The Rich Get Richer

A bag initially contains one red ball and one blue ball. You select one of these balls at random and then place two balls of that same color back in the bag. For instance, if you drew a red ball, then you would put two red balls back into the bag so that the bag would contain two red balls and one blue bag. You repeat this until the bag contains 2016 balls. For the color that has the most balls present in the bag, what is the expected number of balls of this color? That is, after the bag contains 2016 balls, you open it and choose the color that has more balls (or choose either color in case of a tie); what is the expected number of balls of this color?

If the answer can be expressed as q p , where p and q are coprime positive integers, enter p + q as your answer.

The answer is 3048191.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

3 solutions

Moderator note:

Knowing that this problem is Polya's Urn allows us to start out with the surprising claim.

A more simple consideration via tree diagram resulted in the expression 4 3 n + 1 where n denotes the count of even samples. In our case n equals 2014 leading to an expected number 1 5 1 1 . 5 = 2 3 0 2 3 which means the solution is 3025.

Rem.: Indeed the difference between our expected numbers is approximately 0.25 which is less than one ball and therefore meaningless!

Log in to reply

If you were running a lottery paying out £1,000,000 to the lucky winner, but had only sold £1,200,000 of tickets, you would not regard an expected number of 1.25 winners as meaningless compared to an expected number of 1 winner. In the second case, you would probably make a profit. In the first case, you would probably go bankrupt. Certainly so if you did this every week!

Just because you are describing something that comes in integers, that does not mean that fractional parts of expectations aren't still very important! 2012 stats have the average number of children per family in the UK as 1.7; any demographic analysis (for example, projection of the need for primary school places in 2017) would be seriously adrift if we rounded 1.7 up to 2, and even worse if we rounded down to 1.

Log in to reply

Indeed you have always to consider the RELATIVE deviation that is in my case immensely less than in your interesting constructive far-fetched funny examples!

Log in to reply

@Andreas Wendler – You have said that a deviation of approximately 0.25 in the expectation of an integer-valued random variable is meaningless. I have given you two examples where such a deviation is anything but meaningless. Funny? Thank you. Far-fetched? I am not so sure.

You are claiming that the relative size of the error is relevant. I disagree. What we are talking about here is the fact that fractional factors in expectations of integer-valued random variables (which have a precise mathematical meaning) are important, as a matter of precision. If we choose to round those answers later, when interpreting them for Joe Public, that is another matter. Your calculation leading to 2 3 0 2 3 is approximate, but inaccurate.

Log in to reply

@Mark Hennings – When then for our problem surely sufficient because I think you are not able to deliver an empirical proof of your result! Have not heard anything of a tree diagram? Then you would realize that there is an equal distribution of the probabilities to get 1, 2, ..., 2015 balls of one color at the end fixing my result!

Log in to reply

@Andreas Wendler – Please read both my and Ivan's proof. We have both used the fact that the distribution of balls is uniform, and both obtained the correct answer. I suspect that you are calculating the expectation of the wring quantity. If you post yiur calculations, I can point out where you went wrong.

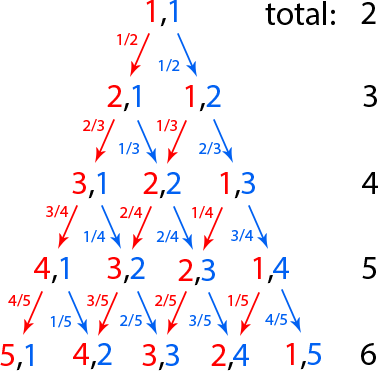

It's easy to notice that the probability of any particular sequence of draws resulting in r red balls and b blue balls in the bag is ( n − 1 ) ! ( r − 1 ) ! ( b − 1 ) ! (where n is the total number of balls) regardless of the order of the draws.

The number of paths leading to r red balls and b blue balls, which is the same as the total number of possible sequences of r − 1 red ball draws and b − 1 blue ball draws, is simply ( r − 1 ) ! ( b − 1 ) ! ( n − 2 ) ! .

It follows that the total probability of every sequence of draws leading to r red balls and b blue balls is the product of these:

( n − 1 ) ! ( r − 1 ) ! ( b − 1 ) ! × ( r − 1 ) ! ( b − 1 ) ! ( n − 2 ) ! = ( r − 1 ) ! ( b − 1 ) ! ( n − 1 ) ! ( r − 1 ) ! ( b − 1 ) ! ( n − 2 ) ! = n − 1 1

Knowing that the probability of each of the the 2015 outcomes resulting in 2016 total balls is uniformly distributed, calculating the expected value of the majority color is now very easy.

