Figure 8's In A Plane

The number of "Figure 8's" that you can draw in a plane such that they do not cross each other is...

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

7 solutions

Is there a proper definition for 'countable infinite'. Because if it is countable, how can it be infinite? Isn't it the definition of infinite. Cannot be counted or measured?

Log in to reply

Countably Infinite sets are sets for which there exists a bijection with the set of natural numbers, i.e. a set A is countably infinite if each of its elements can be mapped to a unique element (one-to-one correspondence) in the set of Natural Numbers.

As an example, consider the number line extending infinitely in the positive direction. Each integer number represents a number that can be described by a function X = positive integer. This function has infinite values, but, is countable in terms of the function. This is countably finite. On the contrary, consider the portion of the number line between X = 1 and 2. Though this is a small segment of the infinite number line, yet, it can have infinite number of points inside it unless we bind it by a finite relationship that identifies specific points only in that segment. This unrestricted portion between X =1 and 2 is uncountably infinite.

Log in to reply

will u please clearify it more so that i could understand all the 4 terms countable finite,uncountable finite ,countable infinite and uncountable infinite..??

Log in to reply

@मनोज पाटीदार – And this is why mathematicians say math is so inconsistent. People define these things differently. I just went by the symbols for this since those are usually more consistent lol. For this I'm going to go with the way wikipedia defines these terms since I'm guessing those are the most popular ways of defining these terms.

Countable set : Can be put into bijection with some subset of the natural numbers. Can be finite or infinite. Countable finite : Proper subset of natural numbers (i.e. not all of them). Same as finite set. Countable infinite : Bijection with the entire set of natural numbers.

Uncountable set : Cannot be put into bijection with natural numbers.

The term uncountable finite is not well-defined. In math you can't just put words together and ask what they mean. You have to define the new word and it doesn't make sense to talk about finite/infinite uncountable sets. By definition uncountable sets are infinite.

Basically sets can have 3 sizes. Finite, countable infinite, and uncountable. Countable infinite just means you can map each element in the set to one of the natural numbers (technically there's exactly one natural number for each element in the set, not more, not less). Uncountable sets are /defined/ as having a size (cardinality is the technical math term for size of a set) larger than countable infinite (the weird N_0 from the problem). Since we've defined uncountable infinite to just be anything larger than countable infinite, no sets can have a size larger than that. Even if you take the size of the real numbers as the "basline" size of a uncountable set (remember they'll all have the same size so you can use any uncountable set) no one, at least as far I know, has found a set with a larger cardinality, so for at least our current level of math, we don't need any other definitions.

I imagined nesting the 8's, "two" inside of each one. Which I thought would give us 2 ℵ 0 = ℵ 1 (Really, imagine the 8's sideways, so they are ∞ signs.) But the center cross of each ∞ is a string of only finitely many 1's and 0's (lefts and rights). Foolish. Clearly countable for several reasons.

Log in to reply

Actually, two-to-the-aleph-null is just beth one. That it is also aleph one is Cantor's Continuum Hypothesis, which was never proved or accepted.

The interiors are not disjoint because you can draw an eight inside the loop of another eight. They are not crossing each other.

Log in to reply

When the answer says "two loops with disjoint interiors", it is talking about the two loops of a single figure eight.

what about number of circles you can draw then it should also be the same then,if iam wrong please correct me

Log in to reply

For circles we could try to form the same argument by choosing one or more rational points inside each circle. But notice that it is entirely possible for two different circles to share the same choice of point or points, so there is no proof of injectivity.

If you look at the diamond-shaped space between two 8's, you could draw a smaller 8 inside that, which would then make two smaller diamonds that you could put smaller 8's inside of, etc. So there's one of these infinite fractal series of 8's for each of the countably infinite diamonds on the original grid, so how can it still be countable?

Log in to reply

The same way the rational numbers can be counted. You start with the ones whose numerator and denominator, in lowest terms, add up to one. Then 2, then 3, and so on.

