Inspired by Sharky Kesa

Let a , b , and c be real numbers such that

{ a + b + c = 1 2 3 . 4 5 6 a b + b c + c a = 3 8 1 0 . 3 4 5 9 8 4

Find the sum of the maximum and minimum values of c . Write your answer to 5 decimal places.

Bonus: Can you generalize it?

The answer is 82.30400.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

7 solutions

Good solution!

solving for c

c

=

1

2

3

.

4

5

6

−

a

−

b

→

a

b

+

(

1

2

3

.

4

5

6

−

a

−

b

)

(

a

+

b

)

=

3

8

1

0

.

3

4

5

9

8

4

we differentiate the second equation w.r.t b and put a'=0:

a

′

b

+

a

+

(

1

2

3

.

4

5

6

−

a

−

b

)

(

a

′

+

1

)

+

(

−

a

′

−

1

)

(

a

+

b

)

=

0

→

a

+

2

b

=

1

2

3

.

4

5

6

now we have a system of equation solving we get the pairs

(

a

,

b

,

c

)

=

(

8

0

.

3

0

4

,

2

0

.

5

7

6

,

2

0

.

5

7

6

)

,

(

0

,

6

1

.

7

2

8

,

6

1

.

7

2

8

)

.since the max,min of a is the same as for c,

m

a

x

(

c

)

+

m

i

n

(

c

)

=

8

0

.

3

0

4

+

0

=

8

0

.

3

0

4

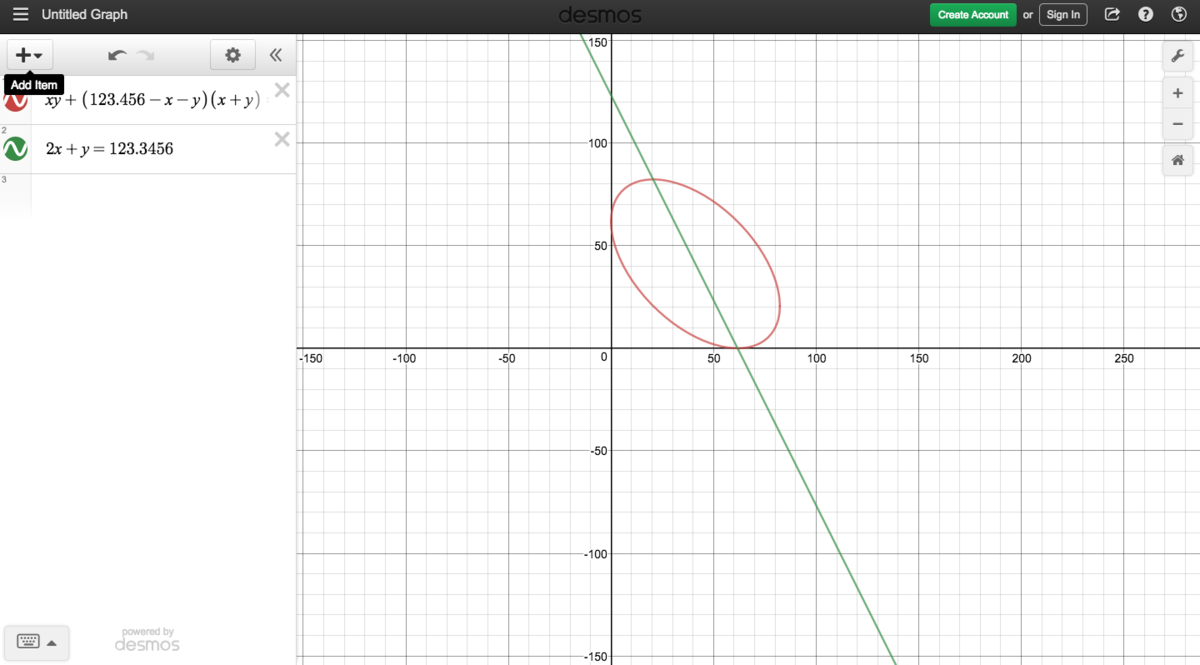

a visualization of the solutions:(the graph can show each of the solution is a min and max without having to take 2nd deravative)

Good solution!

Let x = 1 2 3 . 4 5 6 , y = 3 8 1 0 . 3 4 5 9 8 4 . Then we can find a 2 + b 2 + c 2 + 2 y = x 2 a 2 + b 2 + c 2 = x 2 − 2 y a 2 + b 2 = x 2 − 2 y − c 2 . . . . 1 a + b = x − c . . . . 2

Then by using QM - AM inequalities : 2 a 2 + b 2 ≥ 2 a + b Substitute the first and the second equation then squaring both sides we get : 2 x 2 − 2 y − c 2 ≥ 4 x 2 + c 2 − 2 x c then solving it we get : 0 ≥ 3 c 2 − 2 x c + ( 4 y − x 2 ) Two of these quadratic equation roots will be the minimum and the maximum value by solving the inequalities. So we just need to find the sum of the roots of this quadratic equation, by using vieta the sum of the root is : 3 2 x = 3 2 × 1 2 3 . 4 5 6 = 8 2 . 3 0 4

[Here's the generalization. Don't ask why it's lengthy, as I'm not a good solution writer.]

