Sleeping Satellite

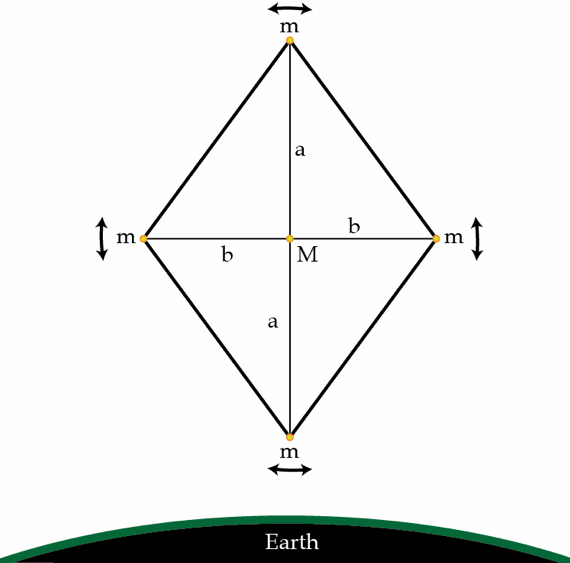

Consider a small geostationary satellite consisting of four point masses m connected by light rigid rods of length a and b to a central mass M ( M ≫ m ) as shown in the figure. In addition, four light rods of length a 2 + b 2 ensure that the satellite behaves as rigid body. It turns out that if b a > 1 , the satellite can oscillate about its center of mass in the plane of the orbit. In other words, the configuration showed in the figure is stable. For what ratio η = b a the period of small oscillations of the satellite equals its orbital period? Assume that the dimensions of the satellite are much smaller than the radius its orbit.

The answer is 1.414.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

3 solutions

When the satellite is tilted at an angle θ , the coordinates of its four masses can be broken down in the original coordinates as diagrammed in the figure below. Let the height of the mass M relative to the center of the Earth be R o , the radius of orbit.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Each mass is simultaneously pulled toward the Earth by gravity and pushed away from the Earth by the centrifugal force.

Consider the bottom most mass on the rod of length a . It experiences a gravitational pull of magnitude ( R o − a cos θ ) 2 G M E m as well as a centrifugal push of magnitude m ω 2 ( R o − a cos θ ) .

Similarly, the top mass, also on a rod of length a experiences experiences a gravitational pull of magnitude ( R o + a cos θ ) 2 G M E m as well as a centrifugal push of magnitude m ω 2 ( R o + a cos θ ) .

These forces act through the moment arm a sin θ . The gravitational force on the bottom mass is contributes torque in the counter clockwise direction (negative) as does the centrifugal force on the top mass. Likewise, the gravitational force on the top mass and the centrifugal force on the bottom mass both contribute positive torque. Multiplying these forces by their moment arms and summing we find the net torque on the top and bottom mass given by

− m ω 2 2 a 2 cos θ sin θ + ( R o + a cos θ ) 2 G M E m a sin θ − ( R o − a cos θ ) 2 G M E m a sin θ

Expanding the expression about θ = 0 to first order, we find that these terms contribute ( − 2 m ω 2 − ( R o 2 − a 2 ) 2 4 a 2 R o ) θ ≈ − ( 2 m ω 2 + G M E m R o 3 4 ) θ a 2

A similar calculation yields a contribution of ( 2 m ω 2 + G M E m R o 3 4 ) θ b 2 from the two masses on the rods of length b .

The overall torque is then τ = ( 2 m ω 2 + G M E m R o 3 4 ) θ ( b 2 − a 2 )

The torque on the satellite is balanced by its rotation, i.e. τ = d t d L = I θ ¨

The moment of inertia of the four points masses about the center of mass is given by I = m ( 2 a 2 + 2 b 2 ) . Therefore, we have

θ ¨ = ( 2 ω 2 + G M E R o 3 4 ) a 2 + b 2 b 2 − a 2 2 θ = ( ω 2 + G M E R o 3 2 ) 1 + η 2 1 − η 2 θ

where we have made the replacement η = b a .

