Proximity to perfect squares

A function f ( n ) is defined over positive integers as follows:

f ( n ) = ⎩ ⎪ ⎨ ⎪ ⎧ 0 1 − 1 if n is a perfect square ; if n is closer to the perfect square before it than to the one after it ; otherwise .

For example, f ( 1 ) = 0 because 1 is a perfect square; f ( 2 ) = 1 because 2 is closer to 1 than it is to 4; f ( 7 ) = − 1 because 7 is closer to 9 than it is to 4.

What can be said about the series n = 1 ∑ ∞ n f ( n ) ?

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

10 solutions

If we collect terms around a square, their sum would be about quartic over n, so the tail would be a third power. This way we obtain the convergence of order 1.5: summing 1000000 terms we get precision about 1e-9. And if we finally add the tail approximation 1 / 6 n 3 , we get even better precision.

It was so easy!!! take the sum out to any sqared no. of terms. It is always zero... p.s. the series is always convergent....

Log in to reply

I don't understand what you mean. The partial sums are never 0, and what series is always convergent?

Log in to reply

Take the sums upto any perfect sq. terms (ex- 9 , 16, 36,49.... no. of terms). Sums are always 0;

Log in to reply

@Arijit Dey – That is not the case. You should check the problem description again.

Log in to reply

@Leonel Castillo – I see but there is no restriction on number of terms :-)

@Leonel Castillo – Although there are an even number of integers between each perfect square, and therefore an equal number of f(n) terms with value 1 and -1, the problem asks for the sum of f(n) divided by n. As the integer values increase, f(n) divided by n gets smaller and smaller but is always slightly bigger for the positive terms. If the problem had asked for the sum of f(n) for an infinite number of terms this would have a value of either 1, 0 or -1 depending on the 'value' of infinity.

I think you are confusing the sum of f(n) with the sum of f(n)/n. While the sum of f(n) is 0 when taken up to a square number of terms, it does not converge; the partial sums can be both arbitrarily positive and arbitrarily negative infinitely often.

Could you please explain why it is safe to apply parenthesis here (first step of your proof)? For example if we consider sequence like this 1 − 1 + 2 1 + 2 1 − 2 1 − 2 1 + 4 1 + 4 1 + 4 1 + 4 1 − 4 1 − 4 1 − 4 1 − 4 1 + . . . and then apply parenthesis ( 1 − 1 ) + ( 2 1 + 2 1 − 2 1 − 2 1 ) + ( 4 1 + 4 1 + 4 1 + 4 1 − 4 1 − 4 1 − 4 1 − 4 1 ) + . . . we can "prove" that it converges to zero, or if we apply them another way 1 + ( − 1 + 2 1 + 2 1 ) + ( − 2 1 − 2 1 + 4 1 + 4 1 + 4 1 + 4 1 ) + ( − 4 1 − 4 1 − 4 1 − 4 1 + . . . ) - it will converge to 1. (actually, sequence in my example diverges, because partial sums does not converge). So why convergence of sequence with parenthesis means that initial sequence converge to the same value?

Log in to reply

It has to do with how much the original sequence can get away from the new sequence. This difference tends to 0 as n goes to infinity.

Note that X n = j = n 2 − n + 1 ∑ n 2 + n j f ( j ) = − j = 1 ∑ n − 1 n 2 − j 1 + j = 1 ∑ n n 2 + j 1 = n ( n + 1 ) 1 + j = 1 ∑ n − 1 ( n 2 + j 1 − n 2 − j 1 ) = n ( n + 1 ) 1 − 2 j = 1 ∑ n − 1 n 4 − j 2 j for all integers n ≥ 2 . Note that 2 j = 1 ∑ n − 1 n 4 − j 2 j ≤ 2 j = 1 ∑ n − 1 n 4 − n 2 j = n 2 ( n 2 − 1 ) n ( n − 1 ) = n ( n + 1 ) 1 for all n ≥ 2 , so we deduce that 0 ≤ X n ≤ n ( n + 1 ) 1 for all n ≥ 2 . Since j = 1 ∑ n 2 + n j f ( j ) = 2 1 + m = 2 ∑ n X m we deduce that j = 1 ∑ ∞ j f ( j ) is convergent, with limit less than 2 1 + ∑ m ≥ 2 m ( m + 1 ) 1 = 1 . Certainly, then, the limit is less than 2 .