Countable, enumerable and even computable can be ways in logic to think of the elements of a set, such as {1,2,3, ....,10}. Now continue that set without end and you have an infinite countable set.

Now a set of all the real numbers between zero and one is infinite, and theres no way systematically list all the elements of that set, because there must always be an infinite number of elements between any element and any candidate next element.

This helps with the intuition that it is NOT POSSIBLE to systematically list through all the elements of an infinite set of infinite sets.

As the set of rational numbers IS enumerable/countable, that is, there is a systematic way to work through all the possible ratios from all the possible combinations of two infinite sets of integers, and yet there is no way to enumerate even a single set of all the real numbers between any two real numbers SO...

- Set of real numbers is not countable

- Set of rational numbers IS countable

- As real numbers are made up of rational and irrational, it MUST be the irrational part of the real numbers that is NOT countable.

THAT should give you a feel for irrational being a bigger set, that and the fact that between any two rational numbers on the number line, there must be an infinite number of irrational numbers

Have you considered the possibility that given any 8 1 we can draw another 8 2 inside the top loop of 8 1 whose top loop loop is arbitrary close to the top loop of 8 1. Why will this not say that there are at least uncountable 8's?

Log in to reply

So far you have described exactly two figure 8s, which is quite far from an uncountable number. At best you are describing an inductive process, where given one figure 8 you can always add one more. Such a process produces only countably many 8s. Where do you describe any set of uncountable size?

A figure 8 is noting more than a twisted linear interval. Since a linear interval must contain both rational and irrational numbers, so too must a figure 8. Since there are only countably infinitely many rationals, the upper bound to this problem is clearly countable infinity.

Next make all figure 8's vertical and have their crossing points be on the x-axis. Let the greatest width of the first figure 8 be 1. Skip (1/4) on the x-axis and let the second figure 8 have a greatest width of (1./4). The width used up thus far is 1 + (1/4) + (1/4) = 1 + (1/2). For the third figured 8 skip (1/8) and make the next figure 8 have a width of (1/8). We have now used ((1) + (1/2) + (1/4)). There are infinitely many figure 8s and they never reach 2 on the x-axis.

So the lower bound is some infinity. Since the upper bound is countable infinity, the lower bound is also countable infinity. Hence the answer is countable infinity. <------ Answer

Log in to reply

Your first paragraph is wrong. What does it mean for a figure eight to contain a number? There aren't any numbers in the plane, there are only points. And it is not true that every curve in the plane contains a rational point. Consider, for example, the line x= π .

Also, your reasoning, if it were valid, would also apply to circles. But we can draw uncountably many non-overlapping circles in the plane: simply make a circle centered at 0 with radius r for every r>0.

And in your second paragraph you have the whole plane, so why not just, for each integer n, draw an arbitrary figure eight in the region between x=n and x=n+1.

You need that rational points are dense in the plane, and that the interior of the loops contain a section of plane

If you tile a collection of points in R there are uncountably infinite amount of points in between the objects. This allows for an uncountable number of figure eights in between each figure eight.

Log in to reply

Certainly cardinality arguments allow for uncountably many figure eights, but the onus is on you to prove the existence of such a configuration. Do you have any construction to justify your claim?

Log in to reply

The cardinality of an interval of R is the contiuum

Log in to reply

@A Former Brilliant Member – That is common knowledge. What does this have to do with producing uncountably many disjoint figure eights?

You can easily make a figure eight for each point of those uncountably many, but how do you make it so they don't overlap? (You can't)

It seems to me that the problem should state the figure 8s are all the same size? If they are of different sizes an infinite number of figure 8s can fit in any of the holes in the above diagram, and in an infinite number of arrangements in each hole, and they are clearly uncountable then.

No they are not. Because they are unable to cross eachother, the number of them is countably finite. Check the answer by Erick Wong for more detail.

