Paraboloid Surface Dynamics

A massive particle is confined to a paraboloid surface:

x = r cos θ y = r sin θ z = r 2

At time t = 0 , the position and velocity are ( θ is in radians):

r = 1 θ = 0 r ˙ = 1 θ ˙ = 1 0

What is the z coordinate of the particle at t = 2 8 ?

Note:

The ambient gravitational acceleration is

1

0

in the negative

z

direction

Bonus:

Plot the trajectory out to

t

=

1

0

0

The answer is 3.18.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

2 solutions

@Mark Hennings Very nice analytical solution. I just upvoted.

Solution based on the Lagrangian approach. This solution does not take a deep dive into the salient features of this dynamical system, even though there are several insights to explore. Let the mass of the particle be unity. The kinetic energy of the system is:

T = 2 1 m ( x ˙ 2 + y ˙ 2 + z ˙ 2 ) ⟹ T = 2 r ˙ 2 r 2 + 2 r ˙ 2 + 2 θ ˙ 2 r 2

Potential energy:

V = m g z = 1 0 r 2

System Lagrangian: L = T − V

Lagrange's equations read:

d t d ( ∂ r ˙ ∂ L ) − ∂ r ∂ L = 0 d t d ( ∂ θ ˙ ∂ L ) − ∂ θ ∂ L = 0

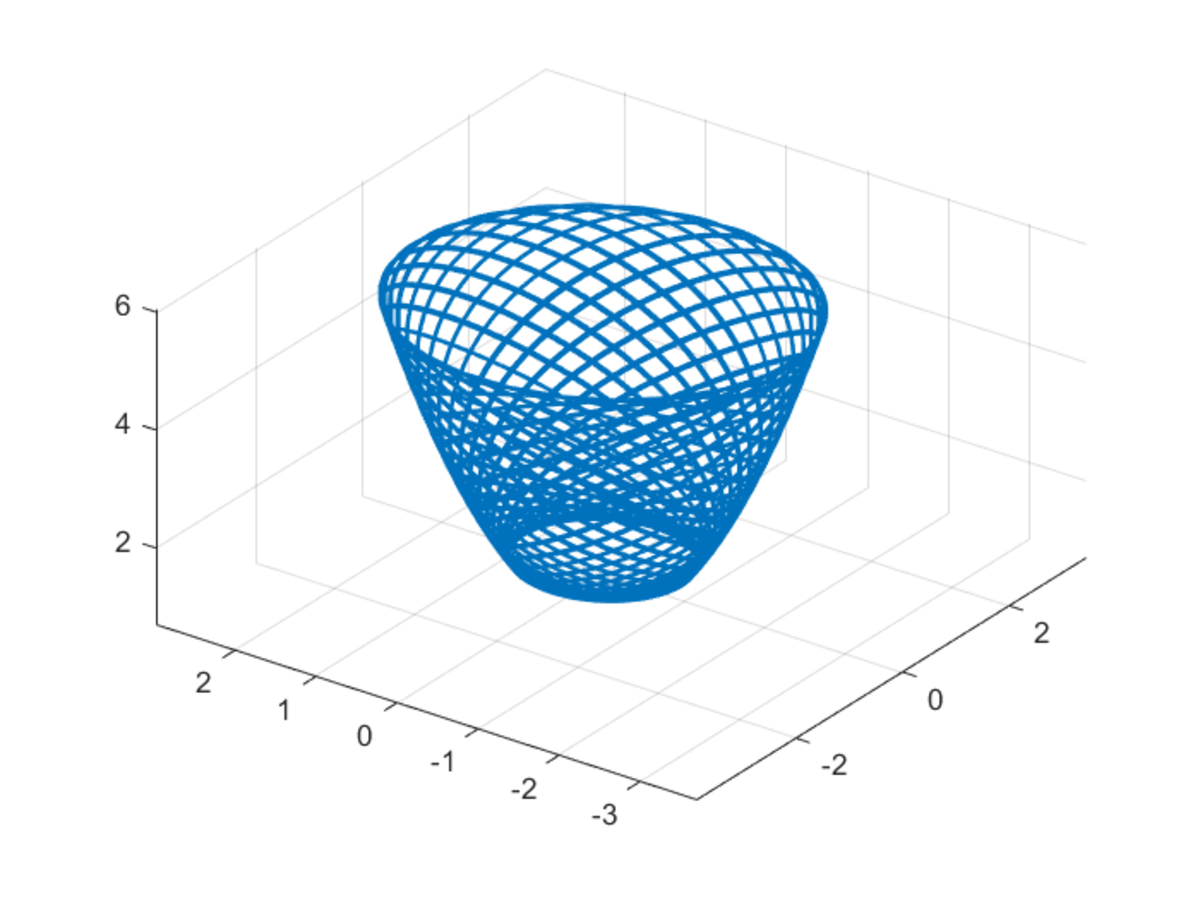

Finding the equations and numerically solving yields the required answer. The trajectory of the particle up to t = 1 0 0 :

@Karan Chatrath sir can you please help me in this question, lim

x

2

(

s

i

n

x

)

6

0

0

0

x

6

0

0

0

−

(

s

i

n

x

)

6

0

0

0

x tends to 0

Thanks in advance.

Solve without using expansion

Log in to reply

I do not know how to do it without an expansion. Please show your attempt.

Log in to reply

I guess you could say that the result is the limit as x → 0 of x 2 1 − ( x sin x ) 6 0 0 0 and attempt to use de l'Hopital's rule, but the result would be very messy indeed.