To be picky, if we denote S n = ∑ j = 1 n j f ( j ) , we have so far shown that the subsequence S n 2 + n converges to some limit as n → ∞ . Since ∣ ∣ S m − S n 2 + n ∣ ∣ ≤ j = n 2 − n + 1 ∑ n 2 + n j 1 ≤ n 2 − n + 1 2 n ≤ n − 1 2 n 2 − n + 1 ≤ m ≤ n 2 + n we can now deduce that the entire sequence of partial sums S m converges.

If the limit is L , then 0 ≤ L − j = 1 ∑ n 2 + n j f ( j ) = m = n + 1 ∑ ∞ X m ≤ n + 1 1 and hence we deduce that the error term L − j = 1 ∑ n j f ( j ) tends to 0 as n → ∞ no faster than n − 2 1 .

Hello Mark Sir. Can you help me to work with the following problem.

n = 0 ∑ ∞ ( ( n + 1 ) ( n + 2 ) 1 + 1 ! 2 + 2 ! 3 + ⋯ n ! n + 1 ) ?

Log in to reply

You want n = 0 ∑ ∞ ( n + 1 ) ( n + 2 ) 1 ( j = 0 ∑ n j ! j + 1 ) = j = 0 ∑ ∞ n = j ∑ ∞ ( n + 1 ) ( n + 2 ) j ! j + 1 = j = 0 ∑ ∞ j ! j + 1 × j + 1 1 = j = 0 ∑ ∞ j ! 1 = e

Log in to reply

Thank you so much Sir !! You are indeed so awesome. :)

How do I learn Double series ? I was aware of it regarding this problem however, had no any idea about it .

Let's group the terms around a perfect square

n

2

1

.

∑

n

=

1

∞

n

f

(

n

)

=

(

2

1

)

+

(

−

3

1

+

5

1

+

6

1

)

+

(

−

7

1

−

8

1

+

1

0

1

+

1

1

1

+

1

2

1

)

+

(

−

1

3

1

−

1

4

1

−

1

5

1

+

1

7

1

+

1

8

1

+

1

9

1

+

2

0

1

)

+

…

.

In each group, we subtract off

n

−

1

terms that are larger than

n

2

1

, and add on

n

terms that are smaller than

n

2

1

. Thus, the total sum will be less than

−

(

n

−

1

)

×

n

2

1

+

n

×

n

2

1

=

n

2

1

.

Hence, we can conclude that

n = 1 ∑ ∞ n f ( n ) < 1 1 + 4 1 + 9 1 + … = 6 π 2 ≈ 1 . 6 4 4

We can tighten up the bound by accounting for the initial terms. For example,

∑

n

=

1

∞

n

f

(

n

)

<

2

1

+

4

1

+

9

1

+

…

=

2

1

+

6

π

2

−

1

≈

1

.

1

4

4

∑

n

=

1

∞

n

f

(

n

)

<

2

1

−

3

0

1

+

9

1

+

…

=

3

0

1

4

+

6

π

2

−

(

1

+

4

1

)

≈

0

.

8

6

∑

n

=

1

∞

n

f

(

n

)

<

2

1

−

3

0

1

−

9

2

4

0

5

9

+

…

=

9

2

4

0

4

2

5

3

+

6

π

2

−

(

1

+

4

1

+

9

1

)

≈

0

.

7

4

The next line (too ugly to write out) is

<

0

.

6

8

and the line after that is

<

0

.

6

4

.