Consider any tiling of 8s, since Q 2 is dense in R 2 we can pick a q and r in each of the circles that make up the 8. Two different 8s will be equal if and only if they are made up from the same circles, so different circles will have different a ( q , r ) assigned. Consider the set A = { ( q , r ) ∈ Q 2 × Q 2 , ( q , r ) is assigned to an 8 of the tiling } ⊂ Q 2 × Q 2 There´s a bijection between the set A and the set of 8´s in the tiling. Since Q 2 × Q 2 is countable infinite we have that A is at most countable infinite. Finding a countably infinite tiling is rather easy so the proof concludes. (Someone else already gave this answer but this one has more symbols :) )

Me encanta lo que de que su respuesta tiene más símbolos. :-D Además, son contables, aunque no sean infinitos. ;-)

Uncountably infinite. You can make smaller 8's inside the both loops of each 8 and then even smaller 8's inside the loops of the smaller 8's and even even smaller ones inside the loops inside the loops inside the loops of the biggest 8 and so on

But however small you make your loops, they will always have an area greater than zero and therefore there will always be at least one (technically an infinite amount) of rationals within every loop. I can then assign every rational to the loop which that rational is inside it, this forms a surjection from Q 2 to every loop. This means that the amount of loops are less than or equal to the amount of rationals, since the amount of loops are infinite and the rationals are countably infinite (the smallest infinite), this means that the amount of loops are countably infinite.

Edit: When I say rationals, I mean the tuple (p,q), where p and q are rationals

I think the 8s have to be of a fixed size.

Given a non intersecting collection of figure 8s, associate each figure 8 with two rational points (points with rational x and y coordinates), one from each loop. Then this mapping is injective. Since QxQ is countable, so is the collection of figure 8s.

There is no mention about size of figure. Hence answer is uncountably infinite. I can draw many eights inside one of the eights already drawn and so on.. What do you think Daniel and Tong?

Log in to reply

However, the figure 8's cannot intersect. Even if you put some figure 8 inside another one, it would still be countably infinite.

To check your understanding of what is ℵ 0 and what is ℶ 1 here is an example: ℵ 0 is the cardinality of rational numbers, and ℶ 1 is the cardinality of the real numbers.

An example of a figure that can be put in the plane an uncountably infinite number of ways ( ℶ 1 ) is the circle; you can center all of them at ( 0 , 0 ) and let their radii be all the real numbers; this would be uncountably infinite.

Log in to reply

Nesting figure eights inside of each other allows for an uncountable infinity of them. Consider a fractal nesting of figure eights, it is entirely possible to form a structure for which a one to one correspondence is impossible to form from the natural numbers. Consider a set of 10 figure eights within each loop of the figure eights, and 10 within that, etc... you can quickly form an isomorphism to infinite decimals as a way of describing the location of a nested loop. Proceed with a cantor diagonalization argument and it's clear that the number of figure eights is not countable. If you had stated that the loops must remain the same size, I would agree that you would only have a countable infinity, but you did not specify this.

Thanks for the reply Daniel. I would like to know how to count all those figures of 8 inside each other using natural numbers. For example, we know how to count rational numbers using natural numbers. How to do the same using for these figures?

Log in to reply

@Snehal Shekatkar – If you know that Rational numbers are countable, then so are any finite product of rational numbers: Q × Q × Q . . . × Q . So pick a rational point from each loop of the figure 8, then the collection of figure 8s can be mapped injectively into the set of Q 2 × Q 2 , which is countable.

Yes, you can do that, but by my mapping into Q 2 × Q 2 , these two figure 8 would be mapped into different elements. The key here is that the mapping is injective.

Log in to reply

Please elaborate

Log in to reply

@Snehal Shekatkar – Rational Numbers are countable since rational numbers are of the form $\dfrac{m}{n}$, where $m$, $n$ are integers.

I think the words "that you can draw" eliminates your scenario. Maybe not, as one cannot draw an infinite amount of anything.

