Commemorating the October Revolution!

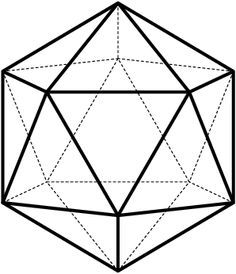

Comrade Markov (Андрей Андреевич Марков, 1856-1922) stands at a vertex,

A

, of an icosahedron. After every minute, he travels to one of the five adjacent vertices, along an edge, with equal probability. After 31 hours and 57 minutes (having traveled exactly 1917 times), is he more likely to be back at point

A

or at the opposite point

B

of the icosahedron?

Comrade Markov (Андрей Андреевич Марков, 1856-1922) stands at a vertex,

A

, of an icosahedron. After every minute, he travels to one of the five adjacent vertices, along an edge, with equal probability. After 31 hours and 57 minutes (having traveled exactly 1917 times), is he more likely to be back at point

A

or at the opposite point

B

of the icosahedron?

Bonus question : After 1917 minutes, is Markov more likely to be at a vertex adjacent to A or at a vertex adjacent to B?

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

1 solution

Moderator note:

That is a very interesting Markov chain structure!

I'll come back to this later. Let p ( n , k ) be the probability Comrade Markov is found at vertex k after n moves. We can see that, for example, p ( 1 , A ) = 0 , i.e., after one move, the probability is 0 that he'll be found at vertex A . After a while, this probability function will approach 1 2 1 for large n , but never exactly . There is never a point in time when it exactly becomes 1 2 1 for all k . Hence, there is likely to be some difference between p ( 1 9 1 7 , A ) and p ( 1 9 1 7 , B ) . What is that difference, I'm not sure, it's likely to be incredibly tiny, but not zero! .

Log in to reply

I believe that Comrade Otto is correct.

I also believe that the probability that, after 31 hours and 57 minutes, Markov is at a vertex adjacent to A is equal to the probability that he is at a vertex adjacent to B plus the (miniscule) probability that he returns to A immediately after every single time he leaves it.

Log in to reply

Yes, exactly, Comrade Peter!

With the terminology I introduced, we have a 2 n − b 2 n = c 2 n + 1 − d 2 n + 1 = 5 n 1 .

Log in to reply

@Otto Bretscher – Well said comrade. Also, a 2 n + b 2 n − 2 c 2 n = 5 2 n 1 (from which we could solve explicitly if desired).

I claim that the difference is indeed 0... do you find a flaw in my argument?

Log in to reply

Before I tackle on the actual probabilities in this scenario involving the icosahedron, let's look at a much simpler example of an equilateral triangle, with vertices 1 , 2 , 3 , where Markov starts at one of them, and we examine the probabilities p ( n , k ) of arriving at the vertices after n jumps. Let's say that for some n , the probabilities are all exactly 3 1 . Then let p 1 , p 2 , p 3 be the probabilities of arriving at the vertices after n − 1 jumps. From this, we know that

2 1 ( p 1 + p 2 ) = 2 1 ( p 2 + p 3 ) = 2 1 ( p 3 + p 1 ) = 3 1

and deduce that p 1 , p 2 , p 3 = 3 1 . We can thus keep working backwards right up to n = 0 , which leads to a contradiction.

Log in to reply

@Michael Mendrin – I think that number of all the outcomes is n = 5 1 9 1 7 ⇒ n / 1 2 is not an integer which means that all vertices can not have same probabilities of outcome.

Let n a , n a i , n b i , n b be number of outcomes for vertex A , A i , B i , B respectively where A i is adjacent to A and B i is adjacent to B . Because of symmetry all n a i have equal values and all n b i have equal values. Therefore it can be written: 5 ∗ n a i + 5 ∗ n b i + n a + n b = 5 1 9 1 7 Number theory could be applied for the analysis of that equation. n a + n b has to be divisible by 5 ⇒ n a = n b ? ?

A computer program can be written to check it exactly.

Log in to reply

@Maria Kozlowska – Nobody claims that all vertices have the same probability of outcome, Comrade Maria, just A and B after an odd number of moves.

