Number Of Digits In Powers Of Two

Let a k denote the number of digits in 2 k . For instance, since 2 4 = 1 6 , we have a 4 = 2 .

Compute the limit

n → ∞ lim n 2 1 k = 1 ∑ n a k .

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

2 solutions

Great, I saw the Stolz Cesaro Theorem after a long time. However, there was this question number 3, and in this contest the solution I gave was by an observation, that given any n, the number of n digit powers of 2 is either 4 or 3. Using that fact here may also lead us to the answer.

Log in to reply

I don't see the relevance to your RMO question to this question. If I'm not mistaken, by diophantine equations - modular arithmetic considerations , when 2 r and 2 s has the same number of digits, the remainder when 2 r is divided by 9 as compared to 2 s when divided by 9 for r = s . So this has nothing to do with limits or calculus in general.

Log in to reply

Yes that was the way I did the RMO problem, but what I wanted to say was that the problem required the observation that I stated above, so that as n tends to infinity, I can assume that the series a i is less than 3 ( 1 + 2 + 3 + . . . ) and greater than 4 ( 1 + 2 + 3 + . . . ) which are two extreme cases in which I assume that for every natural number i, there are exactly 3 i-digit powers of 2 in the first sum, and for every natural i exactly 4 i-digit powers of 2 in the second sum, so that the actual case, that is what the actual number of i-digit powers of 2 are, is an intermediate between these two. ( For some i, the number of i-digit powers of 2 are 4, and for some it is 3, so that the sum of such a series is actually intermediate between the two extreme sums shown above)

Now we note that the sums above within the brackets are not up to n , rather they are up to m , where m is the solution to the equation 2 m ( m + 1 ) = 3 n in the first case and 2 m ( m + 1 ) = 4 n in the second case. Now, we evaluate the sum for both the cases, and then divide both side by n 2 and since our required expression is an intermediate between these two values, we take the limit on both sides at n going to infinity and then apply the squeeze theorem to get the same result.

I was not referring to that problem, rather I was referring to the idea that I used in that problem, that I said in the previous comment.

My method is anyway of less rigor than yours, so do point out any gaps in my argument. :)

Log in to reply

@Soumava Pal – Most of your arguments sound very intuitive, but proving them is much harder than you think.

Can you show me your workings? Because I'm not sure whether you managed to explain them in your solution or you have glanced them over...

Log in to reply

@Pi Han Goh

–

@Pi Han Goh

You are right. I did not work out any part of the problem. I was just trying to find a way. I knew the answer from beforehand because I had done it earlier, using Cesaro only, but this time since you had already given that solution, I was trying a different approach. :P

Sorry for spamming.

Log in to reply

@Soumava Pal – Haha, don't need to apologize. We're all helping each other here!

Log in to reply

@Pi Han Goh – Thanks! :D

@Pi Han Goh – Can you please help me with these ?

Why does (n+1)log 10 2+1≤⌊(n+1)log 10 2+1⌋≤(n+1)log_10 2+2? Shouldn't the floor(x)<=x<x+1 instead of x < =floor(x) <= x+2

Log in to reply

No, you might want to brush up on the definition of the floor function .

Log in to reply

Really? Why is that? The first thing I see when I go to the floor function website is this: "In general, ⌊x⌋ is the unique integer satisfying ⌊x⌋≤x<⌊x⌋+1."

Log in to reply

@Liam Kell – You said: "Shouldn't the floor(x)<x<x+1 instead of x < floor(x) < x+2"

If we let x = 3 , then your equation becomes 3 < 3 < 4 , which is obviously false.

Log in to reply

@Pi Han Goh – I couldn't type less than or equal to on my computer. "In general, ⌊x⌋ is the unique integer satisfying ⌊x⌋≤x<⌊x⌋+1."

Log in to reply

I still don't understand your dispute. Can you clarify on which line (that I've added red numbers on the right) that you're disputing?

Log in to reply

@Pi Han Goh – Oh line number 4. Hold on.

Log in to reply

@Pi Han Goh – I've fixed it. Thanks for pointing it out. And I'm sorry for dismissing you earlier.