Can you elaborate on what you mean by "the mapping is injective"?

Why doesn't this proof work for "circles in a plane"?

I visualized the answer to this question by imagining that the infinite plane somehow has X coordinates that run from one to infinity , and Y coordinates that run from one to infinity .

I then remembered how we demonstrated that this set of rational numbers (integer fractions) is countably infinite. We imagined each fraction being a point in an infinite "quadrant one" of our coordinate system, the X coordinates going from one to infinity, the Y coordinates going from one to infinity. When we moved through every possible rational number in a diagonal pattern , starting with one over one, continuing with the next diagonal one over two, two over one, continuing with the next diagonal one over three, two over two, three over one, etc., we are able to create a one to one match between the set of rational numbers and the set of positive integers.

It is then easy to imagine that each of these "figure rights" is one of these fractions, the numerator inside the left circle, the denominator inside the right circle . If the rational numbers are countably infinite, then this infinite pattern of figure eights is countably infinite .

The only flaw in this imagined proof is the fact that we do not account for the fact that the infinite plane is theoretically four times larger than the plane of only the positive X and Y coordinates as described above. However this is easy to circumvent. We can imagine that the numbers in our infinite plane start at one at the axis , with all the numbers starting at the axis and going to the right , and all the even numbers starting just to the left of the axis and moving to the left. In this way, we can demonstrate that the infinite plane is equal in size weather we start at the origin and only move toward infinity into directions , or if we go to infinity in all four directions.

This may not be as elegant away to prove the point as some of the other answers , but it works for me.

I can't see how the numbers in an infinite grid can start at one corner, an infinite grid isn't supposed to have corners or edges. How is the coordinate system without negative values the same size as the set of points of an infinite grid.

