Two Gravitational Potentials

A bead of mass m is confined to a smooth wire in the shape of the curve y = x 2 .

The bead experiences a constant gravitational force of m g in the negative y direction, as well as a constant gravitational force of m g in the negative x direction.

The bead begins at rest at x = 1 . What is the time period of the bead's motion?

Details and Assumptions:

1)

m

=

1

2)

g

=

1

0

The answer is 3.283.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

2 solutions

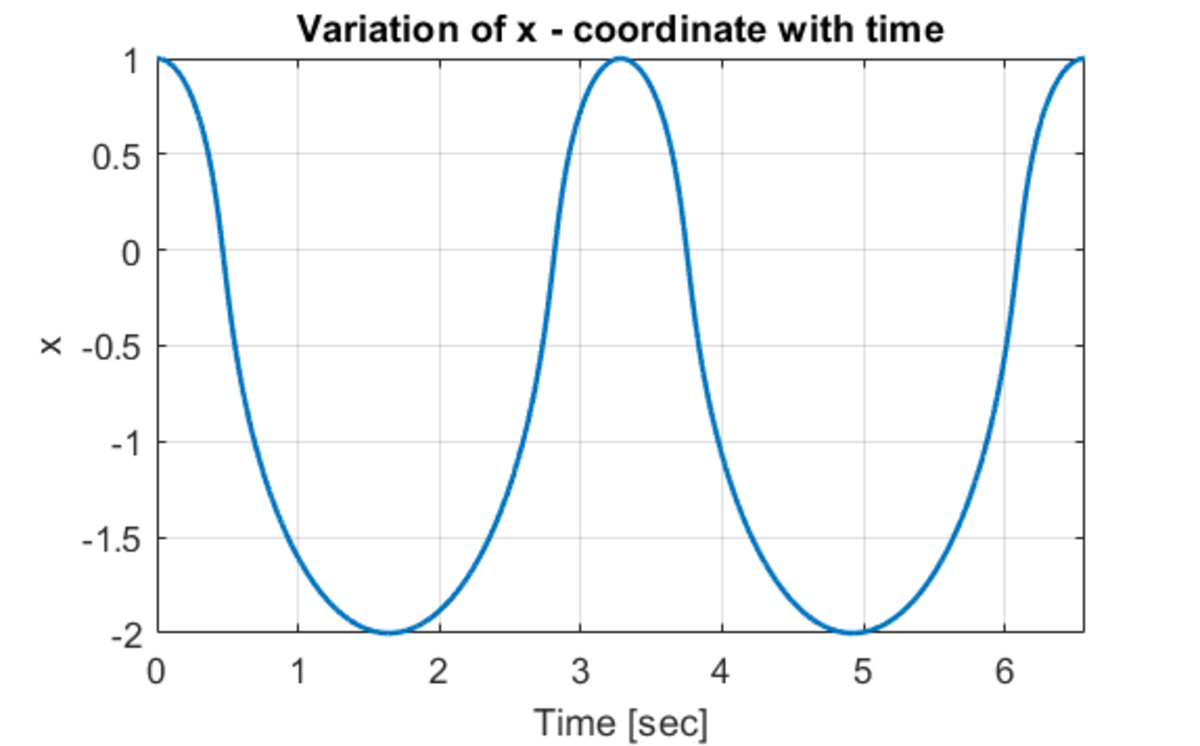

Very nice solution. I will supplement it with a graph that illustrates all your observations.

I got till the x_dot^2 equation and discarded thinking "this doesn't look like a periodic motion"..

Similar to the solution posted by @Mark Hennings . The only difference here is that I avoid deriving the equation of motion. Since there is no dissipative element present in the scenario, energy is conserved.

At ant instant of time t :

P E i n i t i a l + K E i n i t i a l = P E p r e s e n t + K E p r e s e n t

2 m g + 0 = m g ( x + x 2 ) + 2 1 m x ˙ 2 ( 1 + 4 x 2 ) 2 0 = 1 0 ( x + x 2 ) + 2 1 x ˙ 2 ( 1 + 4 x 2 )

Rearranging and observing that as t increases, x reduces, gives:

x ˙ = − 1 + 4 x 2 2 ( 2 0 − 1 0 ( x + x 2 ) ) = f ( x )

Observing that the derivative of x becomes zero at x = 1 and x = − 2 , we can say that the bead moves between these two points at half a time period.

Therefore:

2 T = ∫ − 2 1 f ( x ) d x ⟹ T = 3 . 2 8 2 5

The first integral of the equation of motion is, in cases such as this, a conservation of energy equation. Of course, your and my formula for x ˙ are the same.

Log in to reply

Yes, good point. For any single degree of freedom conservative system, the equation of motion is analytically integrable once. There could be framed as follows:

T + V = E

Where T and V are kinetic and potential energies respectively. If E = c o n s t a n t , The equation of motion is: d t d E = 0

Log in to reply

Although, I am not able to prove the above using Lagrangian mechanics. The goal of the proof is: Given an unforced conservative system, show using LM that the equation of motion is the total time derivative of the energy of the system equated to zero.

Any comments would be helpful.

Log in to reply

@Karan Chatrath – Look at Hamiltonian Mechanic s (and its derivation from Langrangian Mechanics). We can write the Hamiltonian, which is the energy of the system, in terms of generalised coordinates q 1 , q 2 , . . . , q n , generalised momenta p 1 , p 2 , . . , p n and time t , where p j = ∂ q ˙ j ∂ L Then, provided that ∂ t ∂ H = 0 , H is a constant of the motion.

In a 1D conservative system, the force on the particle is always − d x d V , where V is the potential. The equation of motion is thus 0 = m x ¨ + V ′ = d x d [ 2 1 m x ˙ 2 + V ] and so CoE of a first integral of the equation.

Log in to reply

@Mark Hennings – Thanks for the comment and for the suggestion.

The equation of motion of the particle is r ¨ = R − m g ( 1 1 ) where r is the position vector of the particle and R is the normal reaction from the wire. Now r = ( x 2 x ) , and hence r ¨ = ( 2 x 1 ) x ¨ + ( 2 0 ) ( x ˙ ) 2 Since the wire is smooth, R is normal to the tangent ( 2 x 1 ) of the curve. Thus, taking the scalar product with ( 2 x 1 ) , we see that m ( 1 + 4 x 2 ) x ¨ + 4 m x ( x ˙ ) 2 d x d [ 2 1 ( 1 + 4 x 2 ) ( x ˙ ) 2 + g ( x + x 2 ) ] 2 1 ( 1 + 4 x 2 ) ( x ˙ ) 2 ( x ˙ ) 2 = − m g ( 1 + 2 x ) = 0 = g ( 2 − x − x 2 ) = g ( 1 − x ) ( 2 + x ) = 1 + 4 x 2 2 g ( 1 − x ) ( 2 + x ) and so the particle oscillates between x = 1 and x = − 2 , and the period of oscillation is T = 2 ∫ − 2 1 2 g ( 1 − x ) ( 2 + x ) 1 + 4 x 2 d x = ∫ − 2 1 5 ( 1 − x ) ( 2 + x ) 1 + 4 x 2 d x = 3 . 2 8 2 5 2