Log in to reply

@Mark Hennings – I thought about this approach as well but I rejected it thinking as follows:

Normally, de l'Hopital's rule applies to indeterminate forms: 0 0 or ∞ ∞ . In this case, the expression that you wrote can be stated in words as the difference between a constant and an indeterminate form, divided by zero. Is this strictly speaking one of the two aforementioned forms? Can l'Hopital's rule be applied to such a case? I do not think so, but I am not sure, and so I ask.

Log in to reply

@Karan Chatrath – f ( x ) = 1 − ( x sin x ) 6 0 0 0 is a perfectly nice differentiable function on R , with f ( 0 ) = f ′ ( 0 ) = 0 and f ′ ′ ( 0 ) = 2 0 0 0 . Of course, we are using de l'Hopital's rule a number of times to determine these results. Once we have these, we use de l'Hopital's rule again to get the answer...

Log in to reply

@Mark Hennings – @Mark Hennings Exactly sir. Sir while differentiating again and again are you following a particular trend.?? So that by following that trend we can differentiate it 6000 times? I think?

@Mark Hennings – Thank you for the clarification

Log in to reply

@Karan Chatrath – @Karan Chatrath Sir did you get the correct answer without using expansion??

Log in to reply

@A Former Brilliant Member – I shouldn't think so. It is so much easier to know that sin x = x − 6 1 x 3 + ⋯ . That is all we need to get the answer.

Sir are you an engineer as well?

Log in to reply

Yes, I studied mechanical engineering.

Log in to reply

Which university, if I may be so bold?

Log in to reply

@Krishna Karthik – Thanks for asking, but I prefer to withhold those details. I will display my qualifications on my profile if I change my mind someday.

Log in to reply

@Karan Chatrath – Fair enough. Your problems and solutions are quite interesting. I'd like to see some more classical mechanics problems!

Log in to reply

@Krishna Karthik – Thanks! My frequency of posting problems is lower than posting solutions. Nevertheless, I will try to come up with a few interesting ones in the coming days.

Parametrizing the position of the particle with z and θ , the kinetic energy of the particle is T = 2 1 m ( 1 + 4 z 1 ) z ˙ 2 + 2 1 m z θ ˙ 2 and the potential energy is V = m g z = 1 0 m z so the Lagrangian is L = 2 1 m ( 1 + 4 z 1 ) z ˙ 2 + 2 1 m z θ ˙ 2 − 1 0 m z Since L is independent of θ , we deduce that ∂ θ ˙ ∂ L is constant, and hence that z θ ˙ = 1 0 This is conservation of angular momentum. The other equation of motion is d t d ( ∂ z ˙ ∂ L ) d t d [ ( 1 + 4 z 1 ) z ˙ ] ( 1 + 4 z 1 ) z ¨ − 8 z 2 1 z ˙ 2 d z d [ 2 1 ( 1 + 4 z 1 ) z ˙ 2 ] = ∂ z ∂ L = − 8 z 2 1 z ˙ 2 + 2 1 θ ˙ 2 − 1 0 = z 2 5 0 − 1 0 = z 2 5 0 − 1 0 and hence ( 1 + 4 z ) z ˙ 2 = 5 0 0 z − 4 0 0 − 8 0 z 2 = 8 0 ( z − α ) ( β − z ) where α = 8 1 ( 2 5 − 3 0 5 ) β = 8 1 ( 2 5 + 3 0 5 ) From this it is clear that the particle's height oscillates between α and β , with half-period T = ∫ α β 8 0 ( z − α ) ( β − z ) 1 + 4 z d z The substitution z = α cos 2 ϕ + β sin 2 ϕ is helpful here, giving T = 2 1 0 1 ∫ 0 2 1 π 2 7 − 3 0 5 cos 2 ϕ d ϕ This can be evaluated explicitly in terms of complete elliptic integrals, but we shall simply note that T = 1 . 2 5 2 6 8 .

It is also worth noting that, during each half-period, the particle moves through an angle Θ , where Θ = ∫ α β z z ˙ 1 0 d z = 2 1 5 ∫ α β ( z − α ) ( β − z ) 1 + 4 z z d z = 4 1 0 ∫ 0 2 1 π 2 5 − 3 0 5 cos 2 ϕ 2 7 − 3 0 5 cos 2 ϕ d ϕ = 4 . 7 7 4 8 3

To begin with, the particle needs to rise from its initial height of z = 1 to z = β . This takes time T 0 = ∫ 1 β 8 0 ( z − α ) ( β − z ) 1 + 4 z d z = 2 1 0 1 ∫ u 2 1 π 2 7 − 3 0 5 cos 2 ϕ d ϕ where u = sin − 1 β − α 1 − α , and hence T 0 = 1 . 1 9 5 8 1 .

At time t = T 0 + 2 1 T = 2 7 . 5 0 2 2 , the particle has completed a total of 1 0 2 1 full oscillations, and so at that time is at a height z = α . We need to find the height (during the next half-oscillation) that it has reached by time t = 2 8 . In other words, we need to find the height z such that ∫ α z 8 0 ( z − α ) ( β − z ) 1 + 4 z d z = 2 1 0 1 ∫ 0 v 2 7 − 3 0 5 cos 2 ϕ d ϕ = 0 . 4 9 7 8 1 where v = sin − 1 β − α z − α , and we deduce that the height at time t = 2 8 is 3 . 1 7 7 0 .