Log in to reply

@Otto Bretscher – On such occasion as Nov 11, Remembrance Day in Canada, anniversary of the end of the "war to end all wars", I have no choice but to sign armistice. For now I will stop trying make sense of history. You might be right, it would take more work on my part to check it. My bet is that it alternates between: even, A more likely, B more likely.

Log in to reply

@Maria Kozlowska – Have a good Remembrance Day, Comrade, and Narodowe Święto Niepodległości.

You say "my bet is".... I accept your bet! (I claim that it is never more likely that he is at B)

Log in to reply

@Otto Bretscher – Thanks. 97 years ago Poland was placed again on a map of Europe after over 120 years. To make up for it it was a period when we had our best poets: Mickiewicz, Słowacki, Krasiński and Norwid, and of course our best composer Chopin

When saying bet, I meant guess. I take that yours, Michael's and Peter's analysis is correct. Very interesting problem. We studied stochastic processes at university ( it was even separate subject), but I have not used math for years, so I do not remember much. I am sure there are theorems and formulas to apply to a case like this one.

Log in to reply

@Maria Kozlowska – Speaking of historic years in Poland, I do own a curious a stained glass armorial with the prominently shown date "1569", which is the year of the Union of Lublin. I've not quite figured out if the stained glass, most probably made around 1600, is supposed to commemorate that Union.

Log in to reply

@Michael Mendrin – This could be an indication Rzeczpospolita coat of arms There was some discussion on the Union of Lublin before the referendum for European Union. Some claim that Union of Lublin is very good example of the union between countries. I think that Scotland - England union was inspired by the Union of Lublin.

Good place to look for information on history of Poland is Norman Davies

Log in to reply

@Maria Kozlowska – I went and pulled out the stained glass armorial out of storage to remind myself of the details. There is a coat of arms, but it's very simple and looks like a family coat of arms (an axe and a scythe). Yet, the man in the picture has gold armor, Middle or Eastern European style, holding a costly arquebus--not something you'd expect from a common musketeer! I've still not made sense out of this stained glass work or why it was made. My best guess is that it was commissioned by a wealthy family, and the rank of the musketeer was sought after. The date could be just a coincidence, it could be the year the man got married to the woman in the picture, or the year he joined the ranks of the musketeers.

@Maria Kozlowska – Thanks for the link to Chopin! Beautiful!

I think the standard work on Markov Processes is by Comrade E.B. Dynkin, and I remember studying this topic in high school where we used a delightful little booklet by Comrades E.B. Dynkin and W.A Uspenski, "Matematicheskiye Besedy".

@Michael Mendrin – You might also consider the original question (with icosahedron) but with only three moves instead of 1917. The case where his second move is back to A is irrelevant, since then he cannot end up on either A or B. The remaining cases are symmetrical giving equal probabilities (2/25) that he will be at A or B after the third move.

Log in to reply

@Peter Byers – Oh, you're arguing that after Markov makes his first move, from that point on, the probabilities of arriving at either A or B is always equal, while not necessarily 1 2 1 . Let me think about that.

Edit: Okay, if this were true, it's not hard to see that the probabilities of arriving at the rest of the vertices would all be equal, while not necessarily equal to those for A , B . From this, we could extrapolate backwards towards n = 1 and see that this situation remains unchanged, i.e., while those for A , B remains equal, those for the rest also remains equal. This, again, leads to a contradiction.

Log in to reply

@Michael Mendrin – The work of Comrade Peter and myself shows that after an odd number of moves, Comrade Markov is equally likely to be at A and B , with probability a 2 n + 1 = b 2 n + 1 = 1 2 1 − 1 2 ∗ 5 2 n 1 ; this is also equal to the probability that after 2 n moves the Comrade is at any of the ten vertices other than A and B .

After an even number of moves, he is more likely to be back at A , with a 2 n − b 2 n = 5 n 1 . Likewise, c 2 n + 1 − d 2 n + 1 = 5 n 1 .

