Two Machine Dynamics

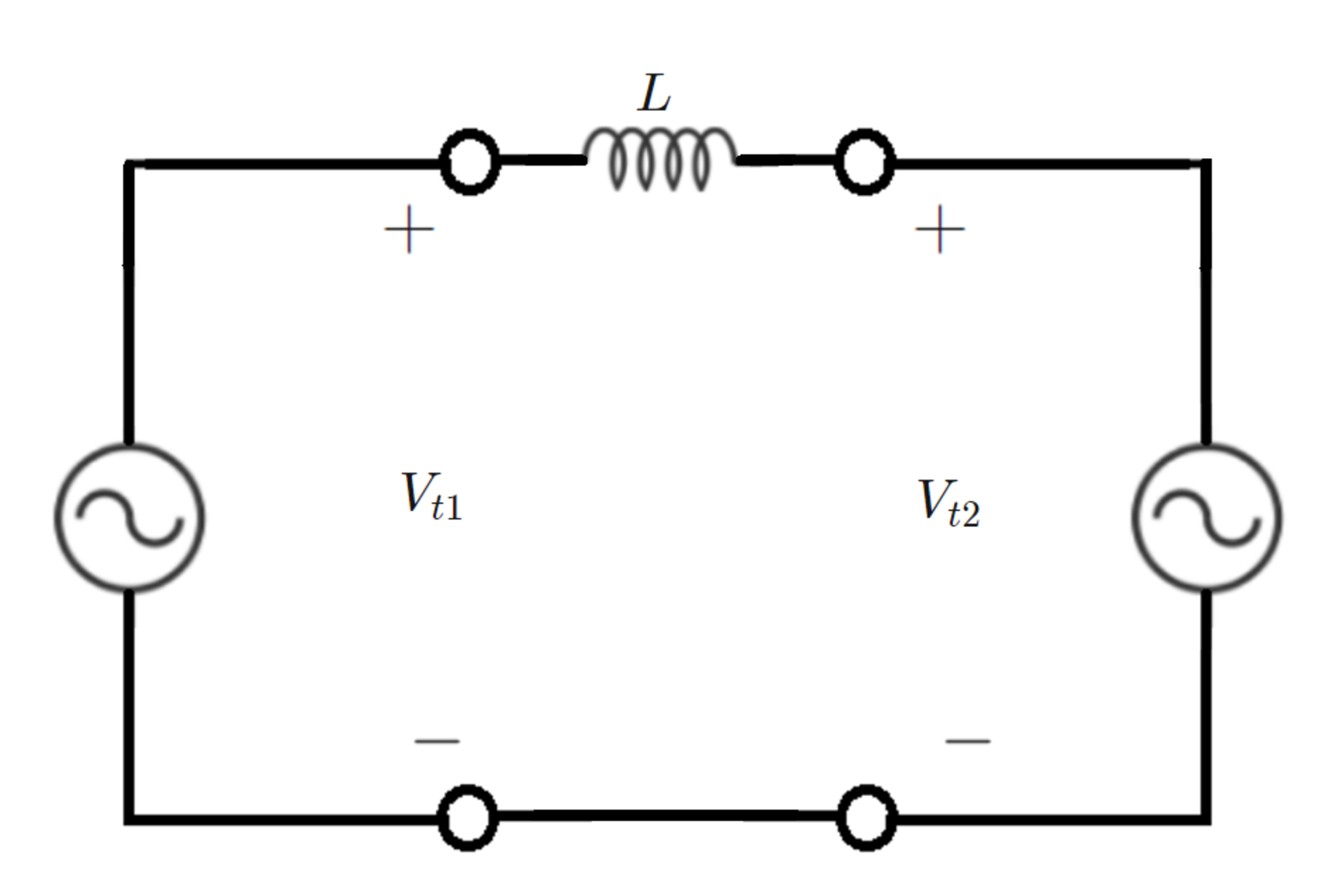

Two single-phase AC electric machines are connected to each other through an inductor, as shown in the diagram. Each machine has a moving rotor with a magnet, which induces a voltage at its stator terminals.

The machine model is as follows:

λ 1 = ω 0 V m cos θ 1 λ 2 = ω 0 V m cos θ 2 V t 1 = λ 1 ˙ V t 2 = λ 2 ˙ d t d ( 2 1 J θ 1 ˙ 2 ) = P M 1 − P E 1 d t d ( 2 1 J θ 2 ˙ 2 ) = P M 2 − P E 2

In the model, λ is the stator magnetic flux linkage as a function of rotor angular position θ . The terminal voltage V t is the time derivative of the stator flux linkage. The third pair of equations states that the rotor is gaining kinetic energy at a rate equal to the difference between the mechanical input power P M and the electrical output power P E (a statement of energy conservation). The parameter J is the machine inertia constant.

At time t = 0 , θ 1 = 9 π , θ 2 = 0 , θ ˙ 1 = ω 0 , and θ ˙ 2 = ω 0 . The current through the inductor is zero at this time.

Let θ ˙ 1 M be the maximum speed of Machine 1 over the time period 0 ≤ t ≤ 1 ?

What is θ ˙ 1 M − ω 0 ?

Bonus: Why does Machine 1 initially slow down while Machine 2 initially speeds up? What if θ 1 had initially been − 9 π ? Qualitatively, why do we see these oscillations?

Details and Assumptions (assume standard SI units):

1)

V

m

=

1

2

0

2

2)

ω

0

=

1

2

0

π

3)

J

=

0

.

