Perfect In-Shuffles

A magician is so good at shuffling that his shuffles are always perfect in-shuffles. That means his shuffles are done in the following two steps:

- Split the pile of cards exactly in half.

- Interleave the top half with the bottom half such that every second card is from the top half.

If he started with six cards and shuffled thrice, he would get the original arrangement back.

If he started with a deck of 52 cards, how many shuffles would he need to get the original arrangement back?

The answer is 52.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

10 solutions

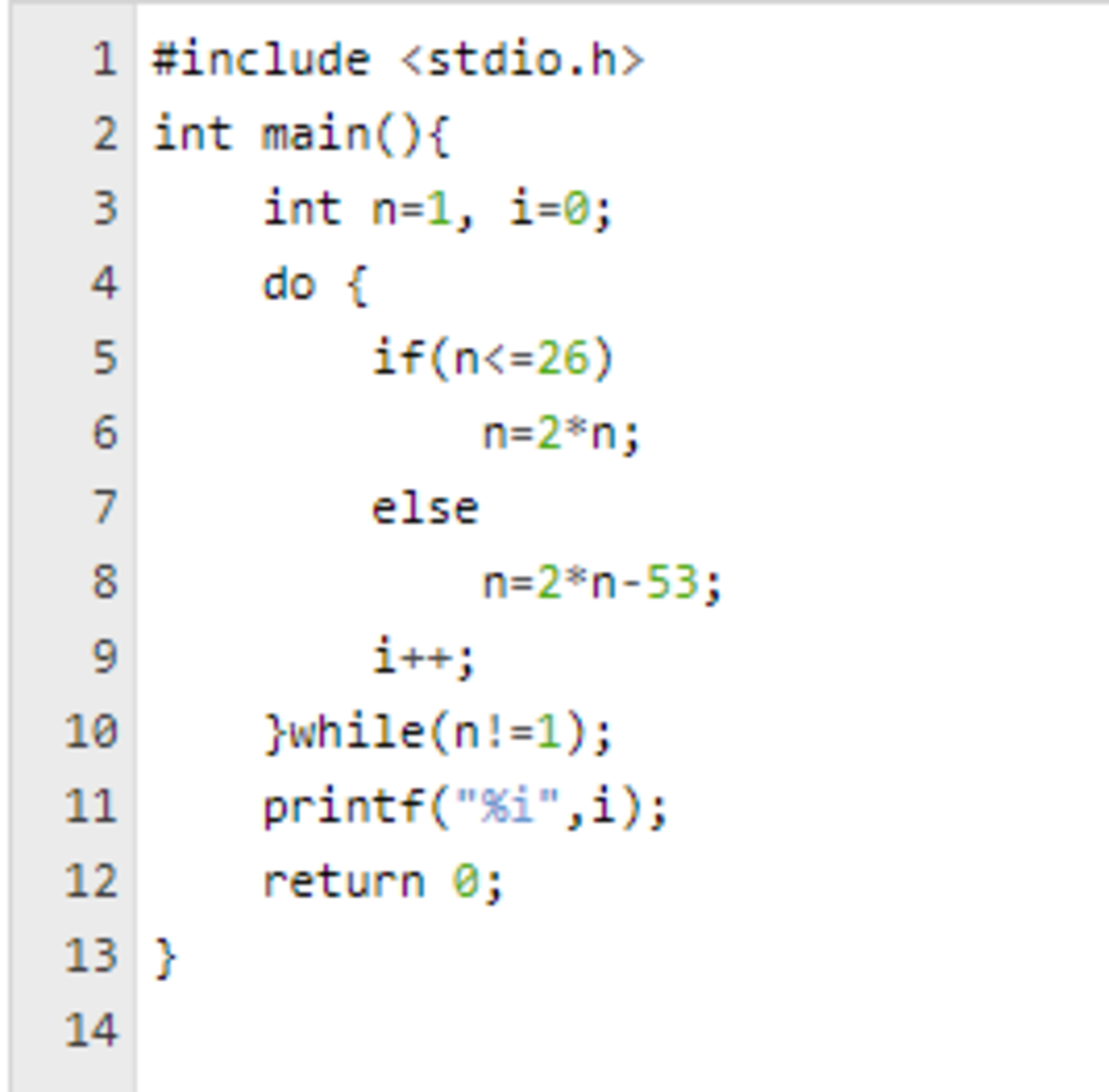

More succinctly, the mapping is j ↦ 2 j ( m o d 5 3 ) . It then remains to show that the smallest solution to 2 n ≡ 1 ( m o d 5 3 ) is n = 5 2 , or equivalently that 2 is a primitive root mod 53.

One could save some time by only calculating the cycle to element 26 since its length must be a divisor of 52.

Log in to reply

It is not true that all elements of the group S n of permutations of n symbols have order dividing n (you seem to be claiming that this is true for S 5 2 ). For example, S 5 contains ( 1 2 ) ( 3 4 5 ) , which has order 6 .