Log in to reply

@Otto Bretscher – When I get the chance, I'll offer my analysis of how to work out the probabilities. Then maybe we can see if we're having different interpretations of what this problem is about. I seem to recall having a similar argument with another guy, but that was some years ago.

Log in to reply

@Michael Mendrin – I'm looking forward to your analysis, Comrade Michael.

Log in to reply

@Otto Bretscher – Okay, finally I took the time to actually compute the probabilities for the first few moves. Column 1 is moves, 2 probability at A , 3 probability at vertices next to A , 4 probability at vertices next to B , 5 probability at B , 6 is 2 − 5 and 7 is 3 − 4 . One can see a clear pattern, which I didn't quite expect.

So, after all this ado, I must finally concede that, yes, for odd moves, A , B occur with equal probabilities.

⎝ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎜ ⎛ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 0 5 1 2 5 2 1 2 5 1 3 6 2 5 5 2 3 1 2 5 2 7 3 1 5 6 2 5 1 3 0 2 7 8 1 2 5 6 5 7 3 3 9 0 6 2 5 3 2 5 5 2 0 5 1 2 5 2 1 2 5 1 3 6 2 5 5 2 3 1 2 5 2 7 3 1 5 6 2 5 1 3 0 2 7 8 1 2 5 6 5 7 3 3 9 0 6 2 5 3 2 5 5 2 1 9 5 3 1 2 5 1 6 3 0 7 3 0 0 2 5 2 1 2 5 8 6 2 5 5 2 3 1 2 5 2 4 8 1 5 6 2 5 1 3 0 2 7 8 1 2 5 6 4 4 8 3 9 0 6 2 5 3 2 5 5 2 1 9 5 3 1 2 5 1 6 2 4 4 8 0 0 0 2 5 2 1 2 5 8 6 2 5 5 2 3 1 2 5 2 4 8 1 5 6 2 5 1 3 0 2 7 8 1 2 5 6 4 4 8 3 9 0 6 2 5 3 2 5 5 2 0 0 0 . 2 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 4 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 8 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 1 6 0 0 0 0 0 . 2 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 4 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 8 0 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 1 6 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 ⎠ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎟ ⎞

Log in to reply

@Michael Mendrin – Thank you very much for taking the time to make this table! I'm glad we got this settled.

Log in to reply

@Otto Bretscher – Really, it turned out to be a more interesting problem than I thought it would be. It just goes to show you that intuition can be wrong so many times in mathematics.

Log in to reply

@Michael Mendrin – How do you think Comrade Markov might do on a dodecahedron? My guess is that the outcome would be very similar to the icosahedron, with equal probability to be at the starting point A and the opposite point B after an odd number of moves, and equal probability to be at a neighbor of A or B after an even number of moves... but I would have to "do the math" to be sure.

Log in to reply

@Otto Bretscher – I suspect probably with similar "unexpected" results. You know, the behavior of the probabilities in this example does remind me of some cellular automata behavior. You never know can pop up.

How do you think Comrade Markov might do on a dodecahedron? My guess is that the outcome would be very similar to the icosahedron, with equal probability to be at the starting point A and the opposite point B after an odd number of moves

Yes, that is the case. (Well, unless I made a mistake of course. I only did it in my head.)

Oh, you're arguing that after Markov makes his first move, from that point on, the probabilities of arriving at either A or B is always equal,

Well, except for one thing: that statement omits the crucial condition that the number of moves was odd (see Otto's original post).

Let a n , b n , c n and d n be the probabilities that after n moves Comrade Markov is at A, at B, at a neighbor of A, or at a neighbor of B, respectively. The rules of the game and the geometry of the icosahedron imply that a n + 1 = 5 1 c n , b n + 1 = 5 1 d n , c n + 1 = a n + 5 2 c n + 5 2 d n , and d n + 1 = b n + 5 2 c n + 5 2 d n . Thus, if a n = b n , then c n + 1 = d n + 1 and if c n = d n then a n + 1 = b n = 1 . Since c 1 = 1 , we have a 1 = b 1 = 0 . Thus a n = b n for all odd n , and, in particular, Comrade Markov is equally likely to be at A and B after 1917 moves.