1 2 L ω − 4 L ω 2 2 L − 2 L ω d ω = 2 g L ∫ 0 1 ω − 2 1 ω 2 1 − ω d ω = g L ∫ 0 1 2 ω − ω 2 1 − ω d ω

⇒ g L ∫ 0 1 ω − 1 / 2 ( 1 − ω ) 1 / 2 ( 2 − ω ) − 1 / 2 d ω

This integral looked VERY similar to the Beta function, but I couldn't exactly figure out how to express it in terms of the Beta (or Beta's) so I used Wolfram Alpha to simplify. It gave me:

⇒ g L ∫ 0 1 ω − 1 / 2 ( 1 − ω ) 1 / 2 ( 2 − ω ) − 1 / 2 d ω = g L Γ ( 4 1 ) 2 π Γ ( 4 3 )

By the Legendere Duplication Formula:

Γ ( 4 1 ) = Γ ( 4 3 ) π 2 ⇒ T = g 2 L π Γ ( 4 3 ) 2

And then we have:

A + B + C + D = 3 + 4 + 2 + 2 = 1 1

The standard model (developed by Cayley many years ago and much reproduced in textbooks) for this problem has the right-hand section of the chain falling freely under gravity, with no tension in that section of the chain. The bottom portion of that right-hand section is successively brought to rest by an inelastic collision (being prevented from falling further through being attached to the stationary left-hand section of the chain). This model is not energy-conserving. Recent experiments have shown that an energy-conserving model is the correct one. In the energy-conserving model, tension is continuous in the chain, and particularly so between the left-hand and the right-hand sections. The tension that exists in the left-hand section of the chain to bring successive portions of the right-hand section of the chain to rest then acts downwards on the right-hand section of the chain, giving the right-hand section an acceleration greater than that of gravity. These clips give a practical demonstration of this effect.

This paper by Wong and Yasui summarises the results. Unfortunately, the original 1989 paper on this topic, by Calkin and March, is only available online on payment of ready money.

At the moment when B is a distance x below the ceiling, the left-hand segment of chain has length 2 1 ( L + x ) , and hence has mass 2 L L + x m , and its centre of mass is a distance 4 1 ( L + x ) below the ceiling. On the other hand, the right-hand segment of chain has length 2 1 ( L − x ) , and hence has mass 2 L L − x m , and its centre of mass is a distance x + 4 1 ( L − x ) = 4 1 ( L + 3 x ) below the ceiling. Thus the gravitational potential energy of the system is − 2 L L + x m g × 4 1 ( L + x ) − 2 L L − x m g × 4 1 ( L + 3 x ) = − 4 L m g ( L 2 + 2 L x − x 2 ) The left-hand segment of the chain is stationary, while the right-hand segment of chain has speed x ˙ , and so the kinetic energy of the system is 2 1 2 L L − x m x ˙ 2 = 4 L m ( L − x ) x ˙ 2 Conservation of energy tells us that 4 L m ( L − x ) x ˙ 2 − 4 L m g ( L 2 + 2 L x − x 2 ) = − 4 1 m g L (since, initially, x = x ˙ = 0 ), and hence ( L − x ) x ˙ 2 x ˙ = = g x ( 2 L − x ) L − x g x ( 2 L − x ) Thus the time for the chain to fall is (substituting x = L sin 2 θ ): T = = = = ∫ 0 L g x ( 2 L − x ) L − x d x = g L ∫ 0 2 1 π 2 − sin 2 θ sin θ cos θ × 2 sin θ cos θ d θ 2 g L ∫ 0 2 1 π 1 + cos 2 θ cos 2 θ d θ 2 g L [ 2 E ( 2 1 ) − 2 1 K ( 2 1 ) ] g 2 L [ 2 E ( 2 1 ) − K ( 2 1 ) ] where K and E are the complete elliptic integrals of the first and second kinds respectively: K ( k ) = ∫ 0 2 1 π 1 − k 2 sin 2 θ 1 d θ E ( k ) = ∫ 0 2 1 π 1 − k 2 sin 2 θ d θ (see Gradshteyn and Rhyzik for this last evaluation). But since K ( 2 1 ) = Γ ( − 4 1 ) 2 8 π 2 3 , E ( 2 1 ) = Γ ( − 4 1 ) 2 4 π 2 3 + 2 π Γ ( 4 3 ) 2 we deduce that T = g 2 L π Γ ( 4 3 ) 2 making the answer 3 + 4 + 2 + 2 = 1 1 .