Let c = lo g 1 0 2 . Observe that a n = ⌊ lo g 1 0 2 n ⌋ + 1 = ⌊ c n ⌋ + 1 = c n + O ( 1 ) . Now, the limit follows easily: n → ∞ lim n 2 1 k = 1 ∑ n a k = n → ∞ lim n 2 1 k = 1 ∑ n c n + O ( 1 ) = n → ∞ lim 2 n c ( n + 1 ) + O ( 1 / n ) = c / 2 = lo g 1 0 2 .

how did you deduce the second equality, how did you solve the summation and why did O(1 ) become O(1/n) note: I understand the big O notation(O(1)) but I don't get the logic

Synopsis : We use the properties of a logarithm to figure the general formula for a k . We then note that the limit of the expression consists of a ratio of two functions, the latter function is a strictly monotone and divergent sequence. So we can apply Stolz–Cesàro theorem to compute a simpler limit in hopes that if this new limit exists then so does, the limit in question and they are both equal in value. We then evaluate this simpler limit by accompanying a simple theorem: Squeeze theorem .

Recall that by properties of logarithms , we can compute the number of digits of number (written in decimal representation) m to be ⌊ lo g 1 0 m + 1 ⌋ . So in this case, we have a k = ⌊ lo g 1 0 2 k + 1 ⌋ = ⌊ k lo g 1 0 2 + 1 ⌋ .

And we want to evaluate the limit, n → ∞ lim n 2 a 1 + a 2 + ⋯ + a n .

Because the expression the denominator in the fraction is n 2 , which is a strictly monotone and divergent sequence, we can apply Stolz–Cesàro theorem , which states that

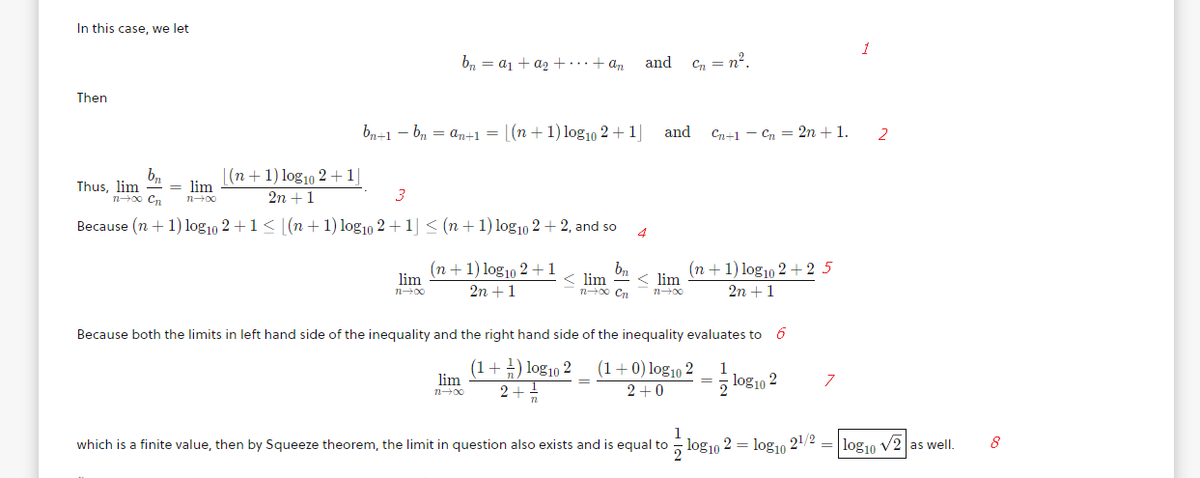

In this case, we let b n = a 1 + a 2 + ⋯ + a n and c n = n 2 . Then b n + 1 − b n = a n + 1 = ⌊ ( n + 1 ) lo g 1 0 2 + 1 ⌋ and c n + 1 − c n = 2 n + 1 .

Thus, n → ∞ lim c n b n = n → ∞ lim 2 n + 1 ⌊ ( n + 1 ) lo g 1 0 2 + 1 ⌋ .

Because z − 1 < ⌊ z ⌋ ≤ z . We have ( n + 1 ) lo g 1 0 2 < ⌊ ( n + 1 ) lo g 1 0 2 + 1 ⌋ ≤ ( n + 1 ) lo g 1 0 2 + 1 , and so

n → ∞ lim 2 n + 1 ( n + 1 ) lo g 1 0 2 < n → ∞ lim c n b n ≤ n → ∞ lim 2 n + 1 ( n + 1 ) lo g 1 0 2 + 1

Because both the limits in left hand side of the inequality and the right hand side of the inequality evaluates to n → ∞ lim 2 + n 1 ( 1 + n 1 ) lo g 1 0 2 = 2 + 0 ( 1 + 0 ) lo g 1 0 2 = 2 1 lo g 1 0 2

which is a finite value, then by Squeeze theorem, the limit in question also exists and is equal to 2 1 lo g 1 0 2 = lo g 1 0 2 1 / 2 = lo g 1 0 2 as well.