This is just the pendulum equation for small angle oscillations and so the frequency of the system is given by the square root of the negative of the coefficient on θ . We can clearly see that the coefficient is negative for η > 1 as suggested in the problem, making it a stable oscillator in that regime.

We can make one further simplification in that the gravitational pull on the satellite is balanced perfectly by the centrifugal force upon it, i.e.

M t o t a l ω R o = R o 3 G M E M t o t a l and therefore ω 2 = R o 3 G M E .

The torque equation then becomes

θ ¨ = 3 ω 2 1 + η 2 1 − η 2 θ

and we get a self consistent relation for ω :

ω 2 = 3 ω 2 1 + η 2 η 2 − 1 → 1 + η 2 = 3 η 2 − 3 → 2 η 2 = 4 → η = 2

Here goes my solution:

I state it again, I am working in the CoM frame. Here is an image that goes with my solution:

Image

Image

Number the point masses starting from the bottom one (mark the bottom most as 1) and going clockwise

As stated in one of my previous reply, I have

r 1 1 = R 1 ( 1 + R a cos θ + 4 3 cos ( 2 θ ) + 1 R 2 a 2 )

r 2 1 = R 1 ( 1 + R b sin θ + 4 1 − 3 cos ( 2 θ ) R 2 b 2 )

r 3 1 = R 1 ( 1 − R a cos θ + 4 3 cos ( 2 θ ) + 1 R 2 a 2 )

r 4 1 = R 1 ( 1 − R b sin θ + 4 1 − 3 cos ( 2 θ ) R 2 b 2 )

I have used the same approximation I stated before to calculate the reciprocals of r 1 , r 2 , r 3 and r 4 .

The potential energy U of the system is

U = − r 1 G M e m − r 2 G M e m − r 3 G M e m − r 4 G M e m + C

where C is the potential energy of masses with respect to each other plus the potential energy of central mass with earth.

Plugging in the expressions for the reciprocal of distances and simplifying, I get:

U = − R G M e m ( 4 + 2 3 cos ( 2 θ ) + 1 R 2 a 2 + 2 1 − 3 cos ( 2 θ ) R 2 b 2 ) + C

Simplifying a bit more:

⇒ U = − R G M e m ( 4 + 2 R 2 a 2 + 2 R 2 b 2 + 2 R 2 3 cos ( 2 θ ) ( a 2 − b 2 ) ) + C

Since θ is very small, I use the approximation: cos ( 2 θ ) ≈ 1 − 2 θ 2 . Hence,

⇒ U = − R G M e m ( k − R 2 3 ( a 2 − b 2 ) θ 2 ) + C

where k replaces the constant terms inside the parentheses.

The kinetic energy K of the system in CoM frame is

K = m ( a 2 + b 2 ) θ ˙ 2

Hence, the total energy E of the system at any instant is:

E = − R G M e m ( k ′ − R 2 3 ( a 2 − b 2 ) θ 2 ) + C + m ( a 2 + b 2 ) θ ˙ 2

Differentiating wrt time and setting the derivative to zero,

d t d E = R 3 3 G M e m ( a 2 − b 2 ) ( 2 θ θ ˙ ) + m ( a 2 + b 2 ) ( 2 θ ˙ θ ¨ ) = 0

Simplifying,

θ ¨ = − R 3 ( a 2 + b 2 ) 3 G M e ( a 2 − b 2 ) θ

Therefore, the time period of oscillation is:

T = 2 π 3 G M e ( a 2 − b 2 ) R 3 ( a 2 + b 2 ) = 2 π 3 G M e m ( η 2 − 1 ) R 3 ( η 2 + 1 )

As per the question, the time period is equal to 2 π R 3 / ( G M e ) .

⇒ 3 ( η 2 − 1 ) η 2 + 1 = 1

Solving for η , η = 2 ., which is the correct answer.

Is this enough or should I add something more?

Thanks a lot Josh!

