The Strange and Secret Notes of Lovers

Guy Patrick was in love with Elmira von Brut, the only daughter of Sir John and Lady Georgina von Brut, in the stately House of von Brut.

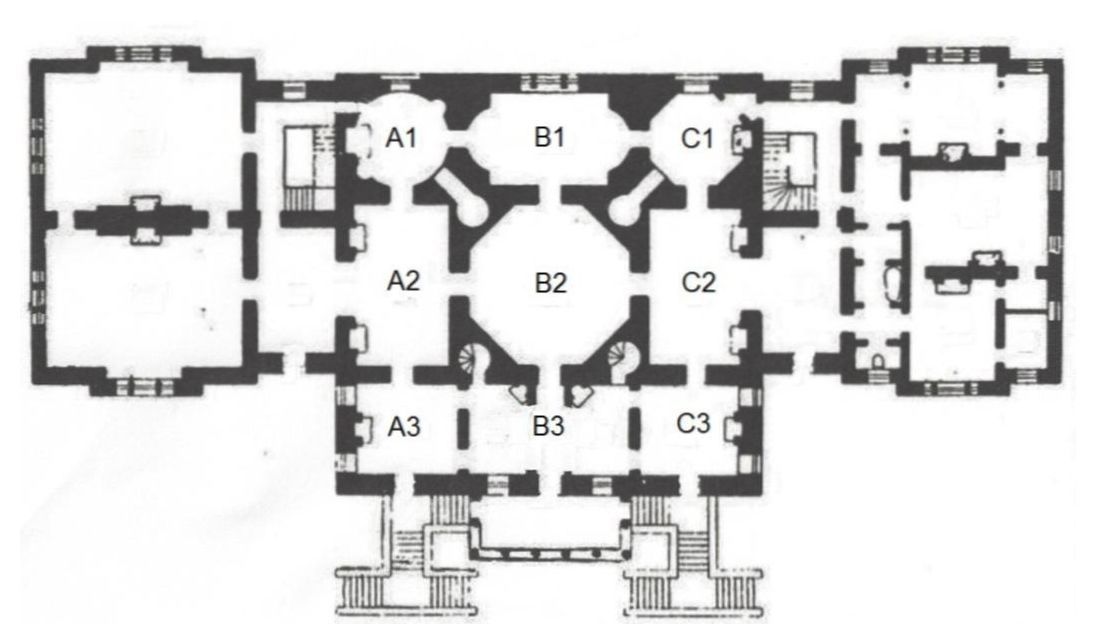

Distinguished generations of the von Brut family had passed through history, but Guy Patrick had the misfortune of being just a commoner. He was always a welcome guest, however, because of his penchant for scintillating conversation during the frequent times the Brut family had guests. Guy and Elmira kept their love secret by feigning intellectual but indifferent Platonism. But, meanwhile, Elmira regularly passed notes of love to Guy by leaving them at agreed secret drops in each of the rooms, all of the adjacent rooms having a door in common between them.

Because of the frequent presence of guests, and also because either Sir John or Lady Georgina was invariably in one or more of the rooms, Guy would only make a sweep of rooms at a time so as to not arouse suspicions, picking up the notes if they happened to be in any of the drops. He would sweep either rooms in a row, or rooms in a column, before he would try again on another night, and be satisfied with what he found, or did not find. After each night, Elmira would collect any notes left behind, and reseeded the rooms at the next opportunity.

Guy Patrick, while only a commoner, was an avid amateur scientist and mathematician, and had read the latest works of mathematicians of his age, Blaise Pascal, Christian Huygens, Abraham de Moivre, and Jacob Bernoulli whose book on probability theory, Ars Conjectandi , was just published posthumously. Flush with newfound ideas of probability theory, Guy carefully noted certain things about his successes with his room sweeps, namely,

1) Whenever he made a sweep of rooms in a row, either row or , it did not matter which row he chose; half of the time he would find exactly notes, one note in each of rooms out of which seemed to be at random, and the other half of the time he found nothing.

2) Whenever he made a sweep of rooms in a column, either column or , it did not matter which column he chose; he would always find exactly note.

Thus, the expected number of notes Guy would find in any room sweep was always .

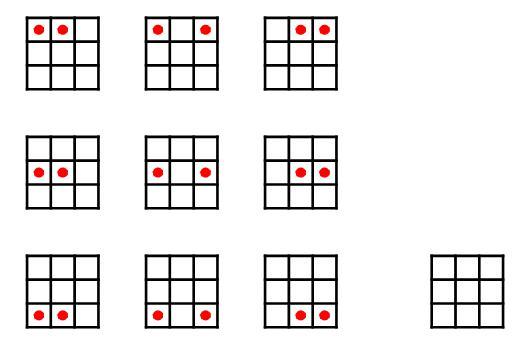

Following the ideas and examples shown in the works of these men, Guy carefully reasoned that, because of the fact he never found anything other than exactly note when making a sweep of rooms in a column, he proposed that what might be happening is that Elmira was always either leaving behind only notes, one each in a room, and only the rooms that were in a row, which was chosen at random, or she left behind nothing at all. He made himself a sketch of all possibilities as follows:

He hypothesized that each of the first cases was occurring with equal probability, while the last case where Elmira left behind nothing was occurring with a probability not necessarily equal to any of the other cases. He then did the math on this, figuring out what the probability of the last case of her leaving behind nothing had to be, in order to get a result that matched his experience and observation, which he did successfully.

He knew that Elmira was an extraordinary creature, as men who are in love often say about those they loved, but he was just enough of a mathematician to realize that what was happening was truly extraordinary. He couldn’t quite put his finger on it, but he felt as if he was glimpsing into a future when someday physicists would understand and explain this to him, but right now he found it hard to make any sense out of it, even though the mathematics of it was working out just fine.

What was the probability of Elmira leaving behind nothing? Give answer in decimal form.

Note:

This problem is asking for the probability of case

, assuming that

1) Guy Patrick is indeed finding the notes in the manner he has been experiencing, without either him or Elmira knowing ahead of time how, when, and where the notes would be left and be [or not be] found (other than the location of the secret drops);

2) the probabilities of the first cases are all the same, so that once the probability of case is computed, the probability of each of the first cases immediately follows, given that the total of the probabilities of all cases is

...in order to deliver results that Guy Patrick has been observing, whether or not such results are "possible" in "real life."

The answer is -0.5.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

This graphic shows what are the probabilities of each case occurring. If Guy makes a sweep of, say, Row 1, then the probability of finding 2 notes is

6 1 + 6 1 + 6 1 = 2 1

while the probability of finding nothing is

6 1 + 6 1 + 6 1 + 6 1 + 6 1 + 6 1 − 2 1 = 2 1

as he had found. Similarly, if Guy makes a sweep of, say, Column A, then the probability of finding 1 note is

6 1 + 6 1 + 6 1 + 6 1 + 6 1 + 6 1 = 1

while the probability of finding nothing is

6 1 + 6 1 + 6 1 − 2 1 = 0

as he had also found. Hence, the math works out, and predicts results that agrees with his personal experiences in collecting the notes. So, the probability of Elmira leaving behind nothing is − 2 1 = − 0 . 5