Log in to reply

To add on, the assumption that Keine was making is "the cycles of the elements have the same length". For example, it might have been possible that cards 1 and 52 just swap positions, while the other cards cycle through.

And that is why my interpretation of the group action as "multiplication by 2 in Z n + 1 " gives us so much more information. E.g. In the illustrated case of n = 6 , note that 2 3 ≡ 1 ( m o d 7 ) (hence 2 isn't a primitive root so the answer isn't 6).

(Edit: This line is false.) We know what the group action is, and can properly conclude that "the cycles have the same length" and that the "answer is the order of 2 mod n, hence is a divisor of n".

Log in to reply

@Calvin Lin – Agreed, the structure of Z 5 3 × is really useful, particularly since we know that it is a cyclic group of order 5 2 . In fact, the fact that the order of the shuffle is the order of 2 in this cyclic group is what makes Keine's observation true after all! We do need to note, however, that we are working with an element of C 5 2 , and not just an element of S 5 2 .

Log in to reply

@Mark Hennings – Oh, actually I lied in my last comment. Let me write it up properly.

So what size of cycle of this type, besides 6, will have its order less than its size?

Thanks for your solution Mark. There is one small mistake in your list, after the 50 there should follow a 47 (and then the 41). (50-26)*2-1=47

Edit: Thanks Calvin, I have corrected my mistake.

Log in to reply

Thanks for checking the details and noticing that typo! It should be 5 0 → 4 7 → 4 1 . I have updated the entry accordingly.

Note that your arithmetic is incorrect, as ( 5 0 − 2 6 ) × 2 − 1 = 4 7 .

Thanks for spotting the typo...

8 was my answer...

I think it started getting the same number from 10 cards onwards.

This is a generalization where n = 2 6 is used in the problem, and n = 3 is used in the illustrated example.

As Mark pointed out, the permutation is:

j ↦ 2 j , n + j ↦ 2 j − 1 ( 1 ≤ j ≤ n )

Notice that we can simplify this to j ↦ 2 j ( m o d 2 n + 1 ) , where we restrict to the cannonical residue classes (IE from 0 to 2 n ).

Let's write this out explicitly.

Consider

Z

2

n

+

1

×

, where the

×

indicates that we removed the 0 element (and there is no card corresponding to position 0).

Then, shuffling the cards can be represented as

ϕ

:

Z

2

n

+

1

×

→

Z

2

n

+

1

×

,

ϕ

(

x

)

=

2

x

.

The problem is equivalent to asking for the smallest

k

such that

ϕ

k

(

x

)

=

x

∀

x

. (This is equivalent to saying that

ϕ

k

is the identity function on

Z

2

n

+

1

.)

Clearly, if

k

=

o

r

d

2

n

+

1

(

2

)

, then by definition

2

k

≡

1

(

m

o

d

2

n

+

1

)

and hence

2

k

x

≡

x

(

m

o

d

2

n

+

1

)

∀

x

.

Conversely, by picking

x

=

1

, we require that

2

k

≡

1

(

m

o

d

2

n

+

1

)

. Hence,

k

must be a multiple of

o

r

d

2

n

+

1

(

2

)

.

Thus, this shows that the smallest

k

=

o

r

d

2

n

+

1

(

2

)

.

For

n

=

3

, we can check that

2

1

≡

2

,

2

2

≡

4

,

2

3

≡

1

(

m

o

d

7

)

, and hence

k

=

o

r

d

7

2

=

3

.

For

n

=

2

6

, it requires a bit of work to check that

2

4

≡

1

(

m

o

d

5

3

)

and

2

2

6

≡

1

(

m

o

d

5

3

)

, in order for us to conclude that since the order is a divisor of 52, but not a divisor of 4 or 26, hence it can only be 52.

Food for thought:

- True or false: The answer must divide 2 n . (Hint: False. What is the smallest counterexample?)

- True or false: Fix n . Each card cycles through the same number of positions. (Hint: False. What is the smallest counterexample?)

- How does this change if there is an odd number of cards? The bottom half would have more cards, so that every second card is from the top half.

(Read the comments after you have thought about this.)

In general, Z 2 n + 1 is a ring, but not a field. Consequently, the set Z 2 n + 1 × of nonzero numbers modulo 2 n + 1 does not form a group (except when 2 n + 1 is prime). However the set U ( Z 2 n + 1 ) of numbers modulo 2 n + 1 that are coprime to 2 n + 1 (the units of Z 2 n + 1 ) do form a group of order ϕ ( 2 n + 1 ) , and 2 is an element of this group. Thus the order of 2 divides ϕ ( 2 n + 1 ) .

If n is 1 , 2 , then 2 n + 1 is prime and 2 is a primitive root, so generates a 2 n -cycle. If n = 3 then 2 n + 1 is prime, but 2 is not a primitive root. It generates the 3 × 3 -cycle ( 1 2 4 ) ( 3 6 5 ) .