Note: We can improve the bounding of each group. As Alexander Maly shows in the comments, each parenthesis is very slightly larger than 2 n 4 1 . 2 ζ ( 4 ) ≈ 0 . 5 4 1 1 , which is much closer to the true value.

Which terms in parentheses are negative? It looks they all are positive, asymptotically 1 / ( 2 n 4 ) .

I think, you should prove the fact about a sign of parenthesis groups.

Log in to reply

That looks easy. b n = − n 2 − n + 1 1 − n 2 − n + 2 1 − ⋯ n 2 − 1 1 + n 2 + 1 1 + ⋯ + n 2 + n 1 = − ∑ k = 1 n − 1 ( n 2 − k 1 − n 2 + k 1 ) + n 2 + n 1 = − ∑ k = 1 n − 1 n 4 − k 2 2 k + ∑ k = 1 n − 1 ( n 2 + n ) ( n 2 − n ) 2 k = ∑ k = 1 n − 1 ( n 4 − k 2 ) ( n 4 − n 2 ) 2 k ( n 2 − k 2 ) , because ∑ k = 1 n − 1 2 k = n 2 − n . Next, ∑ k = 1 n − 1 2 k ( n 2 − k 2 ) = 2 n 4 − n 2 , so 0 < 2 n 4 1 < b n < 2 ( n 4 − n 2 ) 1 , if n ≥ 2 . Q.e.d.

We can further rewrite b n − 2 n 4 1 = ∑ k = 1 n − 1 ( n 4 − k 2 ) ( n 4 − n 2 ) 2 k ( n 2 − k 2 ) − ∑ k = 1 n − 1 2 n 4 ( n 4 − n 2 ) 4 k ( n 2 − k 2 ) = ∑ k = 1 n − 1 n 4 ( n 4 − k 2 ) ( n 4 − n 2 ) 2 k 3 ( n 2 − k 2 ) ∈ ( 6 n 4 ( n 2 + 1 ) 1 , 6 n 6 1 ) .

Log in to reply

Great observation! That gets us very close to the actual bound. You should write that as a solution!

Thanks for your comments, I wrote this up quickly and made some wrong guesses.

Using symmetry, you can figure that it must be smaller than a certain number, which could eventually be figured as 2.

You can solve this intuitively. Square numbers add nothing to f(n) so all we are concerned with is the distance between consecutive, perfect squares.

If you take the distance between any two very large, consecutive, perfect squares and tally all of the scenarios resulting in (1)s and (-1)s you will notice that the tallies differ by at most 2. Let's say that we have a distance of 1,000,000 between two arbitrary perfect squares, the first 499,999 are (1)s and the last 500,000 are (-1)s, there is now a 50/50 chance that our last number is either a (1) or (-1). Regardless of who gets the tally, the percent total of each tally will be approximately 50%, and will continue to get closer to exactly 50% so we can deduce that the function converges somewhere around .5

I like this idea, and indeed the value is around 0.543512... like you say, but could you put this solution in more formal terms? I see that your results are correct, but I don't quite follow your idea.

Yes could you elaborate a little more please? What do you mean by "who gets the tally?" Thanks!

I don't know if my deduction is correct but what i thought is that, as the denominator keeps getting bigger and the numerator go from -1 to 1, it's not able to get higher than 2

We write the series as:

S = ( 2 1 − 3 1 ) + ( 5 1 + 6 1 − 7 1 − 8 1 ) ⋯ = k = 1 ∑ ∞ n = 1 ∑ k ( k 2 + n 1 − k 2 + k + n 1 ) = k = 1 ∑ ∞ n = 1 ∑ k ( k 2 + n ) ( k 2 + k + n ) k

Since n > 0 ,

( k 2 + n ) ( k 2 + k + n ) k < k 2 ( k 2 + k ) k

Therefore,

S < k = 1 ∑ ∞ n = 1 ∑ k k 2 ( k 2 + k ) k = k = 1 ∑ ∞ k 2 ( k 2 + k ) k 2 = k = 1 ∑ ∞ k ( k + 1 ) 1 = 1

So S converges to a value smaller than 1.