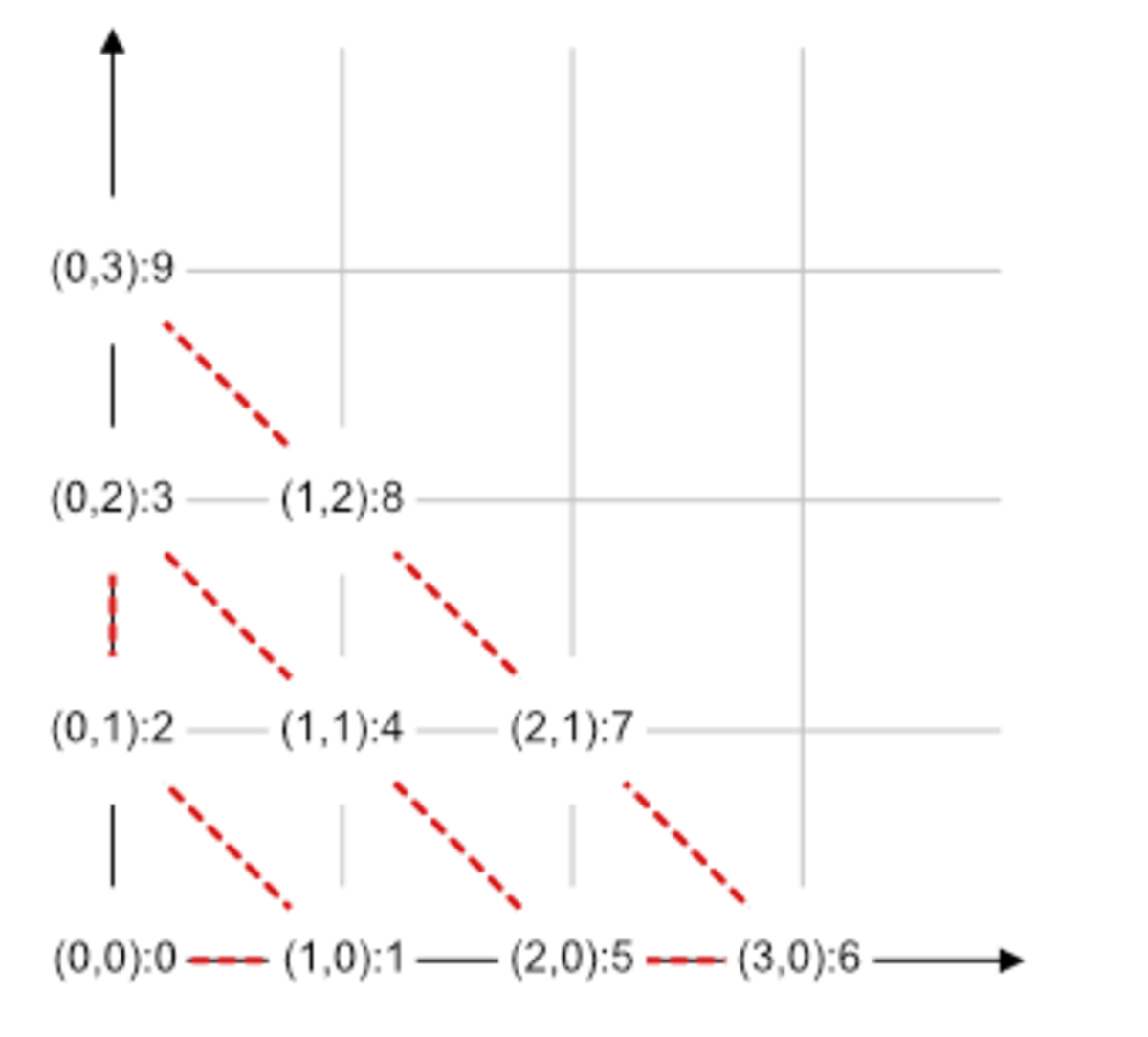

Ome can map each integer coordinates to a 8. These coordinates can be mapped to integers. Start in a corner, move 1 right (x+1,y) then along the diagonal (x-1,y+1). When you hit X=0 move one up (x,y+1) then along the diagonal (x+1,y-1). When you hit Y=0 repeat the process.

You will end up with a trail covering the whole plane! Each coordinate would have also a number.

Here are the first mappings:

( 0 , 0 ) ( 1 , 0 ) ( 0 , 1 ) ( 0 , 2 ) ( 1 , 1 ) ( 2 , 0 ) ( 3 , 0 ) ( 2 , 1 ) ( 1 , 2 ) ( 0 , 3 ) ↦ ↦ ↦ ↦ ↦ ↦ ↦ ↦ ↦ ↦ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Etc !

what about when either of the coordinates is negative? You can't draw a single line connecting all points. In your representation the ''infinite'' plane has two edges.

Log in to reply

You can fold the infinite plane at the two axes and get two edges. In terms of mapping the integer coordinates, you can map the coordinates (x,y) in each quadrant to (4|x|-q, 4|y|-q) where q is 0 for 1st quadrant, 1 for 2nd and so on.

Clearly the number is at least countably infinite, just by tiling translated copies of a single figure 8. Conversely, suppose we have a set of figure 8s drawn in the plane with no crossings. Each such figure 8 consists of two loops with disjoint interiors: we associate to each figure an arbitrary fixed pair of points, one point in the (open) interior of each loop, in some arbitrary order. By the density of rationals, we may furthermore choose the points in such a way that they have rational Cartesian coordinates.

Now suppose two figures A and B share the same first point x: then A and B each have exactly one loop enclosing x. Since these loops don't cross, one must be contained in the interior of the other; WLOG say B's x-loop is contained within A's x-loop. Then figure B must be entirely contained within A's x-loop to avoid crossing, so that the second point of B is inside A's x-loop; the second point of A is outside of A's x-loop, so it cannot be equal to that of B.

We conclude that no two figure 8s can share both points, so they are less numerous than the set of point pairs of rational coordinates, which is Q 4 and thus countable.