Let k > 2 be a positive real so that a + b + c = k and a b + b c + c a = ( 2 k ) 2 .

= > a 2 + b 2 + c 2 = 4 4 k 2 − 2 k 2 = 2 k 2 = 2 ( a b + b c + c a ) .

To find the minimum value of c , assume that a ≥ b ≥ c . It's obvious here that b = c = 0 isn't possible.

Assume that 0 ≥ b ≥ c .

= > b + c < k , b c ≥ 2 k 2 (impossible)

Assume that b ≥ 0 ≥ c .

= > a + b = k − c , a 2 + b 2 = 2 k 2 − c 2

= > 2 ( 2 k 2 − c 2 ) ≥ ( k − c ) 2

= > c ( 2 k − 3 c ) ≥ 0 .

Observe that k > 0 , c ≤ 0 = > 2 k − 3 c > 0 = > c = 0 .

As c < 0 isn't possible, m i n ( c ) = 0 .

To find the maximum value of c , assume that c ≥ b ≥ a > 0 .

We have a 2 + b 2 + c 2 = 2 ( a b + b c + c a )

= > ( a + b + c ) ( c + b − a ) ( c − b + a ) ( c − b − a ) = 0

It's obvious that a + b + c > 0 . Also, c + b > a + 0 and a + c > b + 0 .

= > c = b + a

= > c = a + b + 2 a b .

Substitute this into the first equation, we have a + b + a b = 2 k

= > c = a b + 2 k .

As we are looking for m a x ( c ) , we need to find m a x ( a b ) .

We have b + a ≥ 2 a b

= > 4 a + 4 b + 4 a b ≥ 3 b + 3 c + 6 a b

= > 2 k ≥ 3 b + 3 c + 6 a b ≥ 1 2 a b

= > a b ≤ 6 k

= > c ≤ 3 2 k .

Minimum value of c can be achieved when b = a = 2 k , c = 0 , while maximum value of c can be achieved when c = 3 2 k , a = b = 6 k .

Edit: k > 2 may not be true. I am, still, not yet sure if I can write instead that k > 0 .

this is a nice solution that goes through all the cases!(+1). i would suggest using the brackets[ like those, it makes equations in a different line easier to read.

Remember that when we want to show something is a maximum (or minimum), we have to

- Show that it is an upper bound.

- Show that the upper bound can be achieved.

You have done the first step, but not the second step. For example, even though x 2 + ( x + 1 ) 2 ≥ 0 + 0 , we have only show that 0 is a lower bound. It is not the minimum because it cannot be achieved.

@Aareyan Manzoor What do you think? Any mistakes?

If a + b + c = 3 k and a b + a c + b c = 3 d for some fixed k , d , and ( a 0 , b 0 , c 0 ) is a solution, then ( 2 k − a 0 , 2 k − b 0 , 2 k − c 0 ) is also a solution (plug it in). Thus if the minimum value of c is c m , the maximum value of c must be 2 k − c m , and their sum is 2 k . Plugging 3 k = 1 2 3 . 4 5 6 gives 2 k = 8 2 . 3 0 4 .

Of course, this requires us to first show that there exists such solution, and the maximum and minimum of c exist. But once you get both of these, the rest follows immediately.

To show these two, note that a , b , c are the roots of x 3 − 3 k x 2 + 3 d x − e = 0 for some real e . Its derivative is 3 x 2 − 6 k x + 3 d . If this is always positive, then it always has only one root for any e , so there doesn't exist such solution. Thus first we must show that 3 x 2 − 6 k x + 3 d can be non-positive; this can be proven by simply checking that the determinant 3 6 ( k 2 − d ) is non-negative. That is, if d ≤ k 2 , we will have a solution.

Now, it's easy to see that if e is very big or very small, then there is only one root. So there's a bounded interval I where e must be in this interval in order for the equation to have three roots. And since e is bounded, there is also a bounded interval J in which if x ∈ J then x 3 − 3 k 2 + 3 d x ∈ I , which means no e will give this root, which means x is not part of a solution. So a , b , c ∈ J , showing bounded-ness.

Good solution!