To account for the cases where the red ball is the majority: k = 1 0 0 9 ∑ 2 0 1 6 2 0 1 5 k

Similarly, to account for the blue ball majority cases: k = 1 0 0 9 ∑ 2 0 1 6 2 0 1 5 k

In the event of a tie: 2 0 1 5 1 0 0 8

Summing these:

2 0 1 5 1 0 0 8 + 2 k = 1 0 0 9 ∑ 2 0 1 6 2 0 1 5 k = 2 0 1 5 1 0 0 8 + 2 ∑ k = 1 0 0 9 2 0 1 6 k = 2 0 1 5 3 0 4 6 1 7 6

3 0 4 6 1 7 6 + 2 0 1 5 = 3 0 4 8 1 9 1

This is another case of Polya's urn; the probability that there are b + 1 blue balls after 2 n ball choices is 2 n + 1 1 for 0 ≤ b ≤ 2 n . If there are b + 1 blue balls after 2 n choices, there are m a x ( b + 1 , 2 n − b + 1 ) balls of whichever is the greater colour. Thus the expected number of the number of balls of the larger number after 2 n ball choices is M n = = = = 2 n + 1 1 b = 0 ∑ 2 n m a x ( b + 1 , 2 n − b + 1 ) 2 n + 1 1 ( b = 0 ∑ n − 1 ( 2 n − b + 1 ) + ( n + 1 ) + b = n + 1 ∑ 2 n ( b + 1 ) ) 2 n + 1 1 ( n + 1 + 2 b = n + 1 ∑ 2 n ( b + 1 ) ) = 2 n + 1 1 ( n + 1 + 2 n ( n + 1 ) + 2 b = 1 ∑ n b ) 2 n + 1 1 ( n + 1 + 3 n ( n + 1 ) ) = 2 n + 1 ( n + 1 ) ( 3 n + 1 ) With n = 1 0 0 7 we have M n = 2 0 1 5 3 0 4 6 1 7 6 , and so the answer is 3 0 4 8 1 9 1 .

Ah, yes, it's called Polya's urn. I didn't know its name.

Relevant wiki: Expected Value - Problem Solving

The answer is 2 0 1 5 3 0 4 6 1 7 6 , giving p + q = 3 0 4 8 1 9 1 .

We will prove the following surprising claim:

Claim : If the bag has n balls, then the probability that it has r red balls (and thus n − r blue balls) is exactly n − 1 1 , for all n ≥ 2 , 1 ≤ r ≤ n − 1 .

We will prove this claim by induction on n . For n = 2 , this is trivial (the bag starts with 1 red ball and 1 blue ball, so the probability that it has 1 red ball is 1 = 2 − 1 1 ).

Now, suppose we have proven the claim for n = n 0 , and we'd like to prove the claim for n = n 0 + 1 .

Fix r with 1 ≤ r ≤ n 0 . We want to compute the probability that when we have n 0 + 1 balls, we have r red balls. Consider the last ball added into the bag. There are two cases:

Case 1 : This ball was red, so the previous bag has r − 1 red balls out of n 0 balls. If r ≥ 2 , the probability of this happening is n 0 − 1 1 ⋅ n 0 r − 1 : the probability that we do have r − 1 red balls when we have n 0 balls (inductive hypothesis), multiplied by the actual probability of taking a red ball in this case. If r = 1 , the probability is zero since we cannot have no red balls in the bag (the original red ball must always remain in), but this can also be represented as n 0 − 1 1 ⋅ n 0 r − 1 because the second term is zero. So the probability that a red ball is taken to make our bag to have r red balls out of n 0 + 1 balls is n 0 − 1 1 ⋅ n 0 r − 1 .

Case 2 : This ball was blue, so the previous bag has r red balls (and thus n 0 − r blue balls) out of n 0 balls. This case is completely analogous with the above; the probability of this case happening is n 0 − 1 1 ⋅ n 0 n 0 − r .

In total, the probability that we have r red balls out of n 0 + 1 balls is simply the sum of the probabilities contributed by the two cases above; that is, n 0 − 1 1 ⋅ n 0 r − 1 + n 0 − 1 1 ⋅ n 0 n 0 − r = n 0 1 . This completes the proof.

Now that we have proven this, we can compute the expected value easily:

E ( number of majority balls ) = r = 1 ∑ 2 0 1 5 P ( $r$ red balls ) ⋅ number of majority balls = r = 1 ∑ 2 0 1 5 2 0 1 5 1 ⋅ max { r , 2 0 1 6 − r } = 2 0 1 5 1 ⋅ ( r = 1 ∑ 2 0 1 5 max { r , 2 0 1 6 − r } ) = 2 0 1 5 1 ⋅ ( r = 1 ∑ 1 0 0 7 ( 2 0 1 6 − r ) + r = 1 0 0 8 ∑ 2 0 1 5 r ) = 2 0 1 5 1 ⋅ ( r = 1 ∑ 1 0 0 7 ( 2 0 1 6 − r ) + r = 1 ∑ 1 0 0 8 ( 2 0 1 6 − r ) ) = 2 0 1 5 1 ⋅ ( 2 0 1 6 ⋅ 2 0 1 5 − ( 1 + 2 + … + 1 0 0 7 + 1 0 0 8 + 1 0 0 7 + … + 1 ) ) = 2 0 1 5 1 ⋅ ( 2 0 1 6 ⋅ 2 0 1 5 − 1 0 0 8 2 ) = 2 0 1 5 3 0 4 6 1 7 6

The second equality uses our result, together with the fact that the number of majority balls is simply the larger of r (number of red balls) and 2 0 1 6 − r (number of blue balls). The fourth equality uses the result that when r < 1 0 0 8 , the bigger one is 2 0 1 6 − r , and when r ≥ 1 0 0 8 , the bigger one is r . (Okay, they are equal when r = 1 0 0 8 , but we can choose either one.) The fifth equality performs the replacement r → 2 0 1 6 − r (this also reverses the order of summation). The sixth equality takes everything apart, setting the 2016's to the side. The seventh equality uses the (easily proven) fact 1 + 2 + … + n + ( n − 1 ) + … + 1 = n 2 .