0

1

4)

L

=

ω

0

1

5)

P

M

1

=

P

M

2

=

0

(prime movers are disconnected from both generators)

The answer is 16.56.

This section requires Javascript.

You are seeing this because something didn't load right. We suggest you, (a) try

refreshing the page, (b) enabling javascript if it is disabled on your browser and,

finally, (c)

loading the

non-javascript version of this page

. We're sorry about the hassle.

1 solution

Thanks for the detailed and comprehensive solution. My interpretation of the bonus question is as follows (taking a few liberties and applying AC steady state concepts to a dynamic system):

1)

Active power flows from leading angle to lagging angle

2)

Consequently, energy is transferred from Machine 1 to Machine 2 until the rotor angles are equal

3)

By the time the angle of Machine 2 catches up with that of Machine 1, Machine 2 is necessarily going faster

4)

That extra speed causes the Machine 2 angle to begin to exceed that of Machine 1

5)

When the Machine 2 angle exceeds that of Machine 1, energy begins to flow in the opposite direction

6)

Energy sloshes back and forth between the two machines in perpetuity, since there are no losses

It would be interesting to try to apply some control theory (of the sort you have been playing with), to damp out these oscillations

Log in to reply

Consider two control inputs which are like electric motors applying corrective torques to the rotors. Let these inputs be u 1 and u 2 and affect the system as such

⎣ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎡ x ˙ 1 x ˙ 2 x ˙ 3 x ˙ 4 x ˙ 5 ⎦ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎤ = ⎣ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎡ x 3 x 4 ( ω o J V m ) x 5 sin x 1 + u 1 − ( ω o J V m ) x 5 sin x 2 + u 2 ( ω o L V m ) ( x 4 sin x 2 − x 3 sin x 1 ) ⎦ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎤

Assume all the signals of the system can be measured and the measurements are noise-free. Then for a start, take:

u 1 = − ( ω o J V m ) x 5 sin x 1 + K ( ω o − x 3 ) n u 2 = ( ω o J V m ) x 5 sin x 2 + K ( ω o − x 4 ) n

Here, K must be a positive real number and n must be a positive odd integer. By using K and n as tuning parameters, observe how the amplitude of oscillations reduce. The oscillations do not damp out, however. This is an elementary approach. There are more sophisticated methods which I have not yet tried.

Log in to reply

This looks basically like what I would do as well. Have an extra control torque for the rotor which has the form − K ( θ ˙ − ω 0 )

When I apply the simple damping method, the speed oscillations gradually (and significantly) reduce, but do not completely disappear.

Log in to reply

@Steven Chase – Yes, I made the same observation. However, adding an additional term which is proportional to the derivative of the error is likely to induce some damping. I tried it and it works.

Thanks for the comments. I will give the control problem a bit of thought and share them when I have a result.

First and in my opinion, the most crucial part of this problem is the obtainment of the expressions for P E 1 and P E 2 .

Consider the equation of the circuit shown in the diagram. Consider the current to be flowing clockwise at an arbitrary instant of time. The equation is:

L d t d I = V t 1 − V t 2

Multiplying both sides by I d t and integrating from 0 to t gives us:

2 1 L I 2 = ∫ 0 t V t 1 I d t − ∫ 0 t V t 2 I d t = ∫ 0 t P E 1 d t + ∫ 0 t P E 2 d t

The way to interpret the above equation is that the electrical energy outputs of the generators are stored in the inductor. In other words,

P E 1 = V t 1 I

and

P E 2 = − V t 2 I

Having established this, the next step is to derive the governing differential equations of this electromechanical system. After simplifying and rearranging the given equations, the following are obtained:

θ ¨ 1 = ω o J V m I sin θ 1 … ( 1 ) θ ¨ 2 = − ω o J V m I sin θ 2 … ( 2 )

Replacing terms in the circuit equation gives:

d t d I = − ω o L V m ( sin θ 1 θ ˙ 1 − sin θ 2 θ ˙ 2 ) … ( 3 )

Now, this given system of equations is converted into a nonlinear state-space form as such:

Let: x 1 = θ 1 ; x 2 = θ 2 ; x 3 = θ ˙ 1 ; x 4 = θ ˙ 2 ; x 5 = I

Doing so gives us the following system description:

⎣ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎡ x ˙ 1 x ˙ 2 x ˙ 3 x ˙ 4 x ˙ 5 ⎦ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎤ = ⎣ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎡ x 3 x 4 ( ω o J V m ) x 5 sin x 1 − ( ω o J V m ) x 5 sin x 2 ( ω o L V m ) ( x 4 sin x 2 − x 3 sin x 1 ) ⎦ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎤ ⟹ x ˙ = f ( x )

Initial conditions are:

x ( 0 ) = ⎣ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎢ ⎡ π / 9 0 ω o ω o 0 ⎦ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎥ ⎤

Integrating the above using the explicit Euler method and evaluating the required expression using a computer program gives:

θ ˙ 1 M − ω o = 1 6 . 5 6 6 7

As for the bonus question:

The following plots should provide some insight:

It is seen that initially flows anticlockwise. Looking back at the angular acceleration equations, one can see that the value of the angular acceleration of the first machine is negative and that of the second machine is positive. Therefore, the speed of the first machine initially reduces while that of the second machine increases. If θ 1 ( 0 ) = − π / 9 and θ 2 ( 0 ) = 0 , the opposite would happen. This can again be understood by looking at the structure of the equations of the system. We see an oscillatory behavior as the flux associated with the two machines is of a periodic nature. As a result of that, the output voltages are oscillatory in nature and consequently, from the energy conservation principle, the rotational rate of both the machines are periodic. If there is more to this than meets the eye, please share your comments.