We can see that between two adjacent squared integers n , n + 1 , there are exactly 2 n integers. Half of them will contribute to the series with a plus sign, while the rest will get a minus sign. We can thus write the series as:

n = 1 ∑ ∞ ( k = 1 ∑ n ( k + n 2 1 − k + n 2 + n 1 ) ) We can express the above nested sum in terms of the digamma function ψ ( x ) , making use of the properties appearing in Digamma function , like ψ ( x + N ) − ψ ( x ) = ∑ k = 0 N − 1 x + k 1 . We have: n = 1 ∑ ∞ [ 2 ψ ( 1 + n + n 2 ) − ψ ( 1 + n 2 ) − ψ ( 1 + 2 n + n 2 ) ] We can then approximate the digamma function by: ψ ( x ) ≈ l n ( x ) − 2 x 1 + O ( 1 / x 2 ) , which gets better and better as we sum over larger integers. We can drop the logarithmic behaviour, since for large n, all three functions behave as 2 l n ( n ) . So n = 1 ∑ ∞ n f ( n ) ≈ n = 1 ∑ ∞ ( 2 ( n 2 + 1 ) 1 − 1 + n + n 2 1 + 2 ( 1 + 2 n + n 2 ) 1 ) If you work out the fractions, you can see that n = 1 ∑ ∞ ∣ n f ( n ) ∣ < n = 1 ∑ ∞ n 3 1 = 1 . 2 0 2 0 6 . The series is thus bounded by above and converges to a number smaller than 2

Nice idea, but in your last inequality you should drop the absolute value because the series is not absolutely convergent.

Log in to reply

Yes, you are right.In fact you can just take into account only the positive fractions, so you can establish an inequality with 1/n^2.