Log in to reply

@Pranav Arora I didn't see this until now. I never got anywhere trying to go forward without the approximation (vs law of cosines like you do). Thanks a lot for posting it. I was perplexed when we were talking about this the first time.

One major typo in the third math line from the bottom, M t o t a l ω R o should be M t o t a l ω 2 R o . In the diagram, exchange the b cos θ for b sin θ and likewise.

Nice work!

Can you please tell a software or anything else you have used for the sketch.

Log in to reply

Hah, thanks. I just rigged the figure together in Keynote (http://www.apple.com/iwork/keynote/).

Hi Josh!

I know I should have asked this long before but I somehow forgot to.

I don't understand why the new distance is ( R 0 − a cos θ ) for the bottom most particle and similarly for others. Don't you need the distance from the centre of Earth? For that, we need to apply the law of cosines, no?

Many thanks! :)

Log in to reply

Hey Pranav, so I am taking R 0 to be the distance from the center of the satellite to the center of the Earth. I think we are in agreement on the distance we need to use. What do you think?

Log in to reply

Hello again! :)

I think my comment was misinterpreted or am I misinterpreting yours? I am very sorry if my post was not clear enough.

Yes, I understand that R 0 is the distance of central mass M to the centre of earth. What I don't understand is the distance of smaller point masses m from the centre of earth. I have the following picture in my mind: Image

To find the gravitational pull on m , we need to find l using the law of cosines but your solution or by Jatin and Dinh doesn't use it. Can you please clarify my doubt? Many thanks.

Log in to reply

@Pranav Arora – Ah, I see your point. Yes that's right and is the proper way to find the distance but at the scale that we're dealing with here, I would expect the difference in length between R − a cos θ and the outcome of the law of cosines to be really small and not change the answer much. I didn't actually check this but assumed it to be the case. How big do you find the difference in lengths to be?

btw, sorry for misspelling your name in the last post, it was my phone's fault ;-)

Log in to reply

@Josh Silverman – When I initially solved the problem, those distances you, Jatin and Dinh have used didn't work for me. My approach was calculating the energy of system at any instant and set its time derivative to zero. To calculate the gravitational potential energy, I used law of cosines to determine the distances from centre of earth and used some magical approximations before taking the time derivative. I did try the distances you used before the law of cosines but I couldn't reach the answer. Can you please clarify why the two methods (force and the energy) requires different distances?

Thank you very much. :)

Log in to reply

@Pranav Arora – Hmm, I can't think of a reason why we should require different distances. ;-(

Can you summarize the steps in your solution? Also, what is the answer you come up with using your approach?

Log in to reply

@Josh Silverman – The answer I come up with my approach is the same as yours.

I found the distances of point masses from the centre of earth when the satellite is rotated by an angle θ . Let r 1 be the distance of the bottom most point mass.

Then,

r 1 = r 1 2 = a 2 + R 2 − 2 a R cos θ ⇒ r 1 1 = R 1 + R 2 a 2 − R 2 a cos θ 1

(I calculate reciprocal of r 1 as gravitational potential energy is − G M m ( r 1 1 ) )

I then used the approximation,

1 − 2 x cos θ + x 2 1 ≈ 1 + x cos θ + 4 3 cos ( 2 θ ) + 1 x 2

Using the above approximation, I get:

r 1 1 = R 1 ( 1 + R a cos θ + 4 3 cos ( 2 θ ) + 1 R 2 a 2 ) .

Similarly, I calculated the other distances and used similar approximations. Calculating kinetic energy is easy and comes out to m ( a 2 + b 2 ) θ ˙ 2 .

I then added both the kinetic energy and potential energy to get the energy at any instant. Setting the time derivative to zero I was able to find the time period of oscillation.

Can you please tell me why I had to use these approximations while the distances you calculated worked fine with your method?

Many thanks!

Log in to reply

@Pranav Arora – just saw this. i will probably reply sometime this weekend.