For the general case, we assume a + b + c = p a b + b c + c a = q Now, b = p − c − a . So, a ( p − c − a ) + ( p − c − a ) c + c a = q ⟹ a p − c a − a 2 + c p − c 2 − c a + c a = q ⟹ a 2 + a ( c − p ) + ( c 2 − c p + q ) = 0 If we want a to have a real value, we need to impose the following condition. ( c − p ) 2 − 4 ( c 2 − c p + q ) ≥ 0 We may want to use the completing square technique here. After that, we'd get ( 3 c − p ) 2 ≤ 4 p 2 − 1 2 q ⟹ − 4 p 2 − 1 2 q ≤ 3 c − p ≤ 4 p 2 − 1 2 q ⟹ 3 p − 3 2 p 2 − 3 q ≤ c ≤ 3 p + 3 2 p 2 − 3 q Hence, the upper and the lower bounds represent the maximum and minimum values for c . [These two values can then be used to get the corresponding real values of a and b . Also, for the upper and lower bounds of c to be real, we need to impose the condition: p 2 ≥ 3 q .]

Therefore, the sum of max and min values of c is 3 2 p For this particular problem, we have p 2 > 3 q . So, the answer is 3 2 × 1 2 3 . 4 5 6 = 8 2 . 3 0 4

Good solution! Same method :)

Log in to reply

I don't see much similarity between our solutions. Moreover, you didn't address the general case.

Log in to reply

I did. I mean I thought of this problem using this method, but then I found out the general case.

Edit: I did address!

Log in to reply

@Steven Jim – a + b + c = k and a b + b c + c a = 4 k 2 is not general enough. Your arguments then start with a 2 + b 2 + c 2 = 2 ( a b + b c + c a ) which is again not the general case.

Log in to reply

@Atomsky Jahid – It is. Maybe I did not really address it well, but remember that p 2 ≥ 3 q isn't that straight.

Log in to reply

- I didn't think our solutions share much similarity. That's why I replied, "I don't see much similarity between our solutions" to your comment which said, "Same method :)".

Then I said, "you didn't address the general case". It's because you assumed a + b + c = k and a b + b c + c a = 4 k 2 which is not apparent from the given data. You are the problem setter here and you didn't really clarify it. Stating that a b + b c + c a = 4 1 2 3 . 4 5 6 2 would have been a better option if you wanted everyone to solve it that way.

To a commoner (like me), 1 2 3 . 4 5 6 and 3 8 0 1 . 3 4 5 9 8 4 would seem like two unrelated numbers. In that perspective the general case means setting two different values for the expressions a + b + c and a b + b c + c a . If you clarified that the values you assigned are related in some way, then your way would have addressed the general case. Other than that, it addresses a specific case. [Mark's solution also incorporates that assumption.]

Just because I said " a + b + c = k and a b + b c + c a = 4 k 2 is not general enough" doesn't mean you have to lose your sleep over that. I simply stated what I thought. Also, I've backed my statements with rationale. There's no overreaction in between.

@Atomsky Jahid – Anyways, read Mark's solution. You'll see why I generalized my problem that way.

@Atomsky Jahid – If you want to say someone's solution is not generalized, you have to look his/her way. I generalized it in a different way (which, I know, is not really complete), but I did think of setting 2 different values (stuck afterwards). Your way is really good (seriously) if you want to solve a (more) general problem. But considering this problem only, then my way is somewhat generalized.

There's nothing to argue here. I generalized this problem from my perspective, while you do so from yours. And since everyone's perspectives are different, we shouldn't say stuff like "Your way isn't general (imo)".

Don't overreact anyways. It's just a solution. No one cares about the difference if both are generalizations and both seems true, they are just going to find whatever way looks better to them.

The generalization can be found out by simply squaring the first equation, and then using Titu's lemma.....

If a + b + c = k > 0 and a b + a c + b c = 4 1 k 2 , then a , b , c are the real roots of the cubic equation f ( X ) = X 3 − k X 2 + 4 1 k 2 X − q = 0 for some real q . Now f ′ ( X ) = 3 X 2 − 2 k X + 4 1 k 2 = ( X − 2 1 k ) ( 3 X − 2 1 k ) and so f has turning points at 6 1 k and 2 1 k . Since f ( 6 1 k ) = 5 4 k 3 − q and f ( 2 1 k ) = − q , we deduce that 0 ≤ q ≤ 5 4 1 k 3 .

When q = 0 , the roots of f ( X ) = 0 are 2 1 k , 2 1 k , 0 and so the least possible value of c is 0 .

When q = 5 4 1 k 3 , the roots of f ( X ) = 0 are 6 1 k , 6 1 k , 3 2 k , and so the largest possible value of c is 3 2 k . This makes the answer in this case equal to 8 2 . 3 0 4 .

If k < 0 , then the largest value of c is 0 and the least value of c is 3 2 k , and so the sum of the smallest and largest values of c is still 3 2 k .