When n = 4 we see that ϕ ( 9 ) = 6 = 8 , so we are likely to have problems. As a unit, 2 has order 6 , and it generates the permutation ( 1 2 4 8 7 5 ) ( 3 6 ) . This makes the answer to both question 1 and question 2 "false, consider n = 4 ".

If there are an odd number of cards, the bottom card always stays on the bottom, and we are performing a perfect in-shuffle on the other cards on top of it

Log in to reply

Perfect! After making a false comment, I decided to layout the underlying structure of the shuffle, in which case our understanding of abstract algebra allows us to conclude what is going on.

To provide a more layman explanation of the food for thought:

- In actuality, the answer must divide ϕ ( 2 n + 1 ) . In the cases where 2 n + 1 is prime (e.g. n = 3 , 2 6 ) then ϕ ( 2 n + 1 ) = 2 n and so the answer must divide 2 n . In cases when 2 n + 1 is composite, then we cannot conclude that the answer must divide 2 n .

- Each card cycles through the same number of positions if and only if the smallest positive integer value of k i satisfying 2 k i × i ≡ i ( m o d 2 n + 1 ) is the same for all i . The latter is clearly true if 2 n + 1 is prime. If 2 n + 1 is composite, I do not yet know if this could be true. For example, when 2 n + 1 = 9 , we obtain the cycles ( 1 2 4 8 7 5 ) ( 3 6 ) .

- Using the language in the solution, the bottom card corresponds to the residue class of 2 n + 1 , and the permutation is ϕ : Z 2 n + 1 → Z 2 n + 1 , ϕ ( x ) = 2 x . We can make similar conclusions about the behvaiour, and in particular, as Mark pointed out, 0 will always be in it's own orbit.

Log in to reply

For 2, why they are equivalent?

Log in to reply

@Wong Kwym – Ah, that is a good point. I don't see a proof of that as yet, so I changed it to a single-sided implication.

Recognising that for an odd number of cards, if the odd card were in the second pile the last card would always remain last (contrary to Matt 20:16), I put the odd card in the FIRST pile. (I know that the last 2 cards in the first pile will therefore remain adjacent, but only in the first shuffle). This produced some amusing results: for 2n+1 = 13 there were 2 sub-cycles of 4, one of 3 and one of 2, so 12 shuffles are required (LCM of 2,3,4). For 2n+1 = 15 there were sub-cycles of 7 and 8, so to return to starting point we require 56 shuffles. And so on. Whenever 2n cards required 2n shuffles to return to the starting position, then 2n-1 cards required 2n-1 shuffles. This is pretty obvious, come to think about it, as both situations involve doubling mod 2n+1, so the sequences are the same apart from position n in the 2n-1 pack then becoming 2n-1, so that the sequence is n, 2n-1, 2n-3 ..., whereas for the 2n pack it's n, 2n, 2n-1, 2n-3, ...

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

|

5 2

This is optimizable:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 |

|

Output:

1 2 3 4 |

|

Python

l = [i for i in range(52)]

def s(l):

p = []

a = l[:len(l)/2]

b = l[len(l)/2:]

for i in range(len(l)/2):

p.append(b[i])

p.append(a[i])

print p

return p

print l

for i in range(1, 53):

print i

l = s(l)

The way I saw it, the first card has to travel down one side and back up the other, 26 times each way.

include<iostream>

define N 60

define M 52

using namespace std;

int card[N],card1[N];

void change(int arry[])

{

for(int i=1;i<=M/2;i++)

{

card1[2

i-1]=card[M/2+i];

card1[2

i]=card[i];

}

for(int j=1;j<=M;j++)

card[j]=card1[j];

}

int main()

{

int cnt=0,flag=0;

for(int i=1;i<=M;i++)

card[i]=i;

while(flag==0)

{

flag=1;

change(card);

cnt++;

for(int i=0;i<=M;i++)

if(card[i]!=i)

{

flag=0;

break;

}

}

printf("%d\n",cnt);

return 0;

}

Solution in Microsoft Excel VBA

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 |

|

If the cards positions are numbered 1 to 5 2 (with 1 being the top card), then the perfect Faro in-shuffle (as it is called) provides the following permutation of the cards: j ↦ 2 j , 2 6 + j ↦ 2 j − 1 ( 1 ≤ j ≤ 2 6 ) In cycle notation we discover that this is a 5 2 -cycle: ( 1 5 2 2 5 1 4 4 9 8 4 5 1 6 3 7 3 2 2 1 1 1 4 2 2 2 3 1 4 4 9 3 5 1 8 1 7 3 6 3 4 1 9 1 5 3 8 3 0 2 3 7 4 6 1 4 3 9 2 8 2 5 3 5 0 6 4 7 1 2 4 1 2 4 2 9 4 8 5 4 3 1 0 3 3 2 0 1 3 4 0 2 6 2 7 ) which therefore has order 5 2 .

If the riffle shuffle is done the other way, so that the top card always remains on top and the bottom card always remains on the bottom (this is the Faro out-shuffle), the order of the corresponding permutation is only 8 (a fact well-known to stage magicians).