Log in to reply

@Josh Silverman – Sure, please take your time. :)

@Pranav Arora – I've plotted the ratio of the approximate correction using R 0 = 1 0 6 a (how I did it in the problem) to the real correction (with the law of cosines). It seems they are indistinguishable:

image

image

Pranav, did you include the other kinetic energy terms:

2 1 m ω 2 [ ( R 0 − a cos θ ) 2 + ( R 0 + a cos θ ) 2 + … ] ?

Log in to reply

I should have been clear, I solved the problem in centre of mass frame. :3

Log in to reply

@Pranav Arora – I can definitely take a look at your solution and see what I can say about whether this difference in distances is required or not. But I don't think we will get very far if I keep guessing at your method ;-). Do you have a version of your solution available?

Log in to reply

@Josh Silverman – Sure. :)

I have posted it as a new comment. :)

Let d be the distance between M and center of earth (radius of orbit) , M e be the mass of earth , and w be the angular velocity of satellite. For sake of clarity, let us name the rods as A 1 , A 2 , B 1 and B 2 , where A 1 is the top rod and B 1 is the right rod.

Now, first it should be clear that the small oscillations would be relative to M , and w 2 = d 3 G M e

Let's rotate the system by a small angle θ in clockwise direction . In reference frame of M ,

We know that for x , , 1 , ( 1 + x ) n = 1 + n x , hence,

F A 1 = m w 2 ( d + a c o s θ ) − ( d + a c o s θ ) 2 G M e m = d 3 3 G M e m a c o s θ upwards

F A 2 = ( d − a c o s θ ) 2 G M e m − m w 2 ( d − a c o s θ ) = d 3 3 G M e m a cos θ downwards

F B 1 = m w 2 ( d + b s i n θ ) − ( d + b s i n θ ) 2 G M e m = d 3 3 G M e m b s i n θ upwards.

F B 2 = ( d − b s i n θ ) 2 G M e m − m w 2 ( d − b s i n θ ) = d 3 3 G M e m b s i n θ downwards.

Moment of inertia about axis passing through M and perpendicular to plane of oscillations = m a 2 + m a 2 + m b 2 + m b 2 = 2 m ( a 2 + b 2 )

Hence taking torque about M ,

F A ( 2 a s i n θ ) − F B ( 2 b c o s θ ) = 2 m ( a 2 + b 2 ) α

Now, approximate s i n θ = θ and c o s θ = 1 to get:

2 m ( a 2 + b 2 ) α = d 3 6 G M e m ( a 2 − b 2 )

Hence, time period of oscillation = 2 π 3 G M e ( η 2 − 1 ) d 3 ( η 2 + 1 ) .

Equate this to time period of satellite ,i.e. 2 π G M e d 3 to get η = 2

Note : α is the angular acceleration of the satellite.

@@~

First, we can easily calculate the angular velocity of the satellite: ω = R 0 3 G M 0 where M 0 is the mass of the Earth and R 0 is distance between M and the center of the Earth.

Now, we consider the reference frame associate with M, which travel with angular velocity ω ,

Suppose when the satellite rotate by a very small angle θ .

Therefore, the total force into each point mass m which associate with rod b is:

Δ F 1 = Δ ( m ω 2 R − R 2 G M 0 m )

= ( m ω 2 + R 0 3 2 G M 0 m ) Δ R = R 0 3 3 G M 0 m b θ .

The total force into each point mass m which associate with rod a is:

Δ F 2 = R 0 3 3 G M 0 m a .

The total torque into the system is: I θ ′ ′ = 2 Δ F 1 b − 2 Δ F 2 a θ .

2 m ( a 2 + b 2 ) θ ′ ′ = R 0 3 6 G M 0 m θ ( b 2 − a 2 ) .

θ ′ ′ + θ a 2 + b 2 3 ω 2 ( a 2 − b 2 ) = 0 .

In order to make the period of small oscillations of the satellite equals its orbital period, we have: a 2 + b 2 3 ( a 2 − b 2 ) = 1 , so b a = 2 ≈ 1 . 4 1 4 .