Atoms....

You are given a new unknown element of atomic weight 124 (For time being, assume that this element has not been discovered) and you wish to find out the radius of the nucleus of the atoms present in it. You do the following steps:

You are given a new unknown element of atomic weight 124 (For time being, assume that this element has not been discovered) and you wish to find out the radius of the nucleus of the atoms present in it. You do the following steps:

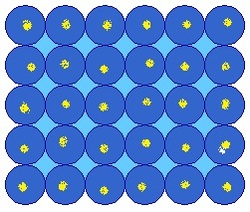

Step 1 : You carefully cut out a cm by cm mono-layer of atoms from it, and weigh it accurately and precisely to get nano grams. You can safely assume that the mono-layer looks similar to the figure above.

Note that this is not the actual mono-layer you have, but its lattice is similar to the above showed picture. We also assume that the atoms are spherical. The yellow dots represent the nuclei of the atoms.

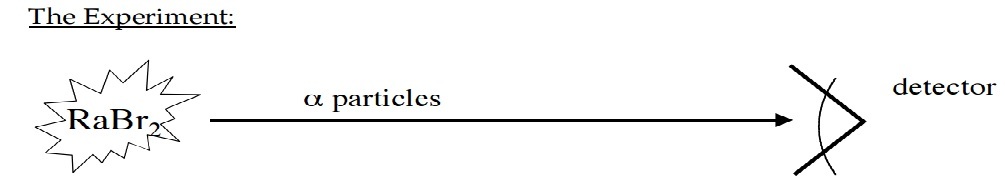

Step 2 : You put aside the mono-layer, and take a sample of radioactive radium bromide, which emits radiation. With the help of a Geiger counter ( or simply, a Detector ), you measure the count rate of this beam of particles to be hits min . The setup is something like this :

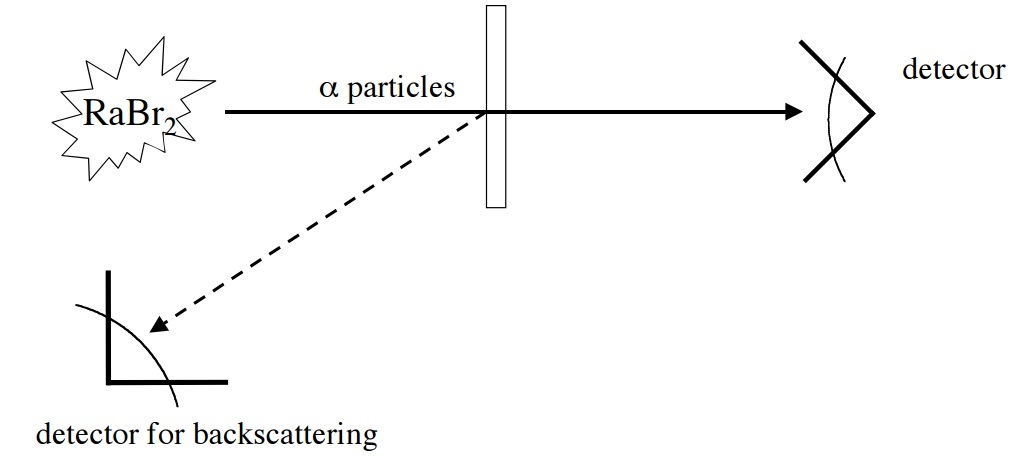

Step 3 : Without further delay, you subject the mono-layer you have with the same radiation uniformly throughout its surface. You also place a Geiger counter beside the emitter to measure the count rate of rebounded particles, which you found out to be hits min . The setup is something like this:

Now, given this information, you calculate the radius of nuclei of the atoms in the mono-layer to be some metres, where . Enter as your answer.

Details and Assumptions

-

Avogadro Number is taken as .

-

Pi is taken as .

-

particles are assumed to be point sized, when compared to large sized atoms in the mono-layer.

-

Step 2 and Step 3 are performed for the same amount of time.

This problem is original, and is inspired from MIT 5.111 Principles of Chemical Science Lecture-2, where the students perform an in-class imitation of the scattering experiment and calculate the radius of the "ping-pong ball" nuclei.

Since this problem is very different from conventional ones, people are invited to take part in discussions, and also suitable corrections will be made, if necessary.

The answer is -11.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

Let the radius of the nuclei (in meters) be r . To find r , we do the following calculations :

Step 1 : Number of atoms in the mono-layer( n ) = Gram Atomic Weight Weight in grams × N A = 1 2 4 6 × 1 0 − 1 0 × 6 . 0 2 3 × 1 0 2 3 = 2 . 9 1 4 3 5 × 1 0 1 2 .

Step 2 :

Probability of back-scattering = Total number of hits Number of Rebounds = Hit count rate Rebound count rate = 1 3 2 0 0 0 2 .

Since the particles rebound when and only when they hit one of the nuclei, we can compute this probability in another way :

Probability of back-scattering = Total area of the mono-layer Area occupied by the nuclei

= Area of the mono-layer ( π r 2 ) × n

= 7 × 9 × 1 0 − 4 2 2 × r 2 × 2 . 9 1 4 3 5 × 1 0 1 2 .

Step 3 :

Now, we equate the final answers of both ways in which we computed the same probability :

7 × 9 × 1 0 − 4 2 2 × r 2 × 2 . 9 1 4 3 5 × 1 0 1 2 = 1 3 2 0 0 0 2 ⇒ r = 3 . 8 5 8 4 7 5 5 . . . × 1 0 − 1 1 m .

Hence, the required answer is ( − 1 1 ) .