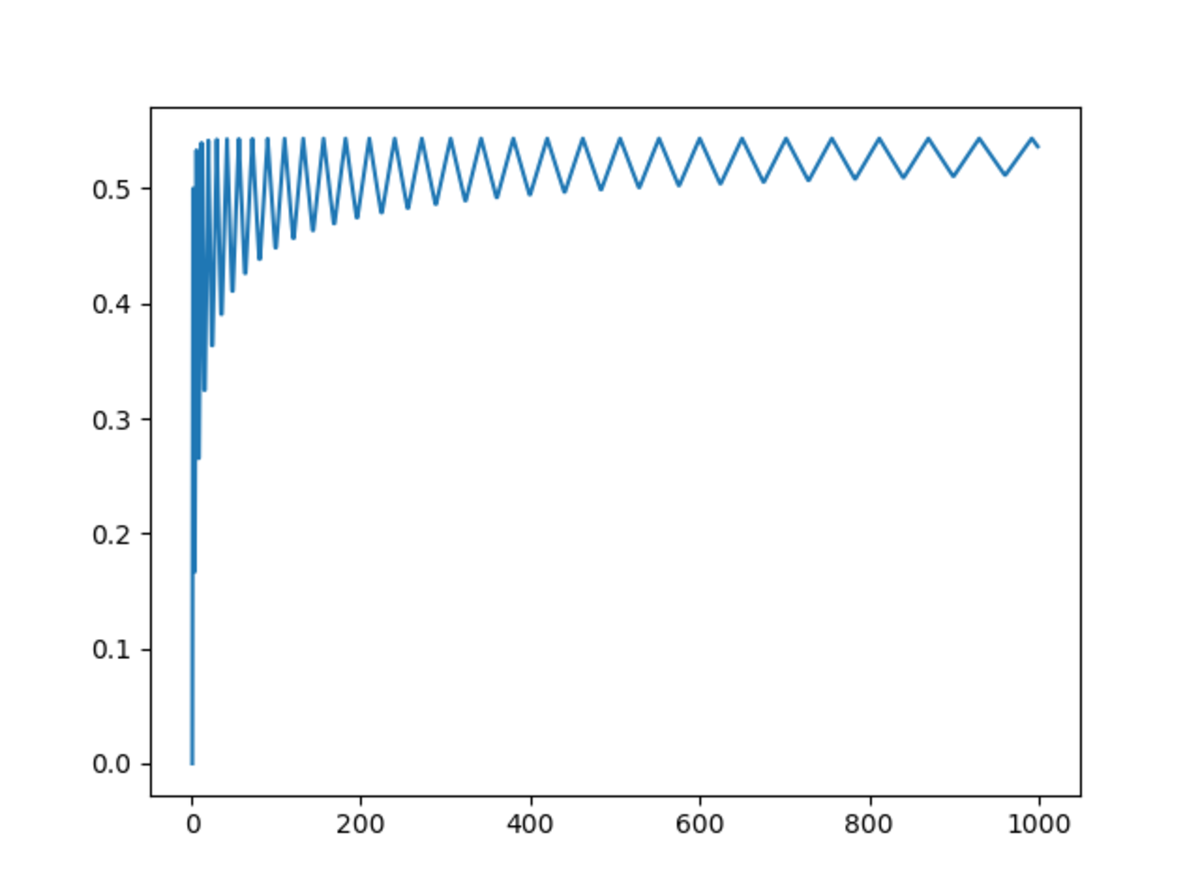

Kind of stupid approach: ask computer to calculate first 1000 sums

Obviously converges to something around 0.5

Obviously converges to something around 0.5

Yeah, it looks like it converges when x ≈ 1 0 0 0 , but does it converge when x → ∞ ?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

|

1 |

|

The first observation one should make is that this function has a special symmetry around square numbers. Take a look at the following values of the series:

∑ n = 1 ∞ n f ( n ) = 2 1 − 3 1 + 5 1 + 6 1 − 7 1 − 8 1 + 1 0 1 + 1 1 1 + 1 2 1 − 1 3 1 − 1 4 1 − 1 5 1 + . . . . If we group the terms that occur before the sum reaches perfect squares we get the following:

∑ n = 1 ∞ n f ( n ) = ∑ k = 1 ∞ ( ∑ n = 1 k k 2 + n 1 − ∑ n = 1 k ( k + 1 ) 2 − n 1 ) . This is basically a new infinite series that is equivalent to the previous one but has the property that every term of the infinite sum is a positive one. With this, we can start bounding. Notice that:

∑ k = 1 ∞ ( ∑ n = 1 k k 2 + n 1 − ∑ n = 1 k ( k + 1 ) 2 − n 1 ) ≤ ∑ k = 1 ∞ ( ∑ n = 1 k k 2 + 1 1 − ∑ n = 1 k ( k + 1 ) 2 − 1 1 ) = ∑ k = 1 ∞ k 2 + 1 k − ( k + 1 ) 2 − 1 k = ∑ k = 1 ∞ k 3 + 2 k 2 + k + 2 2 k − 1 ≤ ∑ k = 1 ∞ k ( k + 1 ) 2 2 k = ∑ k = 1 ∞ ( k + 1 ) 2 2 = 3 1 ( π 2 − 6 ) ≈ 1 . 2 8 9 . . .

For the last equality I used the known result that ∑ k = 1 ∞ k 2 1 = 6 π 2 .

Using a computer to compute this sum up to the 1000000th term I got 0 . 5 4 2 5 1 3 8 3 4 7 5 9 2 2 8 but the convergence is very bad. I can at least say that 0 . 5 4 . . . are true digits of the real value.

I added up to 1 0 1 2 terms to find 0 . 5 4 3 5 1 2 3 3 4 7 6 0 7 2 9 . . . and now I can confirm the digits up to 0 . 5 4 